Financial engineering is a process of building complex instruments deploying basic building blocks or unbundling and repackaging different components of the existing financial instruments. In Islamic finance, the process of introducing a new product is subject to several Shari’a rules governing Islamic financial contracts, which is predominantly underpinned by variety of fiqh school of thought.

Financial engineering in Islamic finance should be geared towards the promotion of trade, partnership and risk-sharing. Furthermore, given the fact that Islamic financial markets are rather deficient in both liquidity and risk management tools, the dire need to come up with innovative products via financial engineering has become unneglectable.

It is also understood that successful financial engineering in Islamic finance may largely depend on a good grasp of the complexity of modern financial contracts coupled with comprehension in Shari’a principles governing the contracts. Although there has been a promising number of people who have mastered these two spectrums of discipline; the figure, however, is still relatively small, especially when compared to the immense need of financial products that could subsequently cater to the need of the society at large. This article, therefore, is an initial step in building a fundamental understanding of principles that could, hopefully, pave the way for innovations.

Fiqh-onomics of Financial Contracts

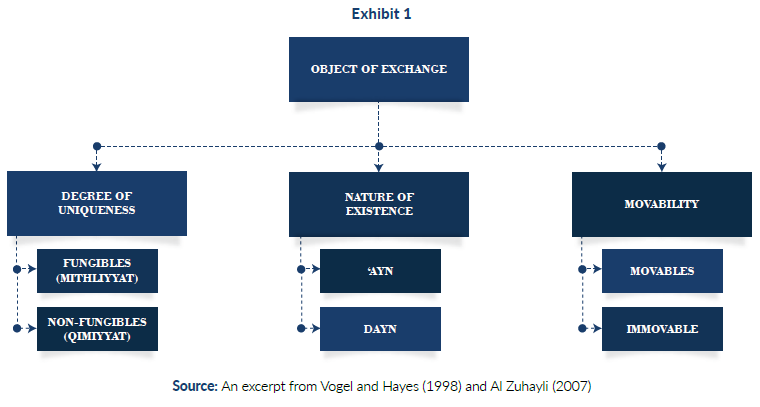

In a spirit of rejuvenating financial innovations in Islamic finance, this article attempts to examine the rules underpinning various financial contracts, which will be useful as guiding principles in financial engineering. In doing so, it establishes a classification of the objects of an exchange based on a) degree of uniqueness, b) nature of existence and c) level of movability as depicted in Exhibit 1.

One might wonder as to why it matters to grasp the classification of an object of exchange. The answer is pretty clear and straightforward; as different objects when exchanged (on the spot or deferred) could determine the lawful or unlawfulness of the financial contract. This is very fundamental for any financial engineer to comprehend, without which one could just end up mimicking the conventional financial products.

As shown in Exhibit 1, the objects of an exchange can be divided into fungibles (mithliyyat) and non-fungibles (qimiyyat), ‘ayn and dayn, and movables and immovable. Here, the third type of classification is not discussed as it does not fundamentally shape the law of financial contract in practice. Whereas understanding the insights of ‘ayn, dayn, mithliyyat and qimiyyat is very essential.

Vogel and Hayes (1998) define ‘ayn as a specific existing object, considered as a unique object and not solely as an indistinguishable member of a category.1 Dayn, however, is any property that a debtor owes, either now or in the future. Dayn is typically characterised by the fuqaha as a fungible (mithliyyat), such as silver or rice. Although in the current context, non-fungible manufactured goods can be treated as dayn. Dayn literally means “debt”, and it may also refer to the property, the subject of the obligation, considered to be already owned by the creditor.

The principal distinction between ‘ayn and dayn, as Vogel and Hayes (1998) suggest, not only depends on the degree of uniqueness but also on its existence. For instance, one could point at a specific existent object (‘ayn) by saying “this apartment”; as opposed to an object defined generically or abstractly by an obligation (dayn), such as party A enters into a contract committing to “deliver 1 kg of rice”.

In a sale contract, however, parties may exchange either type of objects within the following variation: ‘ayn for ‘ayn, ‘ayn for dayn, or dayn for dayn. The first, ‘ayn for ‘ayn is barter. ‘Ayn for dayn is the most common, and has several subcases, depending on whether one or both of the two counter values, the ‘ayn of the dayn, is delayed. The most basic sale is a present ‘ayn for a present dayn (spot transaction). The buyer gains immediate title to the sold ‘ayn, i.e., it becomes his/her property, and he/ she usually demands it at once from the seller. The seller also immediately “owns” the price as “dayn” in the buyer’s dhimmi’, i.e., as an obligation owed by the buyer. If the contract fixes a term of payment, the seller cannot demand the price until then.

The third subdivision of sale is the sale of dayn for dayn (bay’ al-dayn bi al-dayn). Many restrictions apply to these sales due primarily to forbidding the sale of “al-kali’ bi –al-kali”, which means the exchange of two things both “delayed”, or the exchange of a delayed (nasi’a) counter value for another delayed counter value. This article does not delve into the debate as to the “perceived to be” weak authentication of the Prophet’s hadith governing “al-kali’ bi –al-kali”. In any case, such a principle is said to have a near-universal application, and thus to have earned canonical authority as ijma’, or unanimous consensus.

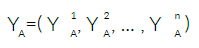

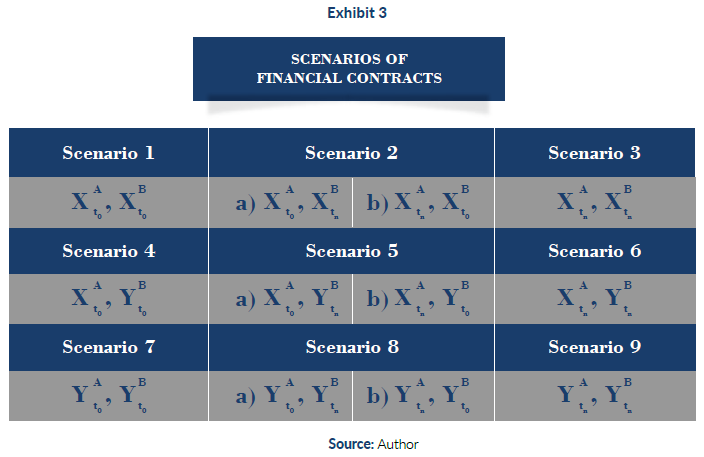

Given the variety of subdivision aforementioned, it is now important to come up with a series of possible scenarios resulting from various combinations of an exchange between ‘ayn and dayn. Suppose there are two parties, i.e. party A and party B intending to exchange a bundle of ‘ayn (X) and a bundle of dayn (Y).

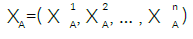

The configuration of A’s consumption bundle on ‘ayn and dayn is as follows:

Whereas B’s consumption bundle on ‘ayn and dayn can be defined as:

To slightly sharpen the understanding of various types of exchange, a time component is to be added, defined as t0 = cash (spot) and tn = (future delivery) where n > 0. As such, it will determine whether a certain contract is lawful or unlawful depending on the Shari’a rules that govern them.

Hence, a series of possible exchange scenarios resulting from Exhibit 2 are demonstrated in Exhibit 3 below.

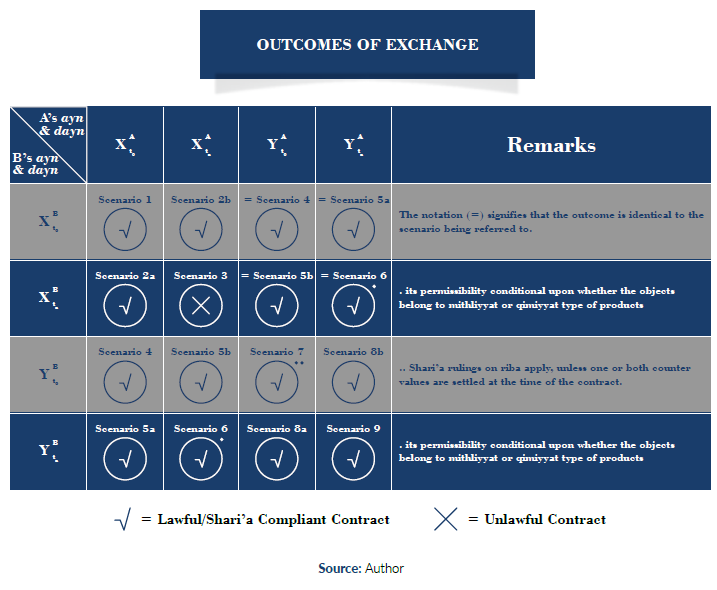

Exhibit 3 clearly shows twelve possible outcomes resulting from a number of exchanges between party A and party B taking into account different time zones. Scenario 1 is a contract of barter where an informal delay in one of the items does not necessarily nullify the contract. Scenario 2 may have a similar state of affair to scenario 1, in the sense that there isn’t any fundamental Shari’a issue that may void the contract irrespective of whether A’s ‘ayn or B’s ‘ayn is delivered now or later. Scenario 3 however, may be deemed unlawful. Nonetheless, various kinds of rights to rescind (khiyarat) can give rise to a legal right in the buyer to delay payment of price until the right to rescind ends.

Scenario 4 shows a common spot sale contract between the contracting parties; thus, it is clearly permissible. In scenario 5, a deferred delivery on either item is possible. Nevertheless, a rather tricky condition can occur if the item sold (‘ayn) is fungible (mithliyyat). If so, rules on salam may apply to such an exchange whereby the price must be settled in advance. Scenario 6 requires a caution; as the type of ‘ayn can determine the permissibility of the exchange. The transacting parties, therefore, need to differentiate between mithliyyat and qimiyyat products. If an ‘ayn being exchanged is non-fungible goods (qimiyyat), the fuqaha provide a space for its permissibility. It is understood that qimiyyat product does not make up for debt (dayn), thus a deferred delivery on qimiyyat products against a deferred delivery of another dayn is lawful. In other words, such a transaction is not tantamount to “al-kali bi al-kali” as described earlier. This matter would have had an entirely different judgment, should the products be categorised as fungible (mithliyyat).

In scenario 7, since it is dayn bi al-dayn unless one or both counter values is actually paid in contracting session, the contract will become unlawful. Some parameters that need careful attention are as follows:

- If both are currencies (not the same type), then it is sarf, requiring a spot delivery of both (the amount can be different)

- If it is between ribawi items as prescribed in the hadith of Prophet Muhammad SAW, the same rules apply

- If not a) or b), then one side must be paid now (recall rules on salam).

Scenario 8 demonstrates an unlawful contract as it is also dayn bi al-dayn. But if one of the two counter values is completely settled during the contract session, this makes it like ‘ayn, and hence it becomes lawful. The last scenario (9) is the state of contract that has persistently driven the debate in the Islamic finance industry. As understood, such a contract is considered unlawful since it is dayn bi al-dayn. To sum up the outcomes of the financial exchanges, Exhibit 4 below shows the results.

Conclusion

An unblemished understanding of the fundamental principles of financial contracts is essential, which requires a methodical approach and rigorous process. The explication presented in Exhibit 1 to 4 has an objective to easily help in understanding the guiding principles governing the variety of lawful contracts that could be the basis for financial engineering. Such an understanding is essential in the context of the future development of Islamic finance, which would be determined by its ability to develop genuine products that could serve the needs of the various segments of society.