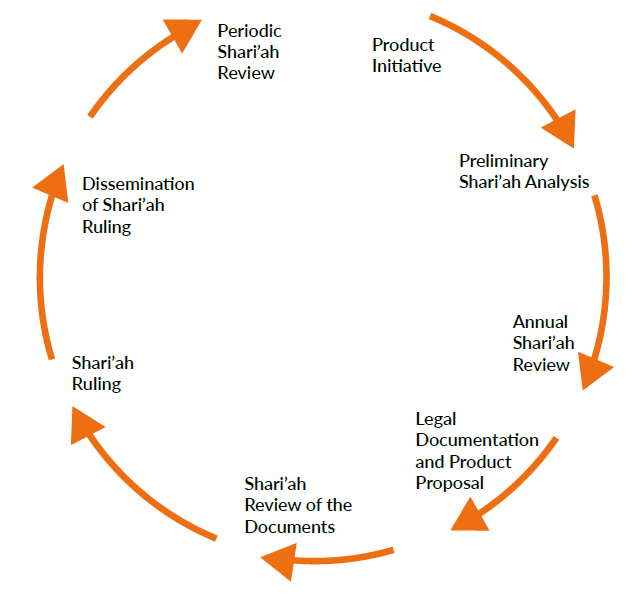

The emergence of Islamic finance has introduced a new discipline known as “Shariah advisory services” (SAC). SAC adds a unique value proposition of religious law in the area of commercial life, where secularism rules almost unquestioned throughout the rest of the world. This phenomenon has emerged as a regulatory requirement to ensure Islamicity of Islamic financial institutions (IFIs) by establishing an independent Shari’ah Board (SB). According to AAOIFI, “Shari’ah board is entrusted with the duty of directing, reviewing and supervising the activities of the IFIs to ensure that they comply with Shari’ah principles”. The following diagram depicts the cycle of SB involvement in the business of an IFI.

One of the major responsibilities of SB is to issue a Shari’ah certification (fatwa) endorsing Shari’ah compliance of the products offered by the institution. Shari’ah scholars (SB members) pronounce the resolution through a collective ijtihad — a systematic logical approach adopted to apply legal ruling to a financial matter based on their interpretation of Shari’ah sources. From a juristical perspective, this is called “tanqihul manat”. According to Sheikh Taqi Usmani, a leading Islamic finance scholar, the process of tanqihul manat requires a Shari’ah scholar to get the “right description” (tassawur al-mas’alah) by understanding financial nature and business model of the product and, then to apply the relevant Shari’ah ruling (al-ttakyif al-shari).

The exercise of tanqihul manat is in fact an important component of Shari’ah advisory services provided to IFIs by Shari’ah scholars, which simply can be termed as “Shari’ah decision making”. Scientific research proved that there are various psychological traps, which significantly influence decision-making. This article highlights only those traps that potentially lead to debacles in Shari’ah decision-making, namely.

- the framing trap, (2) the status-quo trap, (3) the anchoring trap and (4) the confirming-evidence trap, along with antidots tips.

THE FRAMING TRAP

The first logical move in tanqihul manat is known in business management science as “framing the problem”. It is like a frame around a picture that separates it from the other objects in the room. In Shari’ah decision-making, framing creates a mental border that encloses a particular aspect of a situation to outline the key elements of it for in-depth understanding. A mental frame enables the Shari’ah scholars to navigate the complex nature of a financial product, so they can avoid solving the wrong problem or solving the right problem in the wrong way.

Since the majority of SB members (Shari’ah advisors) come from Shari’ah background, they typically rely on the information presented to them by the management of an IFI (i.e. business and product development unit) as they normally do not possess practical exposure to analyse directly a complicated product. Therefore, the way a product is defined to them by the management actually shapes the potential Shari’ah solution that SB members select (of course with some exceptional Shari’ah minds who have developed throughout the years a phenomenal comprehension of financial markets).

A substantial amount of studies found that “framing” significantly impacts outcome of a decision. The framing effect is an example of cognitive bias, in which people react to a particular choice in different ways depending on how it is presented e.g. as a loss or a gain, positive or negative.4 Similarly, there are evidences suggesting that framing influences Shari’ah decision in Islamic finance industry depending on the manner in which a financial matter is presented before the SB.

A famous example of the framing trap could be a fatwa endorsing conventional insurance as attributed to a famous Egyptian Scholar Muhamad Abdahu. A French man explained to him that insurance is like a mudarabah contract where one party provides capital and the other manages the fund. Later, he asked Muhamad Abdahu about its Shari’ah status. Muhammad Abdahu considered it a Shari’ah-compliant product based on the information presented to him. This was in reality “mids-framing” of the product.

Another latest example in Islamic finance would be the case of Islamic total return swap proposed by a multinational bank in 2007 and was approved by some Shari’ah scholars. The proposed product was claimed to be a Shari’ah-compliant version of the conventional total return swap (TRS), which had been christened as the “wa’d” (unilateral promise) – based total return swap. The objective was to use non-compliant assets and their performance to swap its returns into a so-called Shari’ah-compliant investment portfolio.

The product was presented to Shari’ah scholars in a way reflecting that the performance of non-halal fund is just used as a benchmark index for the Islamic investment fund, resembling the interest-based pricing mechanism (LIBOR) in Islamic banking products. However, its legality was heavily criticised by other scholars on the ground that wa’d is used as a mere stratagem to halalize a prohibited income. The analogy (qiyas) between the use of LIBOR for pricing and the use of the performance of non-Shari’ah-compliant assets for pricing is both inaccurate and misleading. The only similarity is that both are used for pricing. LIBOR is used to indicate the return, while the other is used to deliver the return.

Sheikh Yuosuf DeLorenzo categorically considered this Shari’ah decision as an unfortunate one (due to mis-framing):

“It is an unfortunate shortcoming on the part of the Shariah board in this transaction that it has failed to consider the context of the offering. It is an even greater shortcoming when it fails to consider the consequences the product will have for the entire industry. When it is clear that a product cannot be offered in its own form or, in other words, when it cannot be offered directly, but must be offered by means of a stratagem that is basically a derivative like a swap, red warning flags should go up. In such situations, the Shariah Board must pay careful attention to the circumstances of the offering. If the circumstances can be found to justify such a product, then it may be possible to grant approval. If not, however, approval must be withheld. In the case of promised returns from a referenced basket of assets, the assets must be Shariah compliant in order for the returns to be Shariah compliant. It really cannot be otherwise.”

To avoid such incidences, Shari’ah scholars shouldn’t automatically accept the initial frame formulated by one of SB members or the management. Rather he should always try to reframe the problem in various natural ways. Sheikh Taqi Usmani accentuated that a Shari’ah scholar shall get a deep understanding of the concerned case before issuing a fatwa:

Sometimes the fatwa seeker–due to his limited knowledge (of Shari’ah)– cannot explain features that determine Shari’ah ruling (of the case enquired). In such scenarios, the scholar (mufti) shall try to obtain the relevant information by other means. This happens–mostly– in commercial affairs-related questions in which the fatwa seeker presents a case according to his understanding and ignores the important aspects (that impacts Shari’ah ruling). While in some instances, the fatwa seeker deliberately misrepresents (mis-frames) the matter (to manipulate its Shari’h ruling).

…Therefore, Imam Muhammad– a famous Muslim jurist– used to visit markets to understand nature of the business nature and the prevailing commercial trends.

THE STATUS-QUO TRAP

Status quo trap is an emotional bias and a preference for the current state of affairs. Psychologically, human brain considers a prevailing practice as a reference point and perceives other alternatives that vary from that baseline as inferior, hence undesirable.8 This trap affects decision-making eloquently as it underpins that the current practice is based objectively on a rationale. Therefore, whenever a new product is introduced there is a great tendency of rejection in the market.

In the case of Islamic finance, the status-quo influences Shari’ah decision-making from two aspects: management and scholarly reputation. It has been argued that the sin of innovation (thinking out of the box) tends to be punished much more severely than sins of replicating conventional products. The management often displays a strong bias toward a “novel” proposal since it perpetuates the ‘status-quo’ of existing conventional financial system that still—unfortunately—serves as a baseline for Islamic banking industry. For example, in 2014, Bank Negara Malaysia introduced mudarabah, musharakah and waka lah-based investment account policy to portray the true spirit of Islamic investment. Nevertheless, instead of adopting this new model, IFIs resorted back to tawarruq-based products.

On the other hand, it is also observed that if a product is approved by famous Shari’ah scholars, it becomes often a challenge for junior Shari’ah scholars to question it or even to suggest another alternative due to the well-endowed reputation of those who endorsed it. To some extent, the status quo may be considered—depending on the case— a viable option. However, adhering to it out of fear will limit Shari’ah advisory options, and ultimately will compromise effective decision-making.

To overcome this challenge, all other options should be carefully analysed. Exaggerating the effort or cost involved in switching from the status quo should be avoided. As far as questioning the opinion of senior Shari’ah scholars is concerned, the rule of thumb in Islamic discourse is to examine validity, authenticity and suitability of the underlying Shari’ah justification in the light of Islamic jurisprudence. This principle is exemplified by the evolution of Islamic jurisprudence into different school of thoughts, proving how constructive criticism has been playing a productive role throughout Islamic civilisation. An academic criticism shall not constitute by any means a discredit.

THE ANCHORING TRAP

Anchoring in psychology refers to the common human tendency of giving disproportionate weight to the first information he or she receives. During decision-making, an initial impression, estimate or idea thwarts subsequent thoughts and judgments, like an anchor that prevents the boats from moving away. For example, the initial price offered for a used car, sets an arbitrary focal point (anchor) for all following discussions. Prices discussed in negotiations that are lower than the anchor may seem reasonable, perhaps even cheap to the buyer, even if said prices are still relatively higher than the actual market value of the car.

In Shari’ah decision-making, a common anchor could be the first proposal presented either by the management or a member of the SB. For instance, when an IFI intends to replicate a conventional product, its first Shari’ah-compliant structure (al-ttakyif al-fiqhi) proposed during a brainstorming session may serve as an axis around which the subsequent discussion will revolve. One good example is the excessive use of tawarruq, which was initially suggested for personal financing in dire need cases. Nonetheless, since last two decades tawarruq has become the ideal baseline for both assets and liabilities sides products offered by IFIs.

Due to its anchoring effect, it paved the way for reverse financial engineering that led to stagnancy and lack of innovation in Islamic finance. A prominent Islamic economist Najatullah Siddiqi demonstrated through macroeconomic analysis that the harmful consequences of tawarruq are much greater than the benefits generally cited by its advocates. He further articulates:

The market has enthusiastically welcomed this development (tawarruq) mainly because it takes us back to familiar grounds long trodden under conventional finance. As a result, several scholars who approved tawarruq in the first instance are raising their voices against its indiscriminate widespread use. But profit maximizers have rarely been amenable to moral exhortations.

It is recommended to try using alternative starting points and approaches rather than sticking with the first line of thought that occurs. A scholar should be open-minded with the capability to think about the problem independently before consulting others in order to avoid becoming anchored by their ideas. He should be vigilant to avoid anchoring by advisers, consultants and others from whom he solicits information and counsel. He should share with them as little as possible about his own ideas, estimates, and tentative decisions as revealing too much may result in his preconceptions simply coming back to him.

THE CONFIRMING-EVIDENCE TRAP

Confirmation bias is the tendency to “search for or favour evidence and information that confirms one’s preexisting beliefs or hypotheses”. Research shows that decision-makers sometimes seek out information that supports their prevailing instinct or point of view, while avoiding information that contradicts it. This trap affects the individual to halt gathering information when the evidence gathered confirms the views (prejudices) one would like to be true. The source of confirmation bias lies deep within human psyches that disconfirmation is unquestionably superior to confirmatory reasoning.

In Shari’ah decision-making, a common confirming bias occurs when a scholar seeks juristical evidences in classical literature (al-juzyat al-fiqhiyyah) to validate his position regarding a contemporary case. Bai’ al-inah (sale of an asset with its subsequent repurchase on a deferred payment basis) – a common Islamic financing product in South Asia but divisive in other jurisdictions – would be a good example to illustrate the confirming-evidence trap. Although Its permissibility is narrated from Imam Al-Shafi’i (founder of Shafi’i school of thought), but he referred to it as an unorganised sale that takes place occasionally without prior arrangement. Yet, this reference was taken by some IFIs to legalise a buy-back sale in an organised manner to offer a commercial financial product. This practice has created a growing frustration among scholars and proponents of Islamic economics due to the failure of Islamic finance in addressing the real economic and ethical issues beyond the legal realm of Shari’ah compliance.

Such a cheery-picking legalism not only undermines the true spirit of Islamic law (maqasid al-Shari’ah), but also deviates from the multi-dimensional aspects of Islamic finance at both macro and micro level. A famous Hanafi jurist Ibn Abidin rightly pointed out that a Shari’ah ruling in classical feqhi texts is usually based on the cultural norms of that particular period, which no longer can be prevalent. Consequently, some opinions of past jurists cannot be applicable to contemporary cases. After mentioning various examples of cultural trends that have changed with the passage of time, he concluded: “these are clear evidences affirming that a mufti (scholar) shall not confine himself (in making a Shari’ah decision) to what is written in classical books without taking into consideration the contemporary practices. Otherwise, the harm of such a Shari’ah decision will be more than its benefits.

To circumvent confirming bias, a scholar should examine evidences with equal rigour avoiding the tendency to accept confirming evidence without question. One of SB members may play devil’s advocate to argue against the contemplating decision. All possible juristic solutions should be explored before drawing at a Shari’ah resolution. In seeking the advice of other experts, leading questions that invite confirming evidence should not be asked. It is advisable for SB member to not surround himself with a yes-man who always seems to support his point of view.

CONCLUSION

Psychologists have identified a series of manipulative flaws hardwired into human thinking process, which we often fail to recognise them during decision-making. Shari’ah decision is apparently not an exception. By analysing the above facts, it can be concluded that these traps together point towards two key findings. First, an unfortunate Shari’ah decision might be the result of the partial information received by SB members and their subsequent limited perspectives. Such a decision will not only undermine legality of the product enquired but might also trigger reputational risk for the industry. To provide profound Shari’ah advisory services that reflect the multi-dimensional aspects of Islamic finance, the SB should deal with accurate information exploring issues from multiple perspectives.

Second, most of these decision-making traps are correlated. Falling into one trap often leads to become prey of other traps as well. Avoiding these traps largely depends on how the SB members interact with each other during a decision-making process. Furthermore, we are always susceptible to these traps in the future despite having a successful track record in the past due to the different nature of decisions and circumstances. Therefore, Shari’ah scholars who are the source of confidence in Islamic financial industry should critically evaluate the situations confronting them to bypass the traps.

Ehsanullah Agha is a PhD Scholar of Islamic finance at International Islamic University Malaysia and he is currently associated with Habib Metro Bank-Sirat Pakistan.