Introduction

North America, Canada and the United States in particular, have some of the world’s most heavily regulated financial systems. Turmoil in United States markets with spillover effects into the rest of the world, has accentuated the need for re-thinking regulation. This puts a spotlight on the role that Islamic investment may play in filling gaps resulting from defunct institutions and reviving stagnant capital. While further integration and inflow into the North American economy is required, significant progress has already been made in the structuring and selling of Shari’a-compliant investment products within the existing framework of North American legal systems. The proliferation of Islamic banking and finance in highly regulated markets may usher in a better under- standing of Islamic precepts and the role they can play in the world economy.

Major hurdles

There are major hurdles to the full-scale development of Islamic finance in the North American and world economy. For example, European lawyers like Paul Wouters observe that:

“There are ongoing complaints on the lack of PLS partnership funding at commercial/retail Islamic banks. Islamic banks indeed mostly stick to equity-based finance contracts, such murahaba and ijara. These complaints are without merit, since this kind of equity venturing simply is not (and will never be) their line of business.”

Other Europe-based commentators, like A.L.M. Abdul Gafoor, have made the case for equity-based financing in works like Participatory Financing through Investment Banks and Commercial Banks. In the opening remarks of his book, Gafoor states:

“Islamic bankers have introduced the concepts of investment accounts and profit-and-loss sharing into commercial banking. In practice, depositor’s funds in the investment accounts are used by the Islamic banks to finance projects by entrepreneurs. The profits (and losses) are shared by the three participating parties – depositor, bank and the entrepreneur – in a pre-arranged ratio. They have, however, run into serious difficulties in implementing it, mainly because it is applied to situations where it is inappropriate.”

One of the situations where PLS arrangements are in-appropriate is within commercial banks in Canada, the United States and most other Western countries. For these countries, many of which are grappling with the issue of how to integrate Islamic finance into their conventional systems, the main hurdle is regulatory.

The problem of bank deposit guarantees

The core issue with regard to commercial banking is guarantee of bank deposits, mandated and regulated by financial regulators. This will always be an issue for banks as long as Basel II remains the bedrock of international banking law.

Some North American banks, like University Islamic Bank, have tried to develop Shari’a-compliant products that also comply with United States financial law. University Islamic Bank launched limited musharaka deposit accounts. These limited musharaka products were structured closer to investment vehicles than to bank deposits. This follows the lead by pioneer European institutions like the Islamic Bank of Britain (IBB). IBB gives customers the choice as to whether they want the bank to ‘top up’ any shortfall in their deposit accounts or stay true to PLS principles by relinquishing any legally-man- dated, but spiritually-bereft, right to the shortfall.

Canadian institutions have yet to offer Islamic deposits, either through a “Window” at the existing conventional banks or through a stand-alone institution. Several institutions have applied for an Islamic banking license but, to date, none have been granted. Concerns about authenticity and the chasm between the need to guarantee bank deposits under Basel-influenced law and the Shari’a precept that nothing is guaranteed may explain Canadian reticence. Canadian business publications have reported on the slow-moving process and pondered if Canada, despite its multicultural mosaic, is falling behind other nations in its development of a fully representative finance sector.

After Britain, Canada’s other progenitor nation, France, has issued tax and regulatory changes designed to lower transaction costs for Islamic finance and foster the development of the growing global sector within the country. Meanwhile, the French Minister of Economy, Industry and Employment publicly expressed her desire to woo Islamic investors and funds to local markets.

In material like the seminal book Honest Money, John Tomlinson, an Oxford-based Canadian economist, states that a true economy is one backed by actual rather than theoretical assets. Is it possible to do Islamic asset-backed financing in North America? We will answer this question in the context of Islamic mortgages, sukuk and other Shari’a-guided offerings.

Challenges for Islamic mortgages

The pioneering Islamic finance companies in North America, like Guidance Financial LLC in the United States and the Canadian housing cooperatives, are mortgage providers. These companies have three potential structuring choices under the Shari’a: murahaba, ijara and diminishing musharaka.

In his seminal book, Introduction to Islamic Finance, Sheikh Taqi Usmani discussed the limited use and applicability of murahaba by stating:

“Originally, murahaba is a particular type of sale and not a mode of financing. The ideal mode of financing according to Shari’a is mudaraba or musharaka… How- ever, in the perspective of the current economic set up, there are certain practical difficulties in using mudaraba and musharaka instruments in some areas of financing. Therefore, the contemporary Shari’a experts have allowed, subject to certain conditions, the use of the murahaba on deferred payment basis as a mode of financing. But there are two essential points which must be fully understood in this respect:

1. It should never be overlooked that, originally, murahaba was not a mode of financing. It is only a device to escape from ‘interest’ and not an ideal instrument for carrying out the real economic objectives of Islam. Therefore, this instrument should be used as a transitory step and its use should be restricted only to those cases where mudaraba or musharaka are not practicable.

The second important point is that the murahaba transaction does not come into existence by merely replacing the word of ‘interest’ by the words of ‘profit’ or ‘mark-up’. Actually, murahaba as a mode of finance has been allowed by the Shari’a scholars with some conditions. Unless these conditions are fully observed, murahaba is not permissible. In fact, it is the observance of these conditions which can draw a clear line of distinction between an interest-bearing loan and a transaction of murahaba. If these conditions are neglected, the transaction becomes invalid according to Shari’a.

By way of example, under the rules governing murahaba transactions, the bank is supposed to purchase the required assets and then sell them to the client at a pre-determined mark-up. Within the North American context, murahaba mortgages are problematic for two reasons. Firstly, banks and related financial institutions like credit unions are only allowed to own real estate in distress situations like re-possession and power of sale. This means that, when using murahaba, banks can, at most, purchase real estate nominally in their own name and then immediately transfer the property over to the client. This triggered two assessments of land transfer tax (much like the double stamp duty which afflicted the Islamic market in the UK in the early days of its growth). In Canada, this can be solved by the preparation of a trust document, wherein the bank is buying as a trustee from the beneficiary client and then the client takes the property in their own name.

The issue of immediate transfer of asset from bank to client, often by a mere click in a lawyer’s office, is not limited to the North American market. It is an issue for the murahaba market the world over.

The second problem relates to the rule that mark-ups in murahaba transactions cannot change; once the price is set, the client knows exactly what they have to pay to purchase the property outright and any subsequent variation in the price will render the transaction un-Islamic. The fact that “cost of borrowing” must be disclosed under most mortgage legislation in North America encourages complete transparency on the mark-up. How- ever, North American murahaba providers invariably obtain the source of funds from conventional financial institutions. The providers benchmark their internal rate of return to the prevailing rate of interest, which is subsumed within the monthly murahaba payment the client makes. More critically, due to variation in the prevailing interest rate, the funds provided under North American murahaba products are subject to refinance. Upon refinance, the amount due to the provider may change, thereby invalidate the murahaba and render the whole enterprise un-Islamic.

This is why companies that started with murahaba offerings in North America ultimately switched to one of the two other structures. However, a switch to the other structures involves a similar set of problems: under a true ijara, the lender must own the actual title to the real estate and lease it to the client under a lease-to-own arrangement until the client is in a position to purchase the property outright. At that time, title is supposed to be transferred to the client. Due to the prohibition against banks owning real estate, cooperative corporations in North America are the only companies offering ijara-based products. They can also deal with the issue of double land transfer tax by declarations of trust.

Finally, when it comes to diminishing musharaka, both the lender and the client are supposed to have joint ownership. This is where the prohibition against ownership also causes a problem. Islamic mortgage providers are starting to use more sophisticated providers like mortgage investment corporations, which are subject to the same prohibition. However, investors in these corporations are able to encourage the fund sponsors to take on responsibilities that come closer to the joint responsibilities required under sharikah principles like joint payment of property taxes, utilities and any forms of insurance mandated by law.

Enabling mechanisms

Within North America, the greatest advances have come not from amendments to existing financial laws but from Shari’a-inspired guidelines and codes, so-called “soft law.” One of the most crucial advances has been the fatwa on the Dow Jones Islamic Index. As stated by Michael McMillen,

“In 1998 (amended in 2003), the Shari’a board of the Dow Jones Islamic Market Indexes issued a fatwa…that constitutes one of the most monumental enabling developments in modern Islamic finance.”

The reason the fatwa was so important was because it allowed devout Muslims to participate in equity markets in a ‘practical’ manner, in that they could invest in companies that earned income from impure sources (like airlines which sold alcohol, supermarkets that sold pork, media companies who showed pornography) and, at the same time, provided a mechanism for cleansing impure income from their investment portfolio.

Sukuk

In North American regimes, the payment of interest is often legislated: by way of example, laws governing court systems will automatically embed the right to an award for pre-and post-judgment interest to the victorious party in concluded cases; in every bank mortgage transaction, there are standard charge terms that are considered part and parcel of the mortgage transaction (which may give the bank the power to compound any interest payable in the case of default)240 and income tax legislation often imputes income in no interest or low-interest loans between related parties.

In the same vein, there are benefits accruing to parties who earn interest income due to special exemptions in income tax laws. For example, portfolio interest income is exempt from American withholding taxes. sukuk in-come is fixed but not guaranteed. As such, sukuk holders cannot benefit from this special exemption unless they specifically characterize their income as interest on American income tax forms. The Shari’a advisor to the underwriter of the first rated sukuk in the United States, offered by East Cameron Gas, was asked to consider the Shari’a compliance of such a characterization. In his fatwa, the advisor stated: “The undersigned Shari’a Advisor to Bema Securitization SAL understands and recognizes that the state and federal agencies which govern the commercial transactions that underlie the issuance of sukuk require that this transaction be characterized as a loan for the purposes of taxation. As such, the Funding Agreement document related to this transaction characterizes the financing advanced by this transaction as a loan, and contains references to lending, and to a rate of interest, in order to complete this characterization and thereby allow investors exemption from certain income-related taxes. All such references have been made to satisfy these regulatory requirements and are not reflective of the true nature of the actual transactions in which neither interest nor riba are present.”

This fatwa augurs well for the future stream of sukuk- financed projects in North America, including the recently announced Bear Mountain resort sukuk, wherein subscriptions will be used in the expansion of a golf course development on Vancouver Island.

Centres of excellence

While unexpected places like golf courses in British Columbia and unexpected people like wildcatters in Louisiana are driving forward the Islamic finance agenda within North America, the city-states of Manhattan and Washington D.C. are arguably the only North American centers of excellence for Islamic finance at present. New York-based companies have been at the forefront of two issues confronting the Islamic finance industry worldwide: product development and education. For example, New York conference producers like Terrapin and Finance IQ have organized a slew of Islamic finance seminars and conferences. A select number of law firms in New York are also instrumental in education and the organic growth of intellectual capital regarding Islamic finance in North America.244 However, while law firms are adept at structuring under a particular regulatory regime, they cannot comment on Shari’a authenticity. As such, any deals they have documented are subject to ultimate oversight by Shari’a scholars like Sheikh Taqi Usmani. In late 2007, Usmani made a fierce critique of prevalent sukuk structures by stating:

“Undoubtedly, Shari’a supervisory boards, academic councils, and legal seminars have given permission to Islamic banks to carry out certain operations that more closely resemble stratagems than actual transactions. Such permission, however, was granted in order to facilitate, under difficult circumstances, the figurative turning of the wheels for those institutions when they were few in number [and short of capital and human resources]. It was expected that Islamic banks would progress in time to genuine operations based on the objectives of an Islamic economic system and that they would distance themselves, even step by step, from what resembled interest-based enterprises. What is happening at the present time, however, is the opposite. Islamic financial institutions have now begun competing to present themselves with all of the same characteristics of the conventional, interest-based marketplace, and to offer new products that march backwards towards interest-based enterprises rather than away from these. Oftentimes these products are rushed to market using ploys that sound minds reject and bring laughter to enemies.”

Financial firms active in the New York market like Shari- ah Capital, run by Eric Meyer, have launched innovative products like the world’s first Shari’a-compliant hedge fund and New York-based index providers like the Dow Jones have taken a leading role in the exponential growth of the industry. Meanwhile, in Washington, the US Department of the Treasury has developed a keen interest in Islamic finance and the capital region has hosted conferences, by organizations such as the National Council of U.S – Arab Relations, on Islamic finance and the global credit crisis.

Lawyers like Michael McMillen and sociologists like Sakia Sassen have commented on the emergence of globalized city-states with New York and London being pre-eminent and entrepots like Hong Kong and Georgetown, Grand Cayman being a distant second.

There is very strong political and economic will in all of these city-states to promote Islamic finance. For example, in the Cayman Islands, one can now register a corporation name in Arabic and local legislators have provided assurances that sukuk issuances will not be subject to onerous trust laws or mutual fund regulations.

On the other hand, in Canada, while the political will may not be as strong as in other countries, there is enough economic will in cities like Toronto for grass- roots growth of Islamic finance. By way of example, in mid-2009, the S&P launched an index of Shari’a-compliant equities on the Toronto Stock Exchange.

On the same day, Toronto-based Jovian Capital and UM Financial announced the launch of a Shari’a-compliant ETF that would be based on the S&P/TSX Sharia Index.

For Canadian sukuk issuers, offshore centers such as Luxembourg offer preferable tax withholding treatment than the Cayman Islands, due to applicable tax conventions) but corporate law regimes contain much more onerous requirements than that of the Cayman Islands.

While it is unlikely that Canada and the United States will be seeing Cayman-type changes to financial law, there is movement in the right direction in both countries, albeit at a much slower pace in the Canadian marketplace.

Brief comparisons

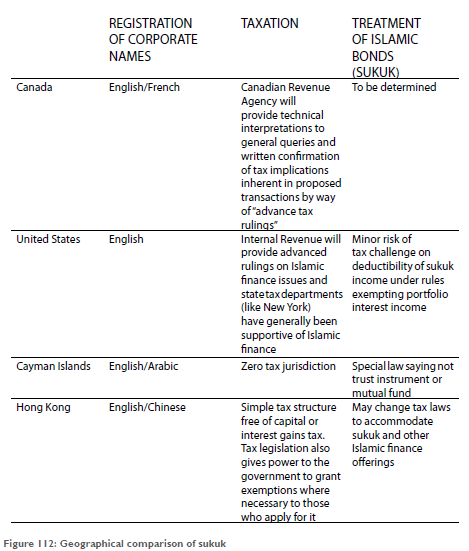

It is important to compare issues in corporate law, taxation and treatment of sukuk in different jurisdictions within North America, and the entrecotes beyond its borders, and determine what incremental improvements North American regulators can make to foster the growth of Islamic finance, to the benefit of both the host countries and outside investors:

National security regimes

A small but vocal number of neo-conservatives in the United States have attacked Islamic finance on the grounds that it is subject to lawsuits for misrepresentation, that Shari’a scholars (like Sheikh Taqi Usmani), who advise companies involved in Islamic finance, are calling for violent overthrow of Western governments and that monies donated to charity pursuant to portfolio purification are a source of terrorist financing. As pointed out in the Washington conference by the National Council of US Arab Relations, Islamic finance is about ‘business that is based on an ethical paradigm.’ Investors, non-Muslim and Muslim alike, are investing in Islamic finance in large numbers and are keenly aware of the excellent value proposition offered within many Islamic finance product lines. Perhaps the most striking example in North America was at the launch of the East Cameron Gas sukuk, where the majority of sukuk holders were conventional hedge fund managers. The value proposition behind Islamic finance and banking has now been endorsed by organizations as diverse as the Vatican and the UK Treasury. Regardless of the merits of Islamic finance, purveyors of the emergent source of finance in North America will have to contend with national security legislation that has arisen out of the United States Patriot Act and the Canadian Fintrac regime.