Introduction

There is now a growing realization that Islamic finance needs to be considered seriously and deserves a level playing field with its conventional counterpart. One of the big hurdles in the development of Islamic finance has been taxation. Fundamentally, Islamic finance transactions are structured in a way that allows investors to receive returns in a form other than interest. This normally requires additional transactional steps which, in the absence of specific tax provisions, may be dealt by tax authorities individually and taxed in isolation. This generally results in additional tax costs, which make Islamic financial products less competitive to their conventional counterparts. These tax hurdles remain an impediment to the development of Islamic finance, and the global political atmosphere did not play a very helpful role in augmenting the industry. There still remains some degree of misconception that Islamic financial transactions equate to an implementation of Shari’a law. Hence there still remains a need for people to be educated, as far as Islamic finance principles are concerned. Given all this, there has been little incentive for key decision-makers in many countries to consider providing Islamic finance a level playing field in the mainstream financial services industry. Where the recent financial turmoil has severely dented leading economies, it has also changed the attitude of the regulators towards Islamic finance. For example, the French government, while openly displaying resentment for the Muslim veil, now boasts about the size of its Muslim population in order to attract investment by Islamic finance houses. However, this change of face is good for the growth of the Islamic financial sector as well as the global economy. The remaining impediment now is the lack of understanding of Islamic financial arrangements. The main Islamic finance products are described below with a summary of the key tax issues that arise with each product.

Product structures and related tax issues

Mudaraba, wakala and musharaka

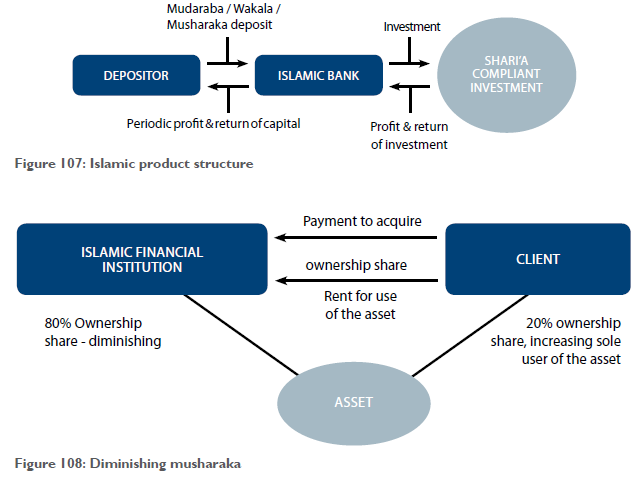

Mudaraba and wakala are both investment management arrangements between an investment manager and an investor. The investment manager may be paid a fee for his services or may participate in the profits of a venture on a pre-agreed ratio. It is also possible that the investment manager is paid a base fee as well as a share in the profits of the venture. In case a loss has sustained the investor(s) bear all the loss while the investment manager loses his service fee. A musharaka refers to a partnership where both parties to the arrangement contribute cash. The profit is shared on a pre-agreed ratio whereas any losses incurred in the venture are divided according to the ratio of investment. An Islamic bank normally raises deposits using a mudaraba, wakala or musharaka structure. While using mudaraba or wakala structures, the bank acts as the investment manager while the depositor is treated as the investor. Normally, a wakala structure is used for fixed deposit accounts whereas a mudaraba account is used to replace other conventional bank deposit arrangements. In a musharaka structure, the bank would mix the amount of deposit with its own funds and utilize the pool. The funds are invested in Shari’a-compliant ventures and products. The profits are shared between the bank and the depositor on a pre-agreed ratio. Although the depositor solely bears the risk of loss in a mudaraba or a wakala structure, the bank would normally, from a commercial perspective, ensure that enough reserves are maintained to avoid any unwanted situation.

Generally, the agreement between the bank and the depositor allows the bank to periodically calculate and pay the share of profit according to its own estimates and calculations. Normally, the agreement provides that the depositor would accept all such calculations without contesting, and that the decision of the bank would be binding on him. The depositor also authorizes the bank to charge appropriate fees and administrative costs, and retain the bank’s share in the profit. The agreement may also allow the bank to keep for itself anything over and above an agreed profit margin.

The structure is illustrated below.

- The share of ‘profit’ received by the depositor may not be treated as interest. In some jurisdictions, bank interest income is taxed at a preferential rate, and this may put the depositors of an Islamic bank at a disadvantage to depositors of a conventional bank.

In a musharaka structure, the bank and the depositor could be treated as partners in a partnership. In some jurisdictions, partnerships may be treated as separate taxable entities and so accordingly, there would be a requirement to file tax returns. An Islamic bank would therefore be treated as being in a partnership with each deposit holder. This would put administrative burden on the bank for filing a number of tax returns in respect of each such ‘partnership’. If this is the case, it would also place an administrative burden on the tax authorities for the management of such tax returns.

- In certain jurisdictions, partnerships are treated as transparent entities and any income generated is treated

as having been received by the partners directly from the underlying source. The depositor of an Islamic bank may therefore be treated as having received a share of the profit directly from the underlying investment or trading activity carried out by the bank. Accordingly, in addition to the higher tax burden, the depositor may also be required to file a tax return every year in respect of income from bank deposits, which may not be required for a depositor of a conventional bank. Even a student maintaining a deposit account with an Islamic bank could be subjected to filing annual tax returns.

- The payment of the share in ‘profit’ would not be treated as interest, and therefore may not qualify as a tax-deductible expense for the bank.

- Financial services are not usually subject to VAT. In the absence of a specific exemption, additional VAT costs may arise in respect of any service fee charged by an Islamic bank.

Mudaraba and wakala structures are also used in constituting Shari’a-compliant funds. The relationship between the investment manager and the fund is normally based on a fixed fee and/or a share in return generated by the fund. With small modifications, the arrangement be- tween an investment manager and a fund can be made Shari’a-compliant. Generally, this should not give rise to any tax anomalies.

- Diminishing musharaka

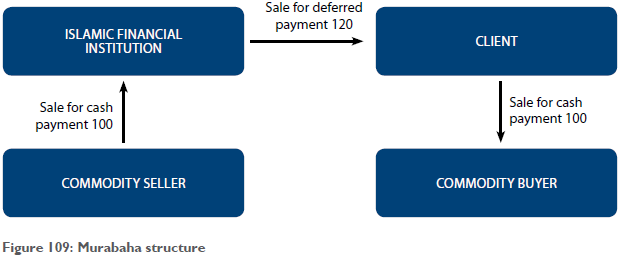

Diminishing musharaka is a special form of musharaka (partnership) which replaces the conventional asset-backed finance transactions and mortgages. As the name suggests, a diminishing musharaka is a partnership that reduces to zero over time. A typical diminishing musharaka arrangement is illustrated below.

The IFI and the client enter into a partnership agreement and the partnership acquires the asset or property selected by the client. The share of the IFI is divided into a number of units. The asset/property acquired in the name of the IFI (as a security), is leased to the client for an agreed periodic rent. Under a separate agreement, the client promises to purchase the units held by the IFI over an agreed period of time. Generally, it is provided that the value of the IFI units would not change over the period of the arrangement. The rent replaces interest while the purchase price for units is akin to repayment of capital under a conventional arrangement. With each purchase of units, the share of the client increases in the partnership which results in a corresponding reduction in the amount of rent payable.

A diminishing musharaka would generally give rise to the following tax issues that do not arise with its equivalent conventional transaction:

- The rental payment received by the IFI may be treated as leasing income or as property rental income as opposed to interest. This may lead to a higher tax charge for the Islamic financial institution, for e.g. property rental income which may be subject to tax at a higher rate as compared to interest income derived by a conventional bank. Moreover, deductibility of expenses against such income would be limited.

- The client may not be entitled to expense relief as is normally available in relation to interest expense on an asset-backed loan or a mortgage. A mortgage interest relief may not be available to an individual entering into a diminishing musharaka whereas the same would be available in relation to a mortgage with a conventional bank.

- As the title to the asset/property is held in the name of the IFI during the tenure of the arrangement, and is then transferred in the name of the client, the duplicate transfer of the property may give rise to an additional stamp duty charge.

- In most jurisdictions, tax relief is available to first-time home buyers, or an individual may be able to avail of certain reliefs; such as the first-time buyers’ relief, owner occupier relief or relief on acquiring a newly constructed property. These reliefs may not be fully available to an individual entering into a diminishing musharaka arrangement with an Islamic bank.

- In some jurisdictions, the entitlement to claim capital allowances is only available in respect of assets ‘owned’ by the entity. While a conventional asset-backed finance arrangement normally does not affect this relief, a person may not be able to claim capital allowances if the asset is acquired under a diminishing musharaka arrangement.

- Financial services are not usually subject to VAT. In the absence of a specific exemption, additional VAT cost may arise in respect of any lease rental payments made to the IFI.

- Murahaba

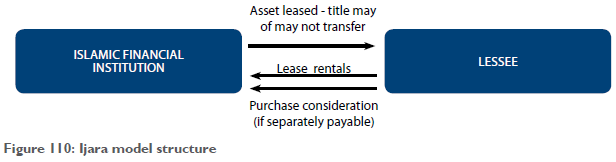

Murahaba replaces term loan arrangements and is also used to replace asset-backed finance transactions. It also caters for sale and lease-back transactions. It is an absolute sale on a marked up price, with the IFI (seller) disclosing its profit margin to the client (purchaser). The complete murahaba cycle is illustrated below.

Where cash is to be generated by the client, the commodity traded would be a product with a ready-sale market. Typically, copper is used as it is traded in the commodity exchange market. Gold or silver is not used as these are considered as currency under Shari’a, and more importantly cannot be traded on a deferred basis. The product will be sold by the client (at a loss) in order to generate cash of 100. The deferred liability of 120 towards the IFI is discharged over an agreed period of time. For asset-backed finance transactions, the asset is purchased by the IFI and is sold on to the client at a marked-up price payable over an agreed period of time.

A murahaba transaction would give rise to the follow- ing tax issues that do not arise with its conventional counterpart: In a conventional financing arrangement, interest takes the form of an effective annual yield. Accordingly, interest income and expense is recognized over the life of the transaction and a tax charge or relief gradually arises. In a murahaba transaction, the IFI may be treated as being engaged in the trade of buying and selling commodities. Since Shari’a principles don’t allow deferred payments to be discounted using an interest rate, there could be accelerated recognition of related income and expense and the tax treatment could accordingly be different. It may be noted that some Shari’a scholars have suggested that the difference between the original and the marked-up price could be amortized over a period of time. However, it is unclear as to what basis should be used for such amortization.

- As the arrangement involves several transfers of title for the same asset, the parties may be exposed to additional stamp duty or transfer tax charges.

- On the basis that an IFI would be actively entering into murahaba arrangements, it may be considered as being engaged in making taxable supplies from a VAT perspective. Such VAT cost may not be fully recoverable for the parties to the transaction. On the upside, this should improve the VAT recovery position of the IFI.

- Ijara

Fundamentally, an ijara contract is similar to a conventional lease and an ijara arrangement would normally refer to an operating lease. However, ijara arrangements are also used to structure finance leases or hire purchase transactions. An ijara arrangement is also involved in a diminishing musharaka arrangement, which replaces conventional asset-backed financing transactions and conventional mortgages.

The IFI either holds an inventory of assets in anticipation of customer demand for leases, or buys an asset at the specific request of its client. The asset thus acquired by the IFI is leased to the customer for an agreed rent payable over an agreed period of time.

During the period of the lease agreement, the asset re- mains the property of the owner. Accordingly, the owner would normally assume the burden of wear and tear. Moreover, if the asset is to be insured, the insurance expense must be borne by the owner-lessor. However, this cost may be factored into the calculation of the lease rental. The lease rentals should be specified in the lease agreement, although the amount can be fixed or variable. If the lessee defaults in making the lease rental payment, the lessor cannot charge any interest. How- ever, the lease agreement contract may require the lessee to make an additional payment towards a charitable cause. To enforce this, an ijara agreement would normally require the charity payment to be routed through the lessor. In a plain ijara arrangement, the asset is returned to the IFI on expiry of the lease period (as with an operating lease).

If the objective is to structure a finance lease equivalent arrangement, the lessor would promise to transfer the title of the asset to the lessee, either by way of a gift or at a token value. The promise is binding on the lessor

only, whereas the lessee has an option not to proceed with the transfer. Accordingly, where the transfer is subject to instructions from the lessee, it may be contingent upon a particular event, such as, full payment of all remaining lease instalments.

If the objective is to replace a conventional hire purchase arrangement, the lessee would make a promise to acquire the lessor’s interest in the asset over the lease term for an agreed price. In such a case, the lessor’s interest in the asset is divided into a number of units and the periodic lease rental payments are split between

(a) lease rental payment; and (b) payment for acquiring interest (units) in the asset. The lessee’s interest in the asset therefore typically increases over time with a corresponding decrease in the lessor’s interest. During the lease period, the legal title normally remains with the lessor.

An ijara structure is illustrated below.

In comparison to a conventional finance transaction, an Islamic ijara transaction would give rise to the following additional tax issues:

- If the tax law distinguishes between operating and finance leases, the taxation of an ijara may not equate to that of a conventional finance leasing arrangement, as the IFI may be considered to be earning rental in- come as opposed to interest. However, it should then be possible for the lessee to claim a tax deduction for the entire rental payment.

- As the asset is owned by the IFI and is used by the client in its trade, a situation may arise where neither party is entitled to claim capital allowances on the cost of the asset.

In a conventional asset-backed transaction, the asset is bought by the client in its own name and is kept under lien with the lending institution. In an ijara arrangement, the asset is acquired in the name of the IFI and the interest is then transferred to the client. This multiple transfer of title may entail additional stamp duty or other transfer taxes.

- General takaful, re-takaful and family takaful arrangements

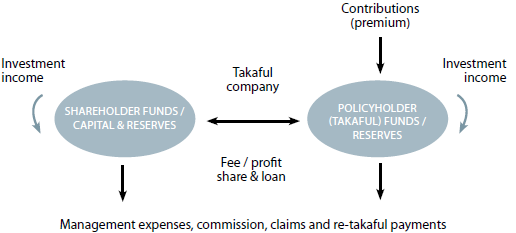

The word ‘takaful’ in the Arabic language means ‘guaranteeing’ or ‘taking care’ of each other. Based on the concept of social solidarity, cooperation and mutual indemnification of losses to members, takaful is an arrangement amongst a group of persons participating in a scheme, under which the takaful members (policyholders) jointly indemnify each other against any loss or damage that may arise to any one of them.

In broad terms, a takaful arrangement is similar to a mutual insurance with the difference that takaful members would normally not be share or unit holders in the taka- ful company, which operates the takaful fund. The company is paid a fee for its services and/or is entitled to a share in the return received on the fund’s investments. The term ‘general takaful’ is normally used as a reference to the general insurance arrangement while the term ‘family takaful’ would normally refer to a life assurance arrangement. A takaful arrangement can be illustrated as follows:

A retakaful (reinsurance) arrangement also works in a similar way where the takaful companies assume the role of takaful members and the re-takaful company assumes the role of the operator of the scheme.

The key defining characteristics of a takaful arrangement are as follows:

- A company sets up a takaful fund and invites contributions from persons (takaful members). Takaful members pool funds by way of contribution. This fund is used to make compensation (claim) payments for any loss or damage arising to any takaful member. The claim payments are generally restricted to actual damage or loss and the opportunity costs (such as loss of potential in- come) are generally ignored.

- The takaful company operates the whole arrangement relating to (a) the management and receipt of contributions, (b) claim management and payments, and (c) the management and operation of takaful fund.

- The company records takaful funds separately from its own share capital and reserves. Accordingly, a loss relating to takaful funds is charged to the takaful fund and ring-fenced from the company’s reserves. Likewise, a loss relating to the company’s investments/activities is borne by the company and ring-fenced from takaful funds. Normally, the company’s share capital and re- serves (including fee income) are used to pay marketing and management expenses and commission payments.

- The company would normally charge a fee for its services relating to the management and the operation of the takaful scheme and funds. The fee may either be fixed or a share in the returns on takaful investments. It is also possible that the company is paid a fixed fee and is also entitled to a share in the return received on takaful investments. The arrangement is normally set out in the insurance policy or other related documentation.

- If a shortfall arises in the takaful fund, the company would normally make an interest-free loan to the fund. Generally, the loan is repayable only out of a future sur- plus arising in the takaful fund. If subsequently, there is a surplus in the takaful fund, the surplus is first used for repayment of any interest-free loan owed to the company and the balance can either be reserved for future losses, or the company may decide to make a distribution to the policyholders. The distribution amount may be adjusted against the contribution payment relating to the following year.

- On dissolution or winding up of a takaful fund, any sur- plus in the fund may be distributed amongst those who contributed to it or amongst those who are members (policyholders) of the fund on the day of dissolution or winding up. The surplus or any part thereof may also be given to charity. The takaful funds cannot be diverted to the company.

- A retakaful works in a similar way to takaful. Various takaful companies participate in a re-takaful fund set up by a re-takaful company. The retakaful company acts as the operator of the re-takaful arrangement.

- In a family (or life) takaful arrangement, the amounts received from a member (policyholder) is split between a Contribution Account and an Investment Account. The split is generally based on the actuarial valuation of the associated risks, and is agreed with the policyholder at the time of issuance of the policy. The Contribution Account is generally reserved for life assurance claims. If the takaful member survives the policy term, the member is only entitled to receive the amount paid into the Investment account and any accumulated profits attributable to such amount.

- The profit made on takaful investments is apportioned amongst the policyholders (takaful members) or retained as a reserve for the future. The arrangement is normally set out in the insurance policy or other related documentation, as is the case with conventional life assurance.

As a takaful arrangement broadly works in the same way as a conventional insurance arrangement, there should be a limited risk of additional tax issues arising in relation to takaful arrangements. However, the following tax issues could be considered in this regard:

- In a general takaful arrangement, the contribution payment by a business may not be treated as a tax deductible expense for the reason that it is not an insurance premium per se. On the other hand, there could be scope for arguing against the applicability of insurance premium taxes.

- Insurance is generally treated as a financial service and is normally exempt from VAT. However, there could be VAT costs involved, specifically in relation to service fees charged by the takaful company.

- Sukuk

The term sukuk is the plural of sukuk which, in Arabic, refers to a bond or a security. Sukuk therefore is an investment in certificates. However, under Shari’a law, a paper itself has no value and it should only represent the value of some underlying commodity. A sukuk ar- rangement is therefore akin to the securitisation of an asset. However, the issuance of sukuk should be backed by some real assets.

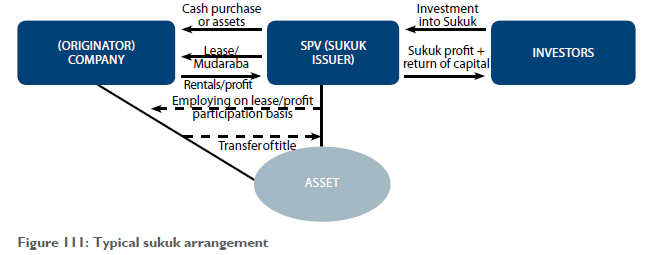

Fundamentally, the beneficial ownership of the assets is transferred by the originator company to an SPV. The SPV finances the purchase by issuing sukuk to investors. The SPV then employs those assets in a Shari’a-compliant mode to generate return for the investors.

Normally, the assets are either leased back to the originator company, or they are employed in the trade of the company on a profit participation basis. In either case, any income received on the re-employment of the assets is distributed by the SPV to the sukuk holders. Typically, the amount of rent paid to the SPV would match the profit payable by the SPV to the sukuk holders. At the expiry of the term of the sukuk bonds, the assets are generally acquired for cash by the originator. The SPV then uses the cash to redeem the sukuk (certificates).

The following tax issues are specific to sukuk, and are in addition to tax issues related to the retail structure which have been discussed earlier:

- The transfer of income-generating assets to the SPV and then back to the originator could give rise to an additional stamp duty (or transfer tax) charge.

- Profits paid by the sukuk SPV would have to be analyzed to establish whether they constitute a distribution of profits by the SPV, or business income from the underlying investment; as opposed to interest in a conventional transaction. This may affect the tax treatment of income received by the sukuk holders.

Additional tax implications arising on cross-border transactions

It would not be uncommon for business transactions in today’s world to have a cross-border element. This would be more relevant for an emerging industry, such as Islamic finance. Certain additional tax issues would arise if one party to an Islamic financial arrangement is located in a foreign territory. These would normally include:

- For equity-based financing arrangements, the investor may be considered to have a permanent establishment in the entrepreneur’s (borrower’s) country of residence and thus exposed to tax liability in that country. This could either be on the basis that the investor is deriving profit from a trade being carried out on a foreign soil, or deriving rental income in respect of an asset located abroad. Such PE issues, apart from taxation charge, may carry additional administrative burden, such as, filing of tax returns.

- Sourcing of income could be an issue and this would generally have consequential tax effects. This will be common in asset-backed financing arrangements and mortgages. Moreover, a sukuk-issuing SPV set up in a foreign country may be subject to tax in the originator’s country of residence, on the basis of deriving rental in- come or business profits from that country.

With reference to double tax treaties, profit payments to the Islamic financier would generally be considered as dividend (distribution of profits) rather than inter- est with consequential tax effects. Similarly, diminishing musharaka replacement of conventional mortgages would be treated as income from property which is generally taxable in the source jurisdiction, as opposed to interest income which is generally taxable in the destination jurisdiction (with limited or no taxation right to the source jurisdiction).

- In some situations, the tax residence of the borrower may be affected owing to ‘control and management’ issues arising with a non-resident Islamic finance partner. This should not be the case in most situations. However, if it arises and the tax residence is impaired, the entrepreneur may not be entitled to avail of tax treaty benefits.

- A duplicate (and irrecoverable) charge to VAT costs may arise, in the source as well as the destination jurisdiction.

Accounting for Islamic finance products

The expansion of Islamic finance creates a pressing need for harmonized international accounting standards. This is more relevant these days, given the fact that most of the prevailing accounting standards, such as, International Accounting Standards (or the International Financial Reporting Standards) cannot be applied across the board to Islamic financial transactions.

AAOIFI has published some accounting standards for Islamic financial institutions and industries which are being followed in certain Gulf States. In addition, certain other countries have also issued local accounting guidelines for Islamic financial products and services. However, for inherent limitations, a lot of variations arise in the ac- counting treatment under AAOIFI Accounting Standards as compared to other sets of accounting standards. For example, AAOIFI Standards require that all leases should be recognized as operating leases regardless of the fact that certain leases carry the characteristics of being recognized as finance leases.

The accounting standards issued by AAOIFI so far are limited to accounting for financial institutions, and do not provide guidance on the accounting treatment of the counterparties in quite a few instances. For example, the accounting treatment of the counterparty for a diminishing musharaka transaction is not clear, i.e. whether the asset should be recognized on the balance sheet, and if so, at what value, and how the progressive payments should be accounted. Considering that these Standards are at an evolutionary stage however, the framework of AAOIFI Standards does suggest that where accounting treatment is not provided for under AAOIFI Standards, the accounting treatment under any alternative accounting standards should be considered.

In some cases, the accounting practice adopted by market players in the Islamic financial industry does not conform to the legal and the Shari’a form of the transaction. For example, general takaful companies are recording the gross amount of premium as their income whereas under the rule of Shari’a, the takaful funds belong to the policyholders and cannot be diverted automatically to the takaful company.

In summary, as the accounting profit is normally a key determinant in the computation of taxable income in most countries, it is the need of the hour for the accounting profession to rise up to the challenge.

Looking ahead

Islamic finance has now come out of the infancy stage and yet there remains a need for a consistent accounting and tax treatment of Islamic financial transactions. Given that the Islamic financial market is growing at a fast pace, there is an urgent need to adopt a top-down approach. As a starting point, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) should take up the initiative and modify the model double taxation convention to accommodate Islamic financial transactions, and ensure that they are taxed on par with their conventional counterparts. Major financial centres (such as the UK, France, and Ireland) have already started the process of amending their tax laws to accommodate Islamic finance transactions. An initiative by the OECD will certainly boost the comfort level of other jurisdictions, and incentivize them to modify their local tax laws to make Islamic finance a mainstream part of their financial system. This can provide an alternative way of doing business which would certainly help in avoiding the current financial debacle that we have recently just witnessed.