Focus on operational risks faced by Islamic banks

Mujtaba Khalid has a diversified range of experience spanning from government and private sector advisory, establishing effective governance frameworks, Islamic capital market products as well as conducting Islamic finance training and capacity-building programs.

He has worked for the UK-based Islamic Finance Council as a senior associate and his most recent role is to help establish an Islamic Finance Center at COMSATS CIIT – one of Pakistan’s leading universities along with other industry stakeholders.

Academically, Mujtaba Khalid’s undergraduate degree in Accounting and Finance is from the London School of Economics and M.Sc Investment Analysis from The University of Stirling. He also has three specialized Islamic finance qualifications namely; Islamic Banking and Finance Qualification from the State Bank of Pakistan (NIBAF), CIMA Islamic Finance Diploma and a Chartered Islamic Finance Professional (CIFP) from INCEIF.

Mujtaba Khalid’s research interests include formulating effective Islamic finance macro policy using tools such as social impact bonds, Shari’a impact investment methodology and creating a new methodology for rating Shari’a compliant investments.

Risk management has been a major focus in IBF, especially after Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB) was set up in 2002 in Kuala Lumpur. It has issued a number of regulatory standards, with an obvious focus on risk management. Consequently, a number of regulators have adopted these standards with minor changes to fit their national environments. State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) issued guidelines for risk management in Islamic banking institutions, which are primarily based on the IFSB Guiding Principles on Risk Management. Mujtaba Khalid summarises these guidelines before focusing on operational risk management in IBF.

As with other financial institutions, Islamic banking institutions (IBIs) are exposed to different categories of risk – financial and otherwise. A risk management framework is a set of guidelines and best practices that give practical effect of managing and mitigating the risks underlying the business objectives that IBIs may adopt.

Islamic banks should have a comprehensive risk management and reporting process, including appropriate board and senior management oversight, to identify, measure, monitor report and control relevant categories of risk. Risk management frameworks of IBIs shall also take into account appropriate steps to comply with Shari’a rules and principles and ensure the adequacy of relevant risk reporting.

IBIs should have a sound process for executing all elements of risk management, including – risk identification, measurement, mitigation, monitoring, reporting and control. This process requires the implementation of appropriate policies, limits; procedures and effective management information systems (MIS) for internal risk reporting and decision-making that are commensurate with the scope, complexity and nature of IBIs’ activities.

In addition to risk management, IBIs must also develop an Emergency and Contingency Plan in order to handle risks and complications which may arise from unforeseen events. The boxed texts throughout the article are copied from the guidelines issued by SBP. This article looks into different types of risk faced by an IBI, with a special focus on operational risk and its management in the context of Islamic banking. The next section summarises different risk categories, before looking into operational risk management in the following section.

Risks Faced By Islamic Banks

Equity Investment Risk Equity investment risk pertains to the management of risks inherent in the holding of equity instruments for investment purposes. Such instruments are based on the mudaraba and musharaka contracts. The capital invested through mudaraba and musharaka may be used to purchase shares in a publicly traded company or privately held equity or invested in a specific project, portfolio or through pooled investment vehicle. In the case of a specific project, IBIs may invest at different investment stages.

The equity investment risk may broadly be defined as the risk arising from entering into a partnership for the purpose of undertaking or participating in a particular financing or general business activity as described in the contract, and in which the provider of finance shares in the business risk. In evaluating the risk of an investment using the profit-sharing instruments of mudaraba, the risk profile of potential partners (mudarib) is a crucial consideration in the process of due diligence.

Such due diligence is essential to the fulfilment of the IBIs’ fiduciary responsibilities as an investor of deposits on a profit-sharing and loss-bearing basis (mudaraba). These risk profiles include the past record of the management team and quality of the business plan of, and human resources involved in, the proposed mudaraba activity.

Credit Risk

Credit risk is generally defined as the potential that the counter-party fails to meet its obligations in accordance with agreed terms. This definition is applicable to IBIs managing the financing exposures of receivables and leases (for example, murabaha, diminishing musharaka and ijara) and working capital financing transactions/projects (for example, Salam, istisna’ or mudaraba). IBIs need to manage credit risks inherent in their financings and investment portfolios relating to default, downgrading and concentration. Credit risk includes the risk arising in the settlement and clearing transactions.

IBIs should have in place a strategy for financing, using various instruments in compliance with Shari’a, whereby they recognise the potential credit exposures that may arise at different stages of the various financing agreement.

Liquidity Risk

Liquidity risk is the potential loss to an IBI arising from its inability to either meet obligations or to fund increases in unacceptable costs or losses. Liquidity risk generally occurs due to receivables and payables mismatch.

IBIs need to identify any future shortfalls in liquidity by constructing maturity ladders based on appropriate time bands. The IBIs may have their own criteria for classifying cash flows, including behavioural methods. As fiduciary agents, the IBIs are concerned with matching their investment policies with risk appetites of PLS deposit holders and shareholders.

If these investment policies are not consistent with the expectations and risk appetites of PLS deposit holders, the latter may withdraw their funds leading to a liquidity crisis for the IBIs. This applies particularly to PLS deposit holders.

Market Risk

Market risk is defined as the risk of losses in on- and off-balance sheet positions arising from movements in market prices, i.e., fluctuations in values in tradable, marketable or leas-able assets (including sukuk) and in off-balance sheet individual portfolios (for example restricted investment accounts). The risks relate to the current and future volatility of market values of specific assets (for example, the commodity price of a Salam asset, the market value of a sukuk, the market value of murabaha assets purchased to be delivered over a specific period) and of foreign exchange rates.

IBIs should define and set the objectives of, and criteria for, investments using profit sharing instruments, including the types of investment, tolerance for risk, expected returns and desired holding periods. IBIs should also keep under review, policies, procedures and an appropriate management structure for evaluating and managing the risks involved in the acquisition of, holding and exiting from profit sharing investments.

IBIs should establish policies and procedures defining eligible counter-parties (retail/consumer, corporate or sovereign), the nature of approved Shari’a Compliant financings and types of appropriate financing instruments. IBIs shall obtain sufficient information to permit a comprehensive assessment of the risk profile of the counter-party prior to the financing being granted.

IBIs should have in place a liquidity management framework (including reporting) taking into account separately and on an overall basis their liquidity exposures in respect of each category of current accounts, unrestricted and restricted investment accounts.

IBIs should have in place an appropriate framework for market risk management (including reporting) in respect of all assets held, including those that do not have a ready market and/or are exposed to high price volatility.

IBIs shall have in place appropriate mechanisms to safeguard the interests of all fund providers and stakeholders. Where PLS deposit holders’ funds are commingled with the IBIs’ own funds, the IBIs shall ensure that the bases for asset, revenue, expense and profit allocations are established, applied and reported in a manner consistent with the IBIs’ fiduciary responsibilities.

Operational Risk

The Bank of International Settlement (BIS) defines operational risk as the risk of loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people and systems or from external events. It includes legal risk, i.e., potential loss arising from lawsuits, which the bank must compensate its clients who suffered losses resulting from the operational lapses. Such risks could have an adverse impact on IBI’s market position, profitability and liquidity among others.

Operational Risks and Islamic Banks

Risk management for Islamic banks cannot be done by cutting and pasting risk management concepts and practices from conventional banks.

The savings and investments/financing/ trading contracts offered by Islamic banks have different transaction characteristics and a different risk profile than conventional banks. The uncertainties associated with Shari’a compliance leave banks exposed to fiduciary and reputational risks.

Shari’a compliance means adhering to the guidelines and rulings of Shari’a in all business and financial aspects.

The Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB), in its risk management standards, describes operational risk IBIs are exposed to as:

“IIFS are exposed to risks relating to Shari’a non-compliance and risks associated with the IIFSs’ fiduciary responsibilities towards different fund providers. These risks expose IIFS to fund providers’ withdrawals, loss of income or voiding of contracts leading to a diminished reputation or the limitation of business opportunities.”

Shari’a Non-Compliance Risk

Shari’a non-compliance risk is the risk that arises from IBIs’ failure to comply with the Shari’a rules and principles prescribed by Shari’a Advisor of an IBI. Shari’a compliance is critical to IBIs’ operations and such compliance requirements must permeate throughout the organisation and their products and activities. As a majority of the fund providers use Shari’a-compliant banking services as a matter of principle, their perception regarding IBIs’ compliance with Shari’a rules and principles is of great importance to sustainability of IBIs. In this regard, Shari’a compliance is considered as falling within a higher priority category in relation to other identified risks.

Islamic Financial Transactions and Shari’a Non- Compliance

There are at least six basic principles which are taken into consideration while executing any Islamic banking transaction. These principles differentiate a financial transaction from a riba/interest-based transaction to an Islamic banking transaction:

Sanctity of contract:

Before executing any Islamic banking transaction, the counterparties have to satisfy whether the transaction is halal (valid) in the eyes of Shari’a. This means that Islamic bank’s transaction must not be invalid or voidable. An invalid contract is a contract, which by virtue of its nature is invalid according to Shari’a rulings. Whereas a voidable contract is a contract, which by nature is valid, but some invalid components are inserted in the valid contract. Unless these invalid components are eliminated from the valid contract, the contract will remain voidable.

Risk sharing:

Islamic jurists have drawn two principles from the saying of Prophet Muhammad (SAW). These are “Alkhiraj Biddamaan” and “Alghunun Bilghurum”. Both the principles have similar meanings that no profit can be earned from an asset or a capital unless ownership risks have been taken by the earner of that profit. Thus in every Islamic banking transaction, the Islamic financial institution and/or its deposit holder take(s) the risk of ownership of the tangible asset, real services or capital before earning any profit therefrom.

- No riba/interest: Islamic banks cannot involve in riba/interest-related transactions. They cannot lend money to earn an additional amount on it. However as stated in point No. 2 above, it earns profit by taking risk of tangible assets, real services or capital and passes on this profit/loss to its deposit holders who also take the risk of their capital.

- Economic purpose/activity: Every Islamic banking transaction has certain economic purpose/activity. Further, Islamic banking transactions are backed by tangible assets or real services.

- Fairness: Islamic banking inculcates fairness through its operations. Transactions based on dubious terms and conditions cannot become part of Islamic banking. All the terms and conditions embedded in the transactions are properly disclosed in the contract/agreement.

- No invalid subject matter: While executing an Islamic banking transaction, it is ensured that no invalid subject matter or activity is financed by the Islamic financial transaction. Some subject matter or activities may be allowed by the law of the land but if the same are not allowed by Shari’a, these cannot be financed by an Islamic bank.

Any transaction that does not adhere to the aforementioned rules, would be considered Shari’a non-compliant and thus be invalid.

Internal Shari’a Control Mechanisms for Islamic Banking Contracts

In this section, we will be looking at Islamic contracts structured for the banks operations and the internal Shari’a control mechanisms that need to be followed.

For deposits, we will look at the mudaraba contracts, for leasing the ijara contract will be examined and for financing, a partnership based musharaka contract will be observed.

Internal Shari’a Control Mechanism for Mudaraba Deposits

Mudarabah is a profit-sharing contract under which, the rabb al-mal (capital provider) provides capital to the mudarib (entrepreneur/business manager) to invest in a business activity. The returns from the investments are then shared between the capital provider and the business manager on a pre-agreed ratio. In mudaraba-based deposits in Islamic banking, the depositors provide capital while the banks manages the business.

Shari’a Control Mechanism in this case should ensure:

- No fixed return is committed to high-value depositors

- No extra privilege is given to high-value current account holders

- The actual status of the deposit is mentioned in the account opening document and in the correspondence with the customer

- The profit earned during the period has been distributed according to an approved distribution methodology

- Profit distribution sheets of each term has been approved by the Shari’a advisor

- The profit is allocated using the concept of daily product and weight-age system

- AAOIFI standards require Islamic banks to present the depositor’s fund as a form of equity.

- Restricted investment account holders have to be shown in an off-balance sheet statement

Internal Shari’a Control Mechanism for Ijara Financing Ijara is the lease of a non-consumable asset. The difference between an ijara contract and a conventional lease is that the ownership and all associated risks remain with the lessor till the end of the ijara term.

Shari’a Control Mechanism in this case should ensure:

- The bank documented the transaction properly.

- The asset is specified and known – proper asset description and date of delivery must be mentioned in the relevant document.

- Total cost of the asset must be determined at the time of the execution of the lease agreement and will include all ownership related costs e.g. takaful (insurance) duties, taxes, transportation.

- The ijara period is known – Specified date of each monthly rental becoming due must be clearly mentioned in the rental schedule.

- A proper mechanism is agreed upon in case need to change rental rate.

The ijara is concluded correctly and the ownership is transferred to the customer (in case of ijara wa iqtina’).

- The responsibility of risk is clearly known to both the bank and customer.

- The nature of rentals is clearly known, i.e., in advance or in arrears.

- The rental payment starts after the delivery of the asset NOT from the contract date – in case the asset requires some time for installation, the rentals will start after the asset is in a useable condition.

- Rentals can be fixed or variable – in case of variable rate rental, the rentals for the first period must be fixed at the time of execution of the ijara agreement and will chang according to a known formula.

- The asset is transferred (by means of gift or sale) through a separate contract at the end of the lease term (in case of ijara wa iqtina’) Internal Shari’a Control Mechanism for Diminishing Musharaka Financing

Diminishing musharaka is a composite product that comprises shirka (joint ownership), ijara rental and bai’ (sale). Rules of the mentioned contracts need to be ensured for this product.

Most processes are the same as in the ijara contract. Shari’a Control Mechanism for this should ensure:

- The steps of implementation should be defined in advance, i.e., shirka first then ijara and then sale

- This arrangement should not be used for cash financing

- In a sale of a lease back transaction, the sale of units will start after completion of one year to avoid buy-back arrangement

- There must be a mechanism to deal with early maturity and balloon payments

Back and Middle Office Operations and Risk Management

The risk management functions relating to treasury operations are mainly performed by the middle office. The concept of middle-office has recently been introduced so as to independently monitor, measure and analyses risks inherent in treasury operations of banks. Besides, the unit also prepares reports for the information of senior management as well as a bank’s Asset and Liability Management Committee (ALCO). Basically the middle office performs risk review function of day-to-day activities. Being a highly specialised function, it should be staffed by people who have relevant expertise and knowledge.

A middle-office setup, independent of the treasury unit, could act as a risk monitoring and control entity reporting directly to top management.

Keeping tabs on the Value-at-Risk (VaR), ensuring adherence to external and internal guidelines and evolving risk monitoring systems would be some responsibilities of such a setup. The methodology of analysis and reporting may vary from bank to bank depending on their degree of sophistication and exposure to market risks. These same criteria should govern the reporting requirements demanded of the middle-office; which may vary from simple gap analysis to computerized VaR modeling. Middle-office staff may prepare forecasts (simulations) showing the effects of various possible changes in market conditions related to risk exposures. Banks using VaR or modeling methodologies should ensure that its results are consistent.

Regular information flow from the Head of Treasury to the Head of Middle Office department is expected in discharging these responsibilities. Investment in information technology (IT) as tools for decision-making allows banks to respond in real-time to operational needs. However the ability to monitor and respond manually in the absence of IT tools is still required.

The roles of an effective middle-office operation are to ensure:

- A systematic approach to risk control for all products

- Understanding of the necessary legal, documentary and regulatory frameworks

- Effective interaction with the front office and other departments

- The preparation and support for the introduction of new products

- The implementation of effective accounting, reporting and MIS

- Comparing the “best practices” of middle- office operations

Risk assessment should cover all risks facing the bank and the consolidated banking organisation (that is, Shari’a risk, country and transfer risk, market risk, interest rate risk, liquidity risk, operational risk, legal risk and reputational risk). Financial controls may need to be revised to appropriately address any new or previously uncontrolled risks. Areas of potential conflicts of interest should be identified, minimised, and subject to careful, independent monitoring. Control activities should include: top level reviews; appropriate activity controls for different departments or divisions; physical controls; checking for compliance with exposure limits and follow-up on non-compliance; a system of approvals and authorisations; and, a system of verification and reconciliation.

There should be an effective and comprehensive internal audit carried out by operationally independent, appropriately trained and competent staff. These systems, including those that hold and use data in an electronic form, must be secure, monitored independently and supported by adequate contingency arrangements. The internal audit function, should report directly to the board of directors or its audit committee, and to senior management. Deficiencies, whether identified by business line, internal audit, or other control personnel, should be reported in a timely manner to the appropriate management level and addressed promptly. Material internal control deficiencies should be reported to senior management and the board of directors.

The Way Forward

The challenge going forward is for Islamic banks to establish a cultural mindset and operating framework that embed balance sheet risk – something beyond the regulatory requirements set out under Basel III.

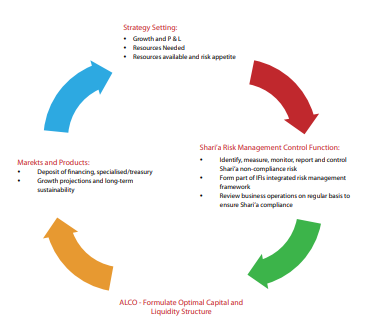

As regulations become more stringent and the market becomes saturated, banks need to enforce an inclusive risk management ensuring effective teamwork. The diagram below gives a brief illustration of what might be needed for Islamic banks to be more effective.

As more complex deals are being executed and more complicated products are being developed, if any institution, inside or outside the IFI, deserves scrutiny, it is the Shari’a scholars. Therefore, apart from a Shari’a audit to check compliance with the Shari’a governance frameworks provided by the Shari’a board, a Fatwa Audit is also proposed in countries where no centralised Shari’a supervisory board is instituted. This would be an independent audit carried out to determine what ijtihad was used by the Shari’a scholar or board in deeming a deal, product or transaction as Shari’a compliant. This can be a revolutionary step in tackling the creeping cynicism about Islamic finance among Muslims.

Being suitably qualified requires both a minimum level of knowledge and skill as an entry criterion, and also the need to have ongoing training. Shari’a scholars working as advisors to an IFI need also to consider the risks of litigation over the advice they provide as increasing litigation activity related to Islamic finance is being seen in courts. Initiatives in the Islamic finance industry specifically addressing the issue of competence include “fit and proper” criteria set by industry regulators. However, it is preferred that central Shari’a boards be constituted in all the countries where IBF is significant. This will ensure that no tension crops up between Shari’a scholars and other stakeholders involved in IBF.

Consumer Relations

One aspect that is lagging is an effective consumer relations policy, focusing on aspects such as anticipating a change in consumer needs and how they will defer in the next 5 years, how to respond to such changes and how to target new consumer groups.

Commercial transactions include an element of trust. Research shows that the quality of customer-facing employees and the ease of doing day-to-day business are the most important elements in building or reinforcing trust. IFIs should create service excellence on top of operational excellence.

This requires proactive relationship management: maintaining a dialogue with customers, creating awareness about Islamic finance among consumer groups through conferences and education programmes, acting in their best interests and coming up with solutions for personal financial situations.

Islamic banks should also bear in mind that, as mentioned above, most of the Muslim demographic is young and their consumer base would mostly consist of Gen-Y individuals. These individuals tend to be higher educated and critical; they often have above-average incomes and are extensive users of technology. Therefore effective use of technology in terms of products which are not only easy to understand but also reduce effort and the use of social media for marketing campaigns should be employed effectively.

In this respect, the

State Bank of Pakistan has just released a comprehensive study called KAP Report that, apart from quantifying demand for Islamic banking in the country, highlights knowledge, attitude and practices of Islamic banking in Pakistan. There is a need that all banking and financial regulators to conduct such studies to find out supply-demand gaps and how to fill these. This will be an excellent step towards identifying Islamic banking-specific risks, with a view to managing them to protect theinterests of all the stakeholders.