‘Indeed, with every difficulty, there is a relief’ (Quran: 94.6)

The USD2.19 trillion Islamic finance industry, represented by almost 1,400 institutions worldwide (IFSB, 2019)1 faces unprecedented challenges driven by the global COVID-19 pandemic. It is expected that the current pandemic will gradually result in an extraordinary economic recession, second only to the Great Depression. The decline of world GDP is estimated to be 3% in 2020, with an accumulated loss of USD9 trillion, greater than the economies of Japan and Germany, combined (IMF, 2020)2. This has created a set of challenges for all types of financial markets including the Islamic financial services industry. One impact could be the 2.17% GDP decrease in 12 countries, which represents 87% of the world’s Islamic finance assets in the GCC, Southeast Asia, South Asia, Africa, and the Central Asia. S&P Ratings projected a 62% drop in the Sukuk issuance from USD162 billion in 2019 to USD100 billion in 2020 (Hidayat, Farooq, and Alim, 2020)3. It indicates a severe negative impact with far-reaching implications on the Islamic banking industry leading to possible bankruptcies and layoffs.

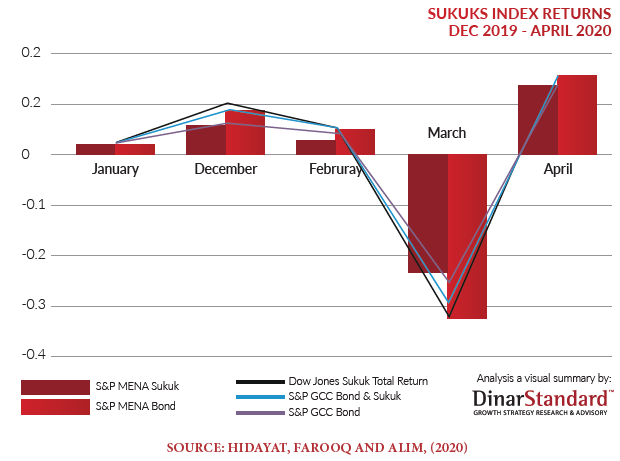

SUKUK IMPACT

Returns from five sukuk and bond indexes (Dec 2019-April 2020) show the COVID-19 impact realized in March. S&P Ratings projected sukuk issuance is expected to drop from USD162 billion in 2019 to USD100 billion in 2020.

The pandemic is a whole new breed that is much darker than a “black swan”, which has been emerging not only as a global health threat to human life and a strain on the international economy, but also creating fear and chaos that prevent us from making the right decision at the right time. Therefore, cognitive awareness and the ability to make sound, efficient, and effective decisions (the Smart Decision) are imperative, particularly during this critical time where the crisis has forced Shari’a scholars and Islamic finance leaders to quickly make decisions that involve difficult tradeoffs.

Shari’a provides a set of articulated strategic values that guide the leaders in making critical decisions. When a seemingly profitable strategy violates a core Islamic value, the solution is not to abandon the value, but to find a better strategy that allows for the fulfilment of both aims. Decisions shape an organisation’s behaviour and determine its future direction. A mediocre choice probably would not affect the organisation and its shareholders alone, but will certainly have negative consequences for all its stakeholders i.e. consumer, employees, public, and the environment.

Establishing a clear set of decision-making parameters can help Islamic banking leaders steer their organisations through crisis and beyond. This article highlights Shari’a insights and outlines the parameters and psychological techniques for making smart Shari’a decisions in the Islamic banking business during this unprecedented crisis. Shari’a decision-making (SDM) refers to a consultative exercise conducted by qualified Islamic finance professional/s to identify (1) a Shari’a-compliant and economically viable solution to a problem faced by the organisation, (2) with a systematic course of action that is also in line with the Shari’a. SDM is an end-to-end control framework to minimise the possibility of a decision that may undermine the Shari’a validity of the relevant product, service, or operation.

THE JURISPRUDENCE OF PANDEMIC (FIQHUL JAWĀEH)

Sanctity of Islamic Law of Contract obliges the parties to honour their obligations arising from the contract (Kamali, 2005)4, and disclosure of information to reduce the risk of asymmetric information is a moral hazard. This is firmly entrenched by virtue of the divine injunction that states, ‘O you who believe! Fulfil all contractual obligations’ (Qurʾān, 5:1). However, in exceptional cases and unpredictable events, the responsibilities may not be upheld when the performance of a contractual obligation becomes excessively onerous.

It is narrated that the Prophet (PBUH) ordered value discounts due to calamities (Ibn Al-Ḥajjāj, Muslim, Hadīth No. 3004)5. By analysing similar narrations, the contemporary Muslim jurists developed the ‘pandemic theory’, which, with some differences, resembles the concept of force majeure and emergency circumstances in legal theory. The principle of ‘pandemic theory’ finds its basis in Islamic jurisprudence in the principle of ‘excuses’ (al-aʿzār) in the Hanafi literature and ‘pandemic’ (al-jawāeḥ) in the Malikī and Hanbalī school of thought (Al-Zahab, 2011)6.

The scholars are also of the view that in light of the principles derived from the Prophetic narration about the impact of a pandemic on fruit trade, the same principles can arguably be applied to other contractual transactions such as manufacturing, construction, and general trade contracts where a pandemic causes a hardship. Nonetheless, for an event to qualify in Islamic law as a pandemic, it shall be (1) an unanticipated catastrophe (2) beyond the control of the contracting parties (3) not caused by human, (such as natural disasters flood, earthquake, pandemic, etc.), or caused by a human without the possibility of indemnity by the doers, (such as fires, explosions, wars, revolutions, and terrorism; changes in laws, and embargoes) that (4) interrupts the expected course of events and prevents participants from fulfiling their obligations (Al-Dusry, 2020)7. Depending on the degree of the pandemic’s impact on the party’s ability to perform its contractual obligations, the contract may be revoked if its commercial purpose is frustrated, or only some of its terms may be renegotiated to relieve a customer’s financial distress.

‘O you who believe! Fulfil all contractual obligations’ (Quran: 5:1)

THE PARAMETERS FOR MAKING SMART SHARI’A DECISIONS AMIDST COVID-19

The scholarship on pandemic theory reveals that in an unprecedented time like COVID-19, the Shari’a decision-making in financial transactions shall be governed by certain parameters (Al- Sayyari, 2020)8. The below parameters in Table No. 1 should be considered keeping in view the Islamic bank’s relationship with its shareholders, depositors, and customers. The management of the bank is entrusted with two responsibilities; (1) an agent of the shareholders and depositors, (2) a fund provider to the customers. As far as the second relationship is concerned, it could be either in the form of the seller and buyer (murābaḥah, salam, istiṣnāʿ), or lessor and lessee (ijārah), or a partnership (mushārakah and muḍārabah) or agency (wakālah).

TABLE NO. 1:

THE PARAMETERS FOR MAKING SMART SHARI’A DECISIONS AMIDST COVID-19

Ibn al-Qayyem stated that in Shari’a, the commercial contracts are primarily based on the principle of justice that requires equilibrium of rights and liabilities to ensure fairness and transparency in the financial dealings (Al-Jauziyyah, 2002)9. Principally, the sanctity of contract shall be honoured by the parties, however, when a pandemic like COVID-19 disrupts the contractual equation, the principle of justice equally necessitates to alleviate extraneous obligations as the hardship events create a burden on one or both of the contracting parties. This is manifested by the Prophetic narration: “If you sell some fruit to your brother and it was struck by blight, it would not be lawful for you to take anything from him. How can you take your brother’s money unjustly?” (Muslim, Hadith No. 855).

In the context of Islamic banking, given the devastating economic impacts of the COVID-19, the Shari’a decision-makers should uphold justice from two perspectives, (1) in the relationship between the bank and its customers and clients (liability side), and (2) between the bank and its shareholders and depositors (asset side). Following suggestions may be helpful:

- On the liability side, the Islamic banks should pass on the benefit of reduction in the policy rate, if any, to the customers in existing and new facilities.

- For an appropriate treatment of the receivables, the attention should be given to the source of a receivable whether it is generated from a sale contract or lease or partnership. Further, it is also important to identify the current stage of the facility i.e. advance, inventory or financing. The SBP (State Bank of Pakistan, 2020)10 regulatory relief to dampen the effect of COVID-19 on Islamic banks may serve as a guiding principle. The below chart is part of the SBP guidelines:

ISLAMIC BANKING MODE WISE GENERAL PRINCIPLES

MODE

1. MURABAHAH/MUSAWAMAH (WHERE BANK IS SELLER)

- In transactions where Murabahah/ Musawamah (declaration/offer & acceptance of Murabahah) is not yet executed

- In transactions where Murabahah/ Musawamah has been executed

MODE

- Murabahah/Musawamah price along with tenor may be increased at declaration i.e. the time of execution (offer and acceptance) of Murabahah/ Musawamah Contract.

- Additional profit cannot be charged on deferred principal/profit as Murabahah/Musawamah price cannot be increased. However, a separate transaction based on Tawarruq/ Commodity (Murabahah/Musawamah)/ Salam/Istisna/Diminishing Musharakah/ Running Musharakah, etc. may be executed with the customers to settle the Murabaha receivable.

2. SALAM/ISTISNA/MUSAWAMAH (WHERE BANK IS BUYER)

MODE

- In transactions where the customer has not yet delivered the goods to the bank

- In transactions where the customer as an agent of the bank has not yet sold the goods onward

- In transactions where the customer as an agent of the bank has sold goods onward

MODE

- Delivery may be extended along with the extension in tenor and increase in the selling price of the goods in a subsequent sale.

- Tenor may be extended, and additional profit may be charged through increased selling price.

- Tenor may be extended to the extent where incentive of the customer may be reduced to ‘Zero’ after which charging additional profit due to extension in tenor is not allowed. However, a separate transaction based on Tawarruq/Commodity Murabahah/ Musawamah/Salam/Istisna/Diminishing Musharakah/Running.

3. DIMINISHING MUSHARAKAH (SHIRKAT-UL-MILK)

MODE

- Principal deferment

MODE

- Unit sale/purchase may be deferred, and tenor may be extended, accordingly on which additional/adjusted rent may be charged.

4. IJARAH

MODE

- Principal and profit deferment

MODE

- Rentals may be deferred (fully/partially) along with charging.

5. MUSHARAKAH

MODE

- Inclusive of Running Musharakah

MODE

- Tenor may be extended and terms & conditions of Musharakah/Running Musharakah may be revised.

- Since the bank’s cash streams will be disrupted by the “moratorium” imposed by majority regulators, a regulatory relief to the banks in the form of a decrease in cash reserve requirement (CRR) and capital adequacy ratio (CAR) may resolve some of the liquidity issues.

Scholars consider prevention of harm to be half of the Shari’a in that all its rulings are enacted by the Lawgiver to either secure benefit (maṣlaḥah) or prevent harm (mafsadah). The Prophet ((PBUH) said that harm shall neither be inflicted nor reciprocated (Bin Hanbal, Musnad Ahmad, Hadith No.2748)11. This narration has become a fundamental maxim in financial decision-making. The outbreak of pandemic COVID-19 has undoubtedly disturbed the financial architecture of the whole world causing economic harm that adversely affects contractual obligations. Therefore, the Shari’a decision-makers should assign a greater value to this maxim to minimise the negative impacts of the pandemic in light of the Prophetic narration to provide relief in calamities. This needs a thorough analysis with due consideration to the individual cases. Some cases might need amendments in the contracts, while others might be terminated. The detailed guidance is provided in the AAOIFI Shari’a Standard No. 36: Impact of Contingent Incidents on Commitments.

For the implication of this maxim, the decision-makers should ensure first, that the pandemic is indisputably harming one or both parties, since “no consideration is given to illusion” in Shari’a. In other words, the possibility of harm should be greater than its absence. Second, the harm must be excessive, as not all businesses are critically affected. In fact, some businesses have grown due to the pandemic. Below are some suggestions to prevent harm:

- Provision of relief in terms of moratorium,

- Easing the requirements of security and pledge placement,

- In case of default, postponement of confiscation of the customer’s security who is affected by the pandemic,

- Postponement of the agreement clause of “all outstanding to become due” in case of delay in payment,

- Inactivation of charity clause,

- For customers who are facing genuine cashflows issues, the bank may offer restructuring facilities to settle the previous debt with certain conditions as described in the SBP guideline.

- To compensate the depositors and shareholders loss, the bank may opt for debt to equity swap with corporate customers or converting debt into muḍārabah Capital (Hasan, Haron, and Muhammad, 2018)12,

- Provision of sovereign guarantee against the customers’ financing.

The upholding of justice and prevention of harm in its all forms are subject to a fundamental principle that the decision shall not lead to usurpation of wealth (ak lul māl bil bāṭel) strictly prohibited in Qurān (2:188). This includes all types of income earning method that violates the explicit Shari’a injections where profit is generated without counter value, regardless of the mutual consent of the parties. The Prophet (PBUH) particularly emphasised on avoidance of usurpation as he said in the pandemic narration: “How can you take your brother’s money unjustly”? Therefore, the decision-makers shall observe ‘avoidance of wealth usurpation’ as an objective measure to determine the Shari’a implication of the relief decisions made in favour of the bank and its customers. Following are some of the decisions that lead to usurpation of wealth in Islamic banking:

- Debt restructuring with an extension of maturity that results in an additional amount to be paid without entering into a new contract,

- An enforced restructuring of insolvent’s debt with an increase in the outstanding (Hasan, Haron, and Muhammad, 2018),

- Channelling profit to the depositors and shareholders without actual investment activity.

As the COVID-19 outbreak unfolds, ensuring the public interest (maṣlaḥah ʿāmmah) takes priority in the hierarchy of Shari’a decision-making. In fact, in Islamic jurisprudence, the maṣlaḥah is deemed as a secondary source of law to accommodate social development, cultural changes, and communal need. Maṣlaḥah refers to a consideration securing a benefit or preventing harm, provided that it is harmonious (wasf mulā’em) with the objectives of the Lawgiver, and the Shari’a does not indicate its validity or otherwise (Badran, 1969)13. The Companions, for example, decided to issue currency, to establish prisons, and to impose a tax (kharāj) on agricultural lands in the conquered territories even though no textual authority could be found in favour of these initiatives (Khallaf, 1990)14.

Maṣlaḥah is one of the most promising doctrines in Shari’a decision-making for dealing with the crisis. It creates ease and gives Islamic finance space for flexibility to survive, coexists, and carry out its value-driven mission for the benefit of Ummah. However, the consideration of maṣlaḥah shall be governed by the parameters prescribed by jurists. This is to ensure that maṣlahah is actualised on the Shari’a guidance, not merely based on the outcome of social studies or the deduction of an individual intellect (Laldin, 2010)15. The following parameters are placed by the International Islamic Fiqh Academy:

I. The maṣlaḥah should be genuine, and not imaginary,

II. It should be holistic, and not partial,

III. It should be public, and not private or special,

IV. It should not thwart a superior or similar maṣlaḥah,

V. It should be in harmony with the maqāṣid al-Shari’a (Shari’a objectives).

In the context of Islamic banking, this responsibility primely rests upon the shoulders of regulators. The following regulatory initiative and support measures as suggested by Chattha (2020)16 may ensure maṣlaḥah in the Islamic banking industry during COVID-19. The regulatory authorities should:

- maintain a reasonable level of prudence between preserving the safety and soundness of Islamic banks, maintaining financial stability, and supporting economic activity. Supervisors and other relevant authorities may consider relaxing regulatory capital requirements and macro-prudential buffers to reduce the impact of the COVID-19 shock on the economy,

- in dual banking systems, they should ensure regulatory transparency and clarity of their various regulatory and regulatory interventions in the market while safeguarding a level playing field for Islamic banks,

- assess a broad range of liquidity risk factors of Islamic banks to mitigate the COVID-19 impact. Supervisors should consider reducing the liquidity requirements under various liquidity tools such as the LCR, NSFR, liquidity ratio, and statutory reserve ratio, and should continue to monitor the banks’ liquidity situation. Central banks should provide Shari’a-compliant liquidity support and LOLR facilities to Islamic banks,

- should provide support for issuing sovereign Sukūk as part of a government strategy of diversification of financial instruments for financing fiscal deficits,

- should review and ensure the financial safety nets such as the provision of Shari’a-compliant deposit insurance (SCDIS) and a Shari’a-compliant lender-of-last-resort (SLOLR) scheme, as well as an insolvency regime for Islamic banks.

PSYCHOLOGICAL TECHNIQUES

As the pandemic unfolds, the need for smart decisions to be made on spot has increased. Nonetheless, when a strong emotion of fear, uncertainty, and anxiety starts to cloud on the skyline, the human brain struggles to make the right choice and more often ends up with an unfortunate one. It is observed that people in highly stressful situations focus their attention so tightly on the decision/present scenario in front of them that they miss vital new information, a phenomenon called ‘cognitive tunnelling’. For example, they may become so fixated on balancing a technical equation during a tens event that they fail to notice the long-term consequences of their decisions.

It is also evidenced that the decision-makers often become captive of the scenario presented to them by the management. A good solution to a well-posed problem/question is probably a smarter choice than an excellent solution to a twisted one. Hence, framing a question is not only a governance issue, but it also has Shari’a implications. Therefore, in a hadith, the Prophet (PBUH) categorically stated: maybe someone amongst you can present his case more eloquently and convincingly than the other, and I give my judgment in his favour according to what I hear. Beware! If ever I give (by error) somebody something of his brother’s right, then he should not take it as I have only given him a piece of fire (Al-Tabrizi, Mishkat, Hadith No. 638)17.

There is no guidebook on which decisions to make, nevertheless, there is an established body of evidence on how to make them. Psychologists found that certain cognitive biases impair the ability to make smart decisions during a crisis (Mahoney & DeMonbreun, 197718; Plous, 199319). Avoidance of the following psychological biases may ensure the soundness of a Shari’a decision (Agha, 201820; Agha and Malik, 201921).

STAGES OF SHARI’A DECISION MAKING

- CONCEPTION (AL-TASWĪR)

It is the first stage of the Shari’a Decision Making process. During this stage, the management presents the issue to the Shari’a advisory board (SAB). Before making a single observation, scholars should be aware that they may be subject to psychological impacts while collecting and processing information (Furber, 2012)22.

For example,

- The way an issue is presented to the SAB may influence the potential Shari’a verdict that the SAB comes up with (Framing Impact),

- The first information received may have a greater impact than the subsequent information (Anchoring Impact),

- The first thing they learn about a professional/institution either positive or negative will likely let them assume that the person/institution possesses other positive or negative attributes (Halo and Reverse-halo Impact),

- The scholars should be aware that the management may try to present their case in a way that shows themselves in the best positive light (Self-serving Bias) while underestimating the external and internal factors,

- Management may exhibit themselves as victims of the circumstances while assuming that the mistakes of others are intentional or due to personality traits (Fundamental Attribution Error),

- The prior knowledge/experience of the scholar or the issue presenter may impact their understanding of a new case (Availability Impact).

VULNERABILITY TO PSYCHOLOGICAL IMPACTS

- Framing Impact (a cognitive bias where a person’s decision is affected by the way the information about the decision is presented to him).

- Anchoring Impact (the tendency to rely heavily on the very first piece of information received).

- Halo Impact and Reverse-Halo impact (the tendency for positive or negative impressions of a person, company, brand, or product in one area to positively or negatively influence one’s opinion or feelings in other areas).

- Self-serving Impact (the tendency to perceive oneself in an overly favourable manner).

- Fundamental Attribution Error (an individual’s tendency to attribute another’s actions to their character or personality, while attributing their behaviour to external situational factors outside of their control).

- Availability Impact (a mental shortcut that relies on immediate examples that come to a given person’s mind when evaluating a specific topic, concept, method or decision).

2. ADAPTION (TAHQĪQUL MANĀT)

STAGES OF SHARI’A DECISION MAKING

During this stage, the SAB matches the relevant features of the newly presented case to the known legal case in Islamic jurisprudence that corresponds best to the newly described case. The scholar needs to keep in mind that:

- When looking for the corresponding issue, he might be influenced by his previous experience/knowledge, or frequent cases, or presenter’s identification and judgment of the issue in the previous stage (Availability Impact).

- Similarly, an inclination to a particular feqhi text, an initial impression, estimate, or idea may have an oversized impact on subsequent thoughts and judgments (Anchoring Impact).

VULNERABILITY TO PSYCHOLOGICAL IMPACTS

- Availability Impact

- Anchoring Impact

- EVALUATION (AL-TAHLĪL)

STAGES OF SHARI’A DECISION MAKING

During this stage, the SAB checks whether the pre-conditions (shurūṭ), essential elements (arkān) for the issue identified in the previous stage, have been met in the newly presented case. Finding few or none of these in the new case is a good indication that the scholar should go back to the stage of adaption. At this stage,

- A scholar sometimes become overly confident in his initial decision (Overconfidence Impact) and instead of moving back to the adaption stage, proceeds to the response, or

- Instinctively follows other scholars’ view without proper Shari’a due diligence (Status-Quo Impact).

VULNERABILITY TO PSYCHOLOGICAL IMPACTS

- Overconfidence Impact (when a person’s subjective confidence in his or her judgments is reliably greater than the objective accuracy of the judgments, especially when confidence is relatively high).

- Status-Quo Impact (preference for the current state of affairs).

4. RESPONSE (AL-IFTĀ)

STAGES OF SHARI’A DECISION MAKING

It is the final stage in the Shari’a decision-making process. At this stage, the scholar re-examines the presenter’s circumstances to ensure that applying the ruling will realise the presenter’s interests (maṣāliḥ al-mustaftī) without violating the overall objectives of the Shari’a (maqāṣid al-Shari’a). Several flaws in the decision-making that arise here are likely to result from errors that occurred at earlier stages in the process. However, since this stage focuses on searching for consequences and the likelihood of their occurrence, the scholar needs to take note of probability and Status-Quo related impacts. For example,

- The scholar should be aware that the ease in which a consequence is imagined is not related to the likelihood of its occurrence, (Overconfidence Impact),

- The scholar must not be influenced by exaggerated claims of financial loss by the management on account of disapproval of a certain product/service (loss Aversion Impact),

- The management is likely to view themselves as victims of circumstances while assuming that the mistakes of others are intentional or due to personality traits (Fundamental attribution error),

- Managerial influence – where the management displays a strong bias in favour of a specific solution to an issue because it intends to maintain the status-quo of existing practice/ features of existing product or service or the management manifests resistance against new initiative (Status-Quo Impact),

- Scholarly reputation – where a product or service is approved by a reputed Shari’a scholar. It becomes a challenge for junior Shari’a scholars to question it or suggest an alternative due to the reputation of those who endorsed it (Status-Quo Impact).

VULNERABILITY TO PSYCHOLOGICAL IMPACTS

- Overconfidence Impact.

- Loss Aversion Impact (a cognitive bias that suggests that for individuals the pain of losing is psychologically twice as powerful as the pleasure of gaining).

- Fundamental Attribution Error.

- Status-Quo Impact.

CONCLUSION

The COVID-19 outbreak continues to wreak havoc on economies across the globe and threatened the stability of the global financial system. Islamic banking authorities are pursuing unprecedented regulatory measures to mitigate the impact of the outbreak. It is in such times of uncertainty that the torch of Shari’a-driven insights can navigate us towards an efficient response and smart decision enabling the Islamic banking industry’s resilience, underlying mission, financial success, and excellence in the post-COVID-19 era. It might be a blessing in disguise for the Islamic financial institutions to exhibit how firmly they stand with their principles and raison d’etre of being a just and compassionate financial system. This is also an opportunity for the industry to carefully carve its branding and distinctiveness by becoming the prominent and leading agent of positive change for the whole financial system, and to operate within a network economy that is built upon shared values of integrity, responsibility, inclusivity, and sustainability.