Islamic finance, after four decades of progress and development, is no longer “swimming against the tide”. The founder of one of the largest Islamic banks in the world, Sheikh Ahmed Al-Yasin (Rahimahum Allah), famously used this phrase in the mid-1970s, to describe the challenge of establishing an Islamic bank at a time when there was virtually no Islamic finance model to emulate or learn from.

H.E. Dr. Mohammad Y. Al-Hashel, Governor of the Central Bank of Kuwait (CBK) in his keynote address during the CBK International Banking Conference in September 2019, described the global finance industry as being in “a battle for relevance and agility”. The respected Governor’s words carry a wealth of wisdom, significantly relevant to the subject of this article. Indeed, Islamic finance is also striving to remain relevant and agile, and one way to do this is to continuously adapt and implement standards to address the evolving and emerging regulatory issues. This holds increasing importance as Islamic finance is now categorised as systemically important in twelve jurisdictions – Bahrain, Bangladesh, Brunei, Djibouti, Iran, Jordan, Kuwait, Malaysia, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, and the UAE – where the market shares have reached 15% and above.

Empirical evidence shows varying degrees of implementation of Islamic finance regulations issued by the three relevant international standards-setting bodies – Malaysia-based Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB), and Bahrain-based, Accounting and Auditing Organisation for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI) and the International Islamic Financial Market (IIFM) – across the jurisdictions.

In general, the regulatory issues addressed in the reforms by these three bodies provide both opportunities and challenges to the Islamic financial services industry (IFSI). For example, the IFSB – which complements among others, the work of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) – has, as of June 2019, issued 22 Standards and Guiding Principles, six Guidance Notes and two Technical Notes since its inception in 2002. It also has a strong membership of 76 regulatory and supervisory authorities (RSAs) from jurisdictions in which Islamic finance is practised. However, according to the respondents of the IFSB’s Standards Implementation Survey of 2018, RSA respondents indicated that only 36% of the overall IFSB Standards and Guidelines (SAGs) have been implemented. This is a 2% reduction from 2017 (IFSI Stability Report, 2018). The respondents also indicated that 44% of the IFSB SAGs are being considered for implementation. This considerably low implementation rate highlights two significant challenges for supervisors regulating Islamic finance. First, a lack of consistent implementation produces huge regulatory gaps among countries, and second, evolving and emerging issues create an issue of priorities and brings more challenging conditions for supervisors and Islamic banks.

Empirical evidence shows varying degrees of implementation of Islamic finance regulations issued by the three relevant international standards-setting bodies – Malaysia-based Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB), and Bahrain-based, Accounting and Auditing Organisation for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI) and the International Islamic Financial Market (IIFM) – across the jurisdictions.

In general, the regulatory issues addressed in the reforms by these three bodies provide both opportunities and challenges to the Islamic financial services industry (IFSI). For example, the IFSB – which complements among others, the work of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) – has, as of June 2019, issued 22 Standards and Guiding Principles, six Guidance Notes and two Technical Notes since its inception in 2002. It also has a strong membership of 76 regulatory and supervisory authorities (RSAs) from jurisdictions in which Islamic finance is practised. However, according to the respondents of the IFSB’s Standards Implementation Survey of 2018, RSA respondents indicated that only 36% of the overall IFSB Standards and Guidelines (SAGs) have been implemented. This is a 2% reduction from 2017 (IFSI Stability Report, 2018). The respondents also indicated that 44% of the IFSB SAGs are being considered for implementation. This considerably low implementation rate highlights two significant challenges for supervisors regulating Islamic finance. First, a lack of consistent implementation produces huge regulatory gaps among countries, and second, evolving and emerging issues create an issue of priorities and brings more challenging conditions for supervisors and Islamic banks.

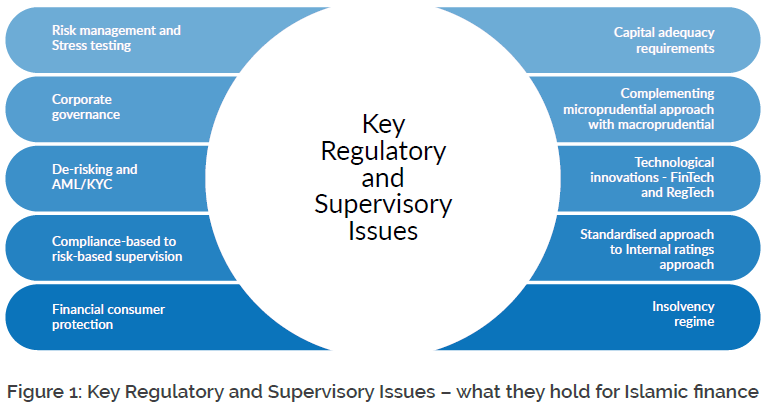

Many of the regulatory reforms in recent years have addressed issues of risk management, corporate governance, enhanced capital requirements, stress testing, macroprudential measures, risk-based supervision, FinTech and RegTech, IFRS 9, de-risking, consumer protection and insolvency regime, among others. No doubt, the global financial system has been strengthened by these reforms, and efforts are continuing by the international organisations mandated with the task to maintain the industry’s soundness and stability. The key issues that remain are what do these reforms mean for RSAs regulating Islamic finance, and how far has the IFSI come in addressing these regulatory issues. These are the questions this article aims to explore.

Key Regulatory and Supervisory Issues – what they hold for Islamic finance

Risk Management

Since the IFSB issued its Guiding Principles of Risk Management (IFSB-1) in 2005, there have been a lot of improvements and enhancements in risk management guidance, regulations and practices in the conventional space. Although IFSB is yet to update IFSB-1, it has taken into account some updates in other SAGs such as IFSB-13 (Stress Testing), IFSB-16 (Supervisory Review Process), IFSB-17 (Core Principles), and most recently ED-23 (that is the revised IFSB-15 on Capital Adequacy requirements). ED-23 proposes a modified definition of operational risk to accommodate new emerging risks such as cybersecurity risk together with internal loss multiplier, and credit risk weights adjustments for the treatment of individual exposure.

Stress testing has been the core of risk management discussions post-GFC. In this regard, IFSB-13 provides useful recommendations to the RSAs for Islamic banks. The only issue, which seems to be of significance, is the IFSB’s inability to decouple the updates to stress testing from the conventional templates such as those from IMF. The IFSB should issue its own (separate) templates reflecting Islamic banks’ balance sheets and specificities, which would ensure it remains relevant and usable should there be any revisions in the IMF templates. Specific guidance on this would be helpful to the supervisors.

Corporate Governance

Recent research by the IMF offers a granular look at the progress of the banking sector regulations and supervision since the GFC in the context of the 29 Basel Core Principles (BCPs). It shows that across the financial sector, two of the most problematic areas are corporate governance and regulatory oversight. The BCBS has issued two revisions of its Corporate Governance Principles requirements and updates since 2010, which are equally applicable to Islamic banks. The IFSB issued its Guiding Principles on Corporate Governance (IFSB-3) in 2006 and has yet to be revised, though revision is planned under the IFSB’s SPP 2019-2022. This prolonged delay in addressing the new requirements for Islamic banks puts significant pressure on supervisors as to what guidance is to be applied, given that the IFSB has not endorsed the changes by the BCBS.

Capital Adequacy Requirements (CAR)

These have been a central element of the BCBS’s response to the GFC. Post-GFC issuances of Basel 2.5 and Basel III have primarily focused on the numerator of the CAR that is, improving the quality and quantity of the regulatory capital together with systematic measures. While these reforms have helped to strengthen the global banking system, a major gap remains in the regulatory framework – i.e. the way in which risk- weighted assets (RWAs) are to be calculated due to the complexity and opaqueness of internal models, the degree of discretion in modelling risk parameters, and the use of national discretions.

In response to this, the Basel III reforms, finalised in 2017 and 2018, focus primarily on the denominator of the CAR (i.e. credit, market, and operational risks) and seek to restore the credibility of RWA calculations by enhancing the robustness and risk sensitivity of the standardised approaches for credit and operational risks. The IFSB has focused significant efforts on CAR, ensuring a level playing field for the IFSI. It has revised IFSB-2 (issued in 2007), introducing IFSB- 15 in 2013, and ED-23 in 2019, which is basically a revised IFSB-15.

These revisions are not without challenges as supervisors who have started implementing the IFSB Capital Adequacy framework have a puzzling choice to make – do they start from the beginning or from the most recent update. The former is easier to implement, while the latter without the former would not constitute best practices, nor can be practical and robust. In this scenario, the recommended approach would be to give Islamic banks adequate transitioning arrangements to allow them time to cope with, and adopt the latest changes and relevant internal requirements.

Complementing Microprudential Approach with Macroprudential Measures

Typically, prudential supervision has mainly focused on assessing whether individual financial institutions meet the statutory requirements in terms of solvency, liquidity and operations. One crucial lesson from the GFC was that individual institutions’ compliance does not guarantee financial system stability. In this respect, a new consensus has emerged that alongside monetary policy and microprudential supervision, macroprudential regulation and supervision are also needed to maintain financial stability and to address systemic risk.

In dual banking systems, where both conventional and Islamic banks operate side by side, there is still scant understanding of how best to structure the supervisory approach within the macroprudential policy framework, which requires distribution of responsibilities between the different actors responsible for these domains. While the BCBS has published guidance for supervisors, the IFSB is yet to issue any specific guidance on the macroprudential measures and supervision catering to Islamic banking specificities.

This could include developing and operationalising a rigorous analytical framework with clear criteria for risk identification and prioritisation for RSAs for Islamic banks. It is equally important to identify and calibrate the tools and instruments suitable for Islamic banks. The questions could be: how should the macroprudential policy framework be structured for measuring and monitoring systemic risk for Islamic banks, which instruments should be used, how, and under what conditions? In this context, perhaps an IFSB SAG on macro-prudential measures and supervision can provide guidance to the RSAs.

De-risking and AML/KYC

De-risking refers to the phenomenon of financial institutions terminating or restricting business relationships with clients to avoid, rather than manage, risks as identified in the Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering’s (FATF) risk- based approach. This is a new phenomenon for Islamic banks globally due to strict compliance to anti-money laundering (AML) and know-your- customer (KYC) principles, where recently many Islamic banks have been fined by their regulators for AML/KYC non-compliance.

A 2019 IFSB-AMF joint study noted that AML/ KYC Principles are equally applicable to Islamic banks. This is one area where RSAs will not have much difficulty in ensuring a level-playing field. De-risking brings candid concerns of instability in the financial sector due to the fear of building up of illicit markets and financial exclusion, thus undermining the integrity of the entire financial sector. De-risking measures by banks have the potential to turn legitimate businesses into a more-risky, less-regulated and/or unregulated alternatives such as Hewala (i.e. an informal system for transferring money without money movement) and shadow banking (i.e. credit intermediation involving entities and activities outside of the regular banking system).

As large correspondent banks move out of the higher-risk areas, their “risky” customers (entities and persons) will be forced to enter into the less-regulated or unregulated channels, generating potential systemic risks. It is thus equally important for the IFSB to put efforts into addressing developments pertaining to issues faced by Islamic financial institutions in relation to correspondent banks and de-risking, and provide detailed guidance on assessments and implications of “de-risking” in the Islamic finance context to supervisors.

Technological Transformation and Innovation The terms FinTech and RegTech are the current buzzwords and are part of the industry’s new mantra. RSAs are at the crossroads of this new paradigm, facing the formidable challenge of striking a balance between financial stability, innovation and designing a “fit for purpose” regulatory and supervisory regime, which embraces FinTech and RegTech. While the traditional view of credit underwriting standards is being transformed in the FinTech space, a key question is how supervisors will judge the quality of credit underwriting and the effectiveness of run-off rates in LCR under these new methodologies.

Cyber-security risk is another example directly relevant for supervisors as more consumers and businesses rely on digital platforms. An increasingly IT-reliant banking system exposes it to a growing and evolving set of operational risks. RegTech – i.e. use of technology to enhance capabilities of supervisors – promises to disrupt the regulatory landscape by providing agility, speed and data-driven outputs to the ever-increasing demands of compliance within the financial industry. The supervisory challenge is to conceptualise and implement the far-reaching possibilities of RegTech to develop a financial ecosystem, which is safer, stable and more efficient. The IFSB is yet to issue any specific guidance on a ‘regulatory sandbox’ approach highlighting the implications of FinTech and RegTech for supervisors regulating Islamic banks.

‘Compliance-Based’ to ‘Risk-Based’ Supervision (RBS)

Post-GFC saw supervisors focused on improving supervision. A recent IMF research highlights issues of weaknesses in the supervisory approach and proposes developing forward-looking risk assessments (such as RBS) of banks’ risk profiles, and effective approaches to early intervention and resolution. The RBS is a forward-looking approach, which evaluates both present and future risks. This is a departure from the earlier compliance-focused and transaction-based approach called “CAMELS” which typically covers point-in-time supervisory assessments. This requires supervision to become more risk-based and forward-looking, and not only monitoring financial indicators that may, to some extent, be backward-looking in nature. It also requires delving into less well-known areas, such as the business model, culture and conduct, and governance of an Islamic financial institution.

In many countries, the application of RBS to Islamic banks is still new and not well-developed. In many cases, specific tools and methodologies need to be established to supervise Islamic banks, which are able to assess their unique risks (including transformation of risk) and vulnerabilities. The IFSB is yet to issue any specific prudential guidance on this. It is important to highlight that the RBS process focuses heavily on off-site surveillance and is extremely data and resource-intensive. In this respect, adequate off-site surveillance tools for the RBS of Islamic banks should be enhanced.

There is a need to combine the analysis of financial statements, supervisory reporting and on-site inspections with stress testing exercises to assess banks’ resilience under different risk scenarios. It could mean adjusting rating methodologies, such as CAMELS, to cater to the peculiar nature of risks (including transformation and commingling of risk, and Shari’a governance) in harmony with the IFSB standards.

Standardised Approach to Internal Ratings Approaych (IRB) (under IFRS 9)

It is explicable that the BCBS has required both approaches (i.e. standardised approach and IRB) for credit risk measurement since the issuance of Basel II in 2006. On the other hand, the IFSB has so far only issued the standardised approach for credit risk measurement for Islamic banks. The shift in setting ‘provisions’ to expected credit losses (ECL) through the implementation of IFRS-9 and its equivalent AAOIFI FAS-30 has changed the game for supervisors as most of the jurisdictions supervising Islamic finance seem to be within the standardised approach.

At the same time, to implement the ECL approach, neither Islamic banks nor their supervisors were prepared in terms of historical loss data collection for various Shari’a-compliant contracts, probability of default (PD), and loss-given default (LGD) to name a few. While the implementation of IFRS-9 and its equivalent AAOIFI FAS-30 might be a step closer to IRB implementation and enhancement to ICAAP; proper guidance is needed for Islamic banks on the IRB. The IFSB, with its mandate on prudential supervision, should issue specific guidance on the implementation of IFRS-9 and its equivalent AAOIFI FAS-30.

Financial Consumer Protection and Insolvency Regime

Both these elements are underdeveloped in the Islamic finance industry. While some efforts have been undertaken by the IFSB, it is yet to introduce specific prudential guidance on these issues. Consumer protection has gained more attention in the aftermath of the GFC as consumers face more sophisticated, unique, and complex financial products and markets. From a supervisory perspective, financial consumer protection is needed to ensure that consumers receive adequate and easy-to-understand information, are not subject to unfair or deceptive practices and have recourse to fair redress mechanisms to resolve disputes.

It is, and should be, an integral part of the legal, regulatory and supervisory framework. A robust consumer protection regime for Islamic banking and finance is pertinent. In dual banking systems, it is quite challenging for the RSA to implement a consumer protection regime for Islamic banks in the absence of certain measures for consumer protection in the conventional system. Seen broadly, measures for financial consumer protection in a conventional system are also applicable in Islamic finance with minor adjustments due to the specificities.

Some issues that require consideration may include Shari’a-compliance as an essential and distinguishing product feature, financing business, deposit business and damage containment for Islamic banking consumers, and Islamic specificities in dispute resolution and damage containment in (near) failure cases. In this context, in establishing an effective national consumer protection regime, RSAs should review and assess their legislative framework (legal, regulatory and supervisory framework) to see whether it sets out financial consumer protection objectives and responsibilities for conduct of business with regard to Islamic banking products and services and whether it provides a clear definition of the scope of consumer protection mechanisms (consumers vs. retail investors).

Insolvency Regimes

Insolvency regimes also play a key role in the financial sector. An efficient recovery and resolution regime, as well as a robust bankruptcy and/or insolvency procedure, is essential for maintaining financial stability. The regime should address and cover the specificities of Islamic financial institutions. Among them are priority of claims, asset sale and transfers, the treatment of assets funded by PSIAs and the rights of investment account holders, ownership of the assets jointly funded by PSIA and the institution, treatment of reserves such as PER and IRR, legal governance and enforceability of Shari’a contracts in the resolution regime. A Task Force on this issue has been set up bu IFSB to develop specific guidance to the supervisors.

Conclusion

In any banking system, it is vital for supervisors to promote a level-playing field. This supervisory role becomes more complicated in a dual-banking system with a sizeable Islamic banking component as the regulator is required to supervise two sets of banking institutions with different risk characteristics while ensuring a consistent regulatory regime.

While too many to mention in this article, each specific risk characteristic of Islamic banks would ideally require separate guidance from the IFSB, or relevant standard-setting body, to ease and support this challenging supervisory role. Effective regulation and supervision requires continuous strengthening of regulatory capabilities in line with the relevant Islamic finance standards, to ensure the resilience and stability of the overall financial system.

The implementation of the IFSB prudential standards is one way forward to achieve effective supervision of Islamic banking within a jurisdiction. Regular and consistent application of the available IFSB prudential standards will reduce the likelihood of RSAs facing bigger issues with the supervision of the Islamic banks as new rules emerge. To succeed in this effort, RSAs need to be cognisant of the evolving and emerging regulatory issues, as well as address the lack of adequate supervisory expertise in Islamic finance.

Requisite continuous training and capacity development for supervisors is essential to develop, nurture and equip scarce supervisors to be effective and efficient in dealing with peculiar risks of Islamic finance. There is also a strong need to have a formal unit with a clear mandate within a central bank or supervisory authority to formulate and issue Islamic finance-related policies and regulations, as well as oversee their implementation in line with the IFSB and AAOIFI standards. This unit should work closely with other departments within the RSA in order to integrate Islamic finance with the overall financial system. These efforts are crucial to help RSAs achieve the long-term sustainability of growth, stability and resilience of Islamic finance.