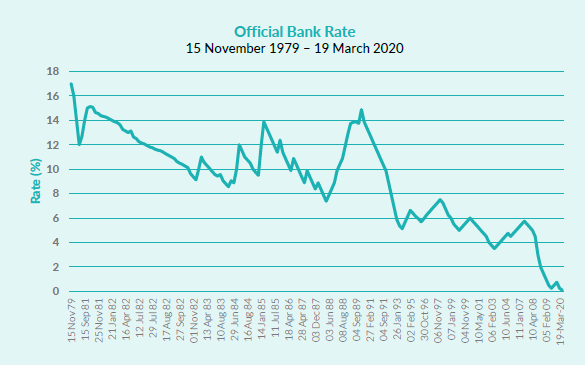

During the outbreak of COVID-19, the interest rates on both sides of the Atlantic are approaching the base and driving borrowing costs to historic lows. In the United Kingdom, the Bank of England (BOE) has revised the bank rate to 0.1%, its lowest ever, on March 19, 2020. In the United States, the Federal Reserve have maintained the federal funds rate or range at 0-0.25% since March 16, 2020.

Of great interest is the falling trend of the BOE base rate over time. The rate was at a peak at 17% on November 15, 1979 and has since gradually fallen to almost zero as of March 2020. The latest downward revision of the interest rate to 0.1% was intended to limit the economic fallout from COVID-19 – as if the natural law of gravity is showing the world a prescription against the root of all evil.

In a Muslim-majority country such as Malaysia, also proclaimed as a pioneer of Islamic finance, the Overnight Policy Rate (OPR) was reduced to 2% on May 5, 2020. While it is still uncertain whether the benchmark rate will be reduced further, maintaining such a positive base rate provides little incentive for a zero-interest rate policy.

Although the Muslim-majority population has learned that interest on lending and borrowing is prohibited, interest remains a banking norm and efforts to implement alternative financing practices seems far from satisfactory. In reality, real and financial markets have prospered with the help of credit instruments that are in turn ruled by interest rates. Islamic financial markets are vaguely distinctive. Walking the talk on Islamic finance has been a challenging task. A call to bridging the gap between theory and practice of Islamic finance can be found in our academic article entitled ‘Islamic corporate financing: does it promote profit and loss sharing?’ published in a renowned journal Business Ethics: A European Review (2016, Volume 25, Issue 4). This article essentially questioned whether Islamic financial instruments that charge profit rates are entirely different from interest-based credit instruments.

“Islamic corporate financing: does it promote profit and loss sharing? Published in a renowned journal Business Ethics: A European Review”

(2016, Volume 25, Issue 4)

Even during the period of calamity due to the COVID-19 outbreak, where six-month moratorium for loans was announced by the government, banks (Islamic and non-Islamic) in Malaysia seemed initially reluctant to waive additional interest or profit charges imposed following deferrals in instalments for hire- purchase loans. This incidence had triggered public outcry as banks were seen not doing enough to ease people’s financial burden during the time of need.

Although it was later announced that the additional interest or profit charges will be waived for the moratorium (dubbed as COVID-19 Financial Relief Scheme), such an incidence has already amplified scrutiny against the interest of Islamic hire-purchase providers.

In Malaysia, Islamic hire-purchase is commonly marketed as Al-Ijarah Thumma Al-Bai’ (AITAB). Interestingly, both AITAB and conventional hire-purchase are regulated through the Hire-Purchase Act 1967. By implication, the calculation of ‘term charges’ for both conventional and AITAB adopt the same formula as set out in the Sixth Schedule of the Act. The term charges are calculated on a simple interest basis at a rate specified in the agreement.

For example, if the term charges calculated as a rate per centum per annum specified in an AITAB agreement is 2.44%, the cash price of a vehicle is RM114,000 and repayment period is nine years (i.e., 108 months), then the monetary value of term charges is RM25,034 (i.e., 2.44% × RM114,000 × 9). Consequently, the total amount repayable by consumer is RM139,034 (i.e., RM114,000 + RM25,034).

Although an AITAB agreement may state that term charges are the profit rate that is used to calculate the rental rate for the Islamic hire-purchase, the use of an identical formula to calculate the interest rate for conventional hire-purchase raises eyebrows. One might as well argue that the bank is actually lending RM114,000 and charging RM25,034 in interest. The simple interest per month is approximately RM231.80 (i.e., RM25,034 / 108 months) to be paid by the consumer to the bank.

From a critical perspective, the ‘aqad’ paperwork and vehicle can be seen as disguising the money-lending activity of the bank. In reality, the bank has essentially ‘created’ deposit (money) of RM114,000 and loaned the money out to a consumer to buy the vehicle. Furthermore, the bank could generate profit more than RM25,034 from this money-lending activity.

If the bank invests every RM231.80 on the monthly interest it receives, and reinvests for every successive month during the repayment period, the bank will also profit from interest-on-interest. Following the Annual Percentage Rate (APR) for term charges as calculated in accordance with the formula set out in the Seventh Schedule of the Hire-Purchase Act 1967, the effective annual rate for the investment and reinvestment of interest income is 4.5%. This yields monthly reinvestment rate of approximately 0.375% (≈ 4.5% / 12).

By implication, using the monthly compounding concept of interest, the total interest and interest-on-interest earned by the bank throughout the 108 months is RM25,034 and RM5,759, respectively (Note: RM5,759 is the total interest earned on reinvesting every RM231.80 in interest on a monthly basis). This effectively means that when the bank lends RM114,000 in money that it had created, it could be receiving in return RM144,793 (i.e., RM114,000 + RM25,034 + RM5,759) though the consumer’s repayable amount is RM139,034.

One could gather from the above illustration that, by default, banks earn not only interest but also interest-on-interest (compound interest) through their money-creating, lending and reinvestment activities. The calculations of both simple interest and compound interest are provided in the Hire-Purchase Act 1967, which regulates both Islamic and conventional hire-purchase in Malaysia. According to the Section 4c(1)(c)(viii) of the Act, every hire-purchase agreement set out in a tabular form the APR for term charges, shall be calculated in accordance with the formula set out in the Seventh Schedule of the Act.

Not surprisingly if, in practice, the APR is not stated in an Islamic hire-purchase agreement.

By all means, such concealment (if any) does not necessarily suggest the absence of compounding interest practice. A bank is deemed not efficient if it let money sitting idle not earning anything. From this perspective, an attempt to distinguish Islamic banks (as practised) from their conventional counterparts is feared to have fraught consumers with confusion, if not deception.

INTEREST INCOMES AND REMUNERATION

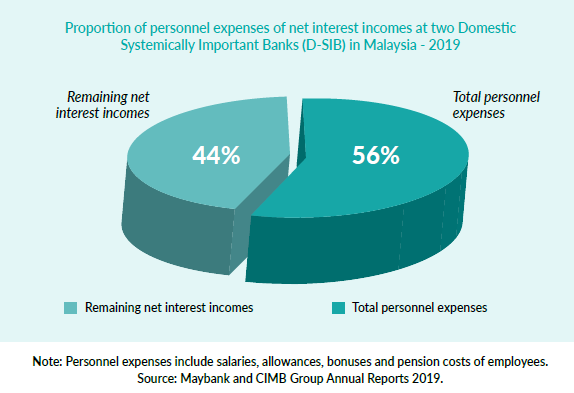

In reality, interest incomes earned by banks are more than enough to provide lucrative remuneration to their employees, which are often a small segment of a population. For example, the combined net interest incomes of two Domestic Systemically Important Banks (D-SIB) in Malaysia for the financial year ended in 2019 was more than RM22 billion, as reported in their publicly available annual reports.

Total personnel expenses reported for these two banking groups, Maybank and CIMB Group, for the same year was more than RM12 billion, which is greater than 50% of the combined net interest incomes cited above. Personnel expenses include salaries, allowances, bonuses and pension costs of their employees. These are government-linked entities with about 78,000 staff in combination.

As a benchmark, Malaysia is populated by more than 30 million people. The mean income of B40 (bottom 40% income group) was RM2,537 in 2014. If the average pay per employee at the two government-linked banking entities is more than RM12,000 per month (i.e. RM12 billion / 78,000 / 12 months), then how do we tolerate this wide pay gap especially during the outbreak of COVID-19 that has presumably hit the B40 harder?

Although the above estimation is constrained by limited publicly available information, this simple analysis suggests that the government-linked banks and what can be regarded as their well-paid workforces are presumably afforded with the financial capacity to share more during these unprecedented financial circumstances than many. This is a particularly serious call to those with socially excessive pay amounts (if any). A bank’s CEO that was awarded more than RM8 million in remuneration last year is no exception.

Socially responsible banks (Islamic and non-Islamic) may consider redistributing at least half (if not all) of their accrued and actual net interest incomes to help people in greater need, though this means halving the remuneration of well-paid staff and directors. On this note, those on higher pay scales are supposedly taking greater social responsibility to forgo greater amounts from their remuneration packages.

Although pay cuts amongst elites are becoming a new normal, one may argue that taking a temporary salary cut is not enough because perks, benefits and unjustifiable variable pay in combination can form a significant part of their remuneration packages. More is expected from the banking system and bankers in sharing their prosperity during this time of need. Forgoing or redistributing interest incomes or profits on loans to help those worst affected and in greater need due to the economic implications of COVID-19 should be encouraged. There are abundant opportunities for highly-paid bankers to walk the talk on shared prosperity, which is not inconsistent with the spirit underlying Islamic finance.

Although ‘free lunch’ may not exist but Muslims are guided by Verse 280 of Surah Al-Baqarah that states: “If, however, [the debtor] is in straitened circumstances, [grant him] a delay until a time of ease; and it would be for your own good – if you but knew it – to remit [the debt entirely] by way of charity.” This prescription is available universally to address the financial and economic implications of COVID-19.