The renowned British-born American author wrote an interesting book “Start with Why”, which has been an eye-opener for various professionals, policymakers and organisations alike. The book is an excellent read and reminds organisations to pause and reflect on what they offer, what is the mere purpose of their existence and why should anyone care. He further states that all organisations usually know what they offer, few of them know how they offer what they offer, while very few can clearly state why they do what they do. The latter is clearly what most of the stakeholders really care about.

This article will re-emphasise the important role that the three infrastructure bodies related to standards-setting, the Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Finance Institutions (AAOIFI), the Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB) and the International Islamic Financial Markets (IIFM), have been playing in the development of the Islamic banking and finance industry.

STANDARDISATION

Standardisation is the process of developing standards based on the consensus of various stakeholders of an industry. Standardised guidelines are used to create products and services that are of consistent quality, uniform practices and meet the need of the industry. Standardisation focuses on the product creation process, operations of businesses, technology in use, and how specific compulsory processes are instituted or carried out. Various stakeholders involved in the standardisation processes include customers, governments, regulators and supervisors, corporations, and standards-setting organisations.

Standardisation happens across all industries throughout the world when organisations wish to achieve a consistent level of quality, production standards, manufacturing output and brand image. To relate with examples, one can draw parallels from everything that is around: from food to technology, engineering to health care and finance to education; all of them follow standardisation. In the food industry, a McDonald’s Big Mac or an apple pie has been standardised to such an extent that every time a customer buys he knows what to expect, this creates brand recognition. In the engineering industry, equipment such as air conditions, plugs and sockets are made in such a way that all products in the same category are created to the same specification between different companies. In terms of a measurement scale, a metre, litre, or kilogram is defined in the same way throughout the world. Similarly, in the education sector, the learning objectives from a GCSE class have been standardised to ensure all students are following a set of standardised practice globally. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) is an independent, non-governmental international organisation, which has issued more than 23,000 standards in almost all industries ensuring safety, efficiency, reliability and quality of the products and services. The scope of standardisation includes steps and actions that ensure consistency, uniformity and conformity in the definitions, terminologies, formats and methods used to produce products and offer services.

The assets of Islamic banking and finance industry have reached USD2.591 trillion according to the Global Islamic Finance Report 2019. Although this still accounts for only a per cent of the global finance industry, it is a still a significant size when we relate it to the birth of the modern Islamic finance industry in the 1960s and 1970s. During the social banks’ attempts in Egypt (1960s), Tabung Haji (1963) was set up in Malaysia with an aim to help Malay Muslims save gradually for their Hajj expense. In 1975, The Islamic Development Bank (IsDB), a multilateral development bank and Dubai Islamic Bank, the first commercial Islamic bank were setup. In the following years more and more Islamic banks, takaful companies and academic institutions emerged in various countries around the world. Countries like Pakistan, Iran and Sudan announced their intentions to transform their economies to being fully Shari’a-compliant, while other countries decided to allow both conventional and Islamic financial system to operate within the existing framework offering stakeholders the option to choose. The Islamic Research and Training Institute (IRTI) was established by IsDB in 1981 while other multilateral institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank published working papers and articles on the Islamic banking and finance industry.

As such, the Islamic finance industry has progressed in different parts of the world with the help of diversity and flexibility in the application of fiqh opinions. However, there was a risk that soon this diversity in opinions may become a constraining factor if the challenges arising are not properly recognised and managed especially at the global level. Further, the concern introduces the possibility of Shari’a arbitrage, which may create temptation of enhancing commercials and profits at the cost of the spirit of Islamic finance and disturb market disciplines. Lastly, discretion within the market participants need to be controlled and supervised to ensure that it is not abused and give birth to a loss in confidence by the customer. This gave rise to a call from the regulators for robust regulations and supervisions of Islamic financial institutions, giving rise to the need for standardisation of practices.

THE NEED FOR STANDARDISATION IN ISLAMIC FINANCE

There have been various attempts in the past to reconcile the views of various scholars, standardise their rulings on different issues and develop unified rulings for people to follow. However, such attempts failed in the past as it was difficult to compel people to accept one opinion or a single school of thought, as a result, diversity prevailed.

Some of the common advantages of standardisation in the context of Islamic banking and finance industry include:

- Uniformity: With the development in Islamic banking and financial institutions, there was not a single authority to guide institutions in Shari’a-related matters, as a result, institutions felt the need to set up their own Shari’a boards to receive guidance and clearance on the underlying transactions and products. However, with the rapid development of the industry and such Shari’a boards, there was an increase in the diversity in Shari’a ruling in fiqh opinions. This developed a strong need for these Shari’a opinions to be unified and harmonised to ensure that there are clear processes and best practices prescribed for the industry to flourish. If we are to relate the conventional financial world in terms of accounting practices, there are two well-known practices; the United States Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) and the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) – the former is rule-based while the latter is principle-based. Since 2002, a convergence project has been initiated between the two sets of standards with the objective to eliminate differences and bring further uniformity for the benefit of the global industry. The need within the Islamic finance industry is similar where the practices need to be unified to bring better clarity, transparency and comparability among different practices.

- Efficiency: Standardisation creates a road map of best practices, which can be easily followed by different stakeholders including the new entrants in the industry. For example: if a conventional bank wants to convert to an Islamic bank, then clear processes should be available for the bank to follow. These best practices should be the ones that are globally understood and agreed upon, so it makes it efficient by saving cost, time, and effort for the new entrant instead of developing something from scratch – this is one of the ways standardisation adds value.

- Reputational Risk: The greatest threat to the future of the global Islamic finance industry is the ‘reputational risk’, defined as that which ‘arises from negative publicity or perception associated with the activities of an Islamic financial institution by the industry investors and customers’. This risk can be caused due to multiple reasons such as; poor levels of compliance with Shari’a; non-compliance with Shari’a; unethical practices; or conflicting fatwas (opinions) of Shari’a scholars sitting on Shari’a Supervisory Boards of different organisations in different parts of the world.

It is quite possible to have different fatwas on the same product. Even if two conflicting fatwas are acceptable, it will nevertheless have the potential to create a negative perception in the minds of investors and customers, which will only impede the industry’s penetration and growth. For example, the fatwas on Tawarruq-based deposits, Mudarabah-based or cooperative (Ta’awuni) Takaful, Bai Inah, Islamic credit cards, etc., are seen to be controversial in one jurisdiction but acceptable in another. These cross-jurisdictional differences leading to a wrong perception are a major threat to the future of Islamic finance. Moreover, just because a fatwa is acceptable, it does not automatically mean that it serves the overall Maqasid of Shari’a as well. In fact, we are all conscious of the fact that certain fatwas issued on the basis of darura (necessity) or Maslaha (public interest), which are although technically Shari’a-compliant may serve short-term objectives and cannot be generalised and used on a long-term basis. To relate an example; Vedanta Resources, a diversified metals and mining company from India listed on the London Stock Exchange and a part of the FTSE 100 index and the FTSE Shariah Index UK was found to be seriously violating ethical practices i.e. violations of human rights and environment. As a result, the Norway Government Pension Fund divested the stock from the fund, yet it remained part of the FTSE Shariah Index UK. Here the stock may be Shari’a-compliant, but it does not fulfil the objectives of Shari’a, giving rise to an important question that how can such a company can be part of a Shari’a-compliant portfolio.

- Acceptability at Global Level: furthermore, it was evident that the Shari’a boards at individual institutions cannot be regarded as the highest authority as the corporate governance between them and the board of directors of the institutions they advised is questionable.

With regard to the Islamic financial institutions, they were following the conventional standards issued by the International Accounting Standards Committee (IASC) or GAAP, it was realised that the transactions do not capture the real nature of the Shari’a-compliant transactions. Although a number of such issues can be resolved by a regulatory body enforcing standards and practices at a national level, it is much difficult at a global level. Additionally, various challenges arose in terms of recording (accounting), reporting and auditing of Shari’a-compliant transactions. For example, the recording of Murabaha transaction was different in various countries, some (Bahrain and Kuwait) would do it on an accrual basis, while some based on cash (Malaysia and Sudan), which created discrepancies in terms of comparability among different markets. As a result, a strong need was felt for an independent body to be set up to ensure that best practices and standards are developed for the global Islamic banking and finance industry. Standardisation at a global level enhances trust and confidence of all stakeholders (including clients, regulators, investors and suppliers) in the practices of Islamic finance, which can then be compared cross-jurisdictionally.

- Human Talent: one of the critical challenges facing the Islamic finance industry is the availability of adequately and rightly trained human talent. Standardisation of the industry assists in the development of capacity that is well-trained, understand the processes, rules and regulations as well as product and services. Such talents possess skills and knowledge that can be exported and applied to different industries

globally.

- Unprecedented Times: The need for standardisation has always been there but the unprecedented times of COVID-19 have reemphasised the importance of it. These times have given rise to situations that were not expected otherwise and thus require guidance. If we are to relate with examples:

- From a Shari’a perspective, if you have receivables, you cannot build further profit on it or discount them, however, we have seen fatwas permitting discount and additional profit on receivables due to moratoriums introduced by the regulators. Furthermore, we have also seen examples where penalty funds have been allowed to be recognised as an income and cover the loss generated from financings. However, the rulings from Shari’a and standards-setting bodies are clear on this. The only solution to this is standardisation by an independent institution based on the opinions and Ijtehad of jurists from different Madhahibs.

- In accounting, according to IFRS 9, there is Day 1 loss on moratoriums, but Islamic finance works differently. In Islamic finance, it is not allowed to add more profit, while it may not be fair and equitable if the institution suspends amortisation of the deferred profit for the period of moratorium or records an upfront loss.

- Islamic finance is rated like a conventional institution merely taking credit risk, however, these times of market downturn has allowed us to contemplate that Islamic finance has underlying assets, and should be rated accordingly. AAOIFI has issued a standard on Shari’a compliance and fiduciary ratings that tackle all of this. Faysal Bank in Pakistan has opted and is the first bank to be rated based on the new standard issued by AAOIFI in collaboration with the International Islamic Rating Agency (IIRA).

Individual IFIs do not possess the capabilities required for such situations, further, each IFI may come up with an individual response, which may not be holistic in nature and give rise to different practices. Standards-setting bodies like AAOIFI, and the Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB) have issued guidance for jurisdictions following their standards. Further, the standards issued by them appeared to be resilient and were able to take care of the situation during these times.

Since 1991, there are a number of different infrastructure organisations set up for the development of the Islamic banking and finance industry, however for the purpose of this article in the next section, the role of only three institutions related standards-setting is discussed.

THE NEED FOR STANDARDISATION IN ISLAMIC FINANCE

Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI)

In 1989 a number of Islamic financial institutions, such as the Islamic Development Bank (IsDB), Dallah Al Baraka, Faisal Group (Dar Al Maal Al Islami), Al Rajhi Banking and Investment Corporation, Kuwait Finance House and Albukhary Foundation signed an agreement to set up an autonomous not-for-profit body, the Financial Accounting Organization for Islamic Banks and Financial Institutions (FAOIBFI) that prepares accounting standards in compliance with the Shari’a principles for Islamic financial institutions globally. The organisation started operations in 1991 and Professor Rifaat Ahmad Abdul Karim was selected as the founding Secretary-General. Soon after the establishment of FAOIBFI, its mandate was expanded to include Shari’a, auditing, governance and ethical standards, as a result, the name was changed to Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI).

At present, there are 114 standards and technical pronouncements in issue in the respective areas, which are all interlinked with each other to form a bouquet or a package of standards for the regulators trying to protect and enhance the integrity of the respective Islamic finance industry. Thus, these standards, collectively, offer regulators, as well as Islamic financial institutions, the direction they need, to ensure that compliance level with Shari’a is high and that they are following the highest benchmark in best practices.

The aim of AAOIFI and its standards in this regard is to achieve conformity or similarity – to the extent possible – in concepts and applications among the Shari’a supervisory boards of Islamic financial institutions to avoid contradiction and inconsistency between the fatwas and the applications by these institutions. The standards issued by AAOIFI are principle-based and not rule-based.

AAOIFI standards are adopted and adapted in various capacities around the world in no less than 28 jurisdictions. In terms of full adoption of at least one set of standards, there are 22 countries and 24 jurisdictions where AAOIFI accounting standards are adopted followed by Shari’a in 13 countries and 19 jurisdictions while the Governance standards are adopted in 10 countries and 18 jurisdictions.

Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB)

In the late 1990s, the Islamic finance industry was developing as an important channel of financial intermediation where conventional institutions started venturing into this space, there emerged a regulatory and supervisory need to address the unique underlying principles and philosophy, which also shaped its financial transactions and risk profiles. These unique risks require a separate regulatory framework to provide for their effective assessment and management. This in turn would contribute to the development of a robust and resilient financial system that can preserve financial stability and contribute to effective growth and development. In this regard, a proposal was endorsed during the IMF-World Bank Annual Meetings in Prague by a group eight Central Bank governors and officials from IsDB, the AAOIFI and the IMF in the year 2000 to set up an independent institution. The IFSB was mandated to develop a uniform set of prudential, supervisory and disclosure standards for the Islamic financial services industry. In doing so, the IFSB would assess to what extent it needs to adapt to the international best practices on risk management as well as the development of new risk management techniques in compliance with the Shari’a principles. In this regard, IFSB would complement the work of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS), the International Organization of Securities Commission (IOSC) and the International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS).

| Full Adoption | Countries | Regulatory Jurisdictions |

| Shari’a | 13 | 19 |

| Accounting | 22 | 24 |

| AGEB* | 10 | 18 |

Since the establishment of IFSB, it has issued no less than 22 standards, 3 technical notes, 7 guidance notes and 14 working papers. These standards are adopted by the jurisdiction on a select and voluntary basis.

Between the IFSB and AAOIFI, IFSB has the strongest membership support with 189 members, which include 79 regulatory and supervisory institutions, 9 international inter-governmental organisations and 99 financial institutions, advisory firms and stock exchanges from about 57 jurisdictions.

International Islamic Financial Markets (IIFM)

Bahrain has and continues to play an instrumental role in the development and standardisation efforts of the global Islamic banking and finance industry. After hosting AAOIFI and playing an important role in the formation of IFSB, Bahrain issued a Royal decree to set up another important infrastructure institution, the International Islamic Financial Market (IIFM) in 2002 and host it in Bahrain. The new institution was mandated to develop standardised Shari’a-compliant financial documentation, product confirmations and guidelines for the industry.

Other founding members included the IsDB, Autoriti Monetari Brunei Darussalam, Bank Indonesia, Bank Negara Malaysia (via Labuan Financial Services Authority), the Central Bank of Bahrain and the Central Bank of Sudan.

Since its establishment, the IIFM has been playing an instrumental role, to date, it has issued 12 standards, some of them in collaboration with the Bankers Association for Finance and Trade (BAFT) and the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA). The issued standards are in the areas of hedging, liquidity management & trade finance, which has assisted the industry in being more efficient (by saving time and cost) and enhancing risk management.

Other important organisations hosted in Bahrain with the support from IsDB include:

the General Council for Banks and Financial Institutions (CIBAFI), set up by a Royal decree issued in 2001 with the help of IsDB and a number of other Islamic financial institutions;

the Islamic International Ratings Agency (IIRA), set up in 2005 to provide independent assessments to issuers and issues that conform to the principles of Islamic finance; and the Liquidity Management Centre (LMC), a wholesale bank set up to provide optimal Islamic financing and investment solutions and creating active Islamic inter-bank markets for the development of the industry.

ROLE OF POLICYMAKERS AND THE FUTURE

Imagining a world without standardisation is a difficult task, be it a developed country, an economy, an industry or an organisation. One of the gauges to assess its development and stability is to ascertain clear rules, regulations and procedures laid in a way that are referred to easily.

In the author’s view, a prerequisite for faster growth is comprehensive standardisation, which can be defined as the standardisation of Shari’a interpretation and legal documentation that factors in the requirements of all stakeholders. For investors, it would mean their understanding of Shari’a compliance, the risks associated with their investments as well as the governance mechanism has been taken care of. For regulators, it means their concerns related to the rules and orders are imbedded into the standards development process. For Shari’a scholars, it may mean developing products in line with the market need as well as leaving room for market participants to innovate within the principles allowed. Following a standardised practice will bring the comfort that the processes followed will be the best practices, have global acceptability, and reach over and above being efficient and cost-effective.

AAOIFI has been working on its standards with a 360-degree view covering all areas (Shari’a, accounting, auditing, governance and ethics). To begin with, the Shari’a standards of AAOIFI brings uniformity with respect to Shari’a principles and rules (i.e. what is permissible and what is impermissible in Islamic finance), which sets the foundation for other standards. For example, the governance standards ensure that the implementation of those Shari’a standards are true to the purpose i.e. it helps translate theory into practice. On the other hand, the financial accounting standards, bring uniformity with respect to the reporting of the implementation of those Shari’a standards while the auditing standards assess the quality of the reporting. Overall, the ethics standards exist to help Islamic finance professionals and institutions to uphold the highest standards of excellence in conduct in their work activities. Additionally, the IFSB standards can be adapted to follow the prudential regulations and the IIFM documents can be used to provide standardised documentation for the industry. All in all, the three institutions complement each other in providing the best services to the stakeholders.

The three organisations mentioned above have played an instrumental role in the development of robust standards that are guiding the Islamic finance industry in its growth globally. AAOIFI has played a leading role in the development of standards in its respective areas, the IFSB has played a key role in developing prudential regulations for Islamic banks, takaful and capital market while the IIFM has developed standardised documents that makes the issuance of instruments efficient.

With the development of the Islamic finance industry, the concept of standardisation of best practices is receiving more and more acceptability across the global financial industry. This is evident from the fact that multilateral institutions like the IMF, the World Bank, and the United Nations have been closely monitoring the progress and remain engaged in the work of standards-setting organisations. One evidence of this is the recent endorsement of the use of Core Principles for Islamic Finance Regulation (CPIFR) developed by the IFSB. CPIFR aims to complement the international architecture for financial stability while providing incentives for improving the prudential framework for the Islamic banking industry across jurisdictions. The CPIFR with its methodology will be applied in the financial sector assessments undertaken in fully Islamic banking systems, and as a supplement to the Basel Core Principles for Effective Banking Supervision (BCP), in dual banking systems where Islamic banking is systemically significant1. Additionally, the regulatory bodies have also been more open to adopting standards issued by AAOIFI and IIFM. For example, all AAOIFI standards are fully adopted in Bahrain by the Central Bank of Bahrain as such all banks and financial institutions have to follow the standards issued by AAOIFI while lately, the UAE Central Bank has also enforced the AAOIFI Shari’a standards in the country.

As the industry continues to grow and receives global acceptance, it is important for jurisdictions and countries around the world to follow a defined set of standards that are acceptable, respected, recognised and transferable globally. These standards at present are best described as voluntary and the enforcement of these standards is beyond the scope of the standards-setting bodies and falls within the remit of regulatory bodies. While the development of standards is an important piece of work, the adoption of these standards is far more important. Regulatory bodies in various jurisdictions have the enforcement mandate and are ideally placed to play an important role in the adoption of these standards and best practices. In the author’s view, the real solution is the global adoption of standards issued by AAOIFI, IFSB and IIFM, which addresses the issues mentioned above. This is to ensure that the reputational risk and inefficiency are avoided and the right talent, uniformity and a global appeal is further developed.

This article is written by Dr Rizwan Malik in his personal capacity and the views expressed in this article are authors’ own and do not represent the views of the organisation he works for – Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions.

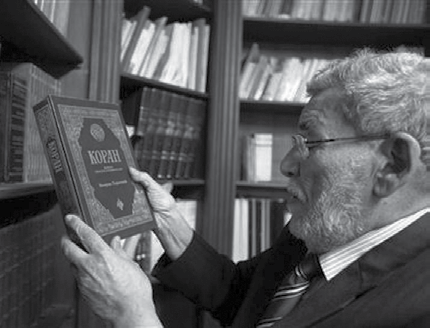

Dr Hussein Hamid Hassan (1932-2020), a jurist, educationalist, Shari’a scholar and advocate of Islamic banking and finance, was a man of multiple talents and exceptional ability. He was at his best when it came to manoeuvring change and influencing thought process. Whether it was leading Benazir Bhutto (late prime minister of Pakistan) to sign off on the large piece of land on which the current campus of International Islamic University Islamabad stands or the likes of Sheikh Mohamed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum (the ruler of Dubai) to garner more of his commitment to Islamic banking and finance, Dr Hassan was a great charmer. Above all, he was a master of the highest calibre in identifying the finest juristic delicacies in intellectual discourse and scholarly discussions and research.

An Egyptian by birth and nationality, his association with Pakistan and love for the country, nevertheless, remained a part and parcel of his personality throughout his life. In 1980, when the International Islamic University Islamabad (IIUI) was set up, he was given the task of developing the university into a global academic institution producing graduates to meet the contemporary challenges in light of, and consistent with, Shari’a. The university has since its inception produced some of the finest brains in Islamic jurisprudence and experts in Islamic economics and finance.

After spending 14 years in Islamabad, he moved to Dubai Islamic Bank in its headquarters, gave new directions to the bank and helped built it on strong juristic foundations, something the bank clearly lacked before that.

Thousands of students of IIUI benefited from his Friday sermons (khutbaat) that he used to deliver as the President of the University. These khutbaat were delivered in Arabic (and summarised in Urdu) and were addressed more towards the university teachers and students than the general public.

The writer is one of the thousands of disciples and students of Sheikh Hussein Hamid Hassan. He had a great way of teaching. The author spent late nights working with him, travelled with him, performed umra with him and worked with him on numerous products and structures. I remember going for umra with him once, from Jeddah to Makkah, probably in 2006. He continued to explain juristic issues during our journey and even during the tawwaf and sa’ii between Saffa and Marwa. He said on the occasion that teaching and seeking knowledge of deen was the best dzikr while performing umra.

Dr Hussein Hamid Hassan was second to none at creating a consensus of opinions during meetings of Shari’a advisory committees. “There is nothing impossible in Islamic jurisprudence (beyond explicitly impermissible things and actions),” he frequently used to say. “If Islam shuts one door, it opens a hundred more.” It may lead someone to erroneously infer that he was a liberal jurist. In fact, he remained a staunch advocate of upholding authenticity in Shari’a structuring. His stance against organised tawarruq and commodity murabaha must continue to remind us of his conservative juristic approach.

Dr Hassan’s juristic approach may seem complex to many who worked with him. He would go into the most delicate details of the transaction before settling on a simple solution. By way of example, when he worked on a prize-linked financial product, he emphasised that it should be developed as a Mudaraba-based investment product, with prizes attached to it. He instructed that it shouldn’t be developed as a prize-giving product that also allowed saving and investing in a Shari’a-compliant way. Although the end result of the two proposals would have been the same, he insisted to do it the way he instructed because it would keep the developments in Islamic banking and finance within the mainstream domain of the Islamic juristic thought. Similarly, when he helped Deutsche Bank to develop a series of Islamic structured products and Islamic financial derivatives, he emphasised on his preference for the nomenclature of Islamic hedging instruments.

Undoubtedly, Dr Hassan had one of the finest juristic minds amongst his peers. Despite having been considered as the top Shari’a mind by his students and disciples, he always gave due consideration and respect to his contemporaries. The writer once asked him to share his view on the ‘number one jurist in the present times.’ He wouldn’t give just one name. He named Sheikh Siddique Al-Dareer before anyone else. When he mentioned of Sheikh Taqi Usmani, he said that he was undoubtedly the lead jurist amongst the contemporary Hanafi jurists. In his response, he also mentioned Syed Abul A’ala Maududi as a great jurist. On the writer’s insistence that Syed Maududi never claimed to be a jurist, Dr Hassan said that he was a jurist of his own kind, who specialised in the Fiqh of Islamic politics and the renaissance of Islam.

Sheikh Hussein, as he was commonly referred amongst his students, had great sense of humour, which he would use to please people rather than putting them down. Dr Adnan Aziz and the author worked very closely with him during their days at Deutsche Bank. The author served as Secretary of the Shari’a Board and Dr Aziz was responsible for liaising with the members. At the start of a meeting in Doha, Sheikh acknowledged the hard work of the two by referring to them as ‘Sahibaan,’ which was obviously pleasing to both of them, given the historical significance of the reference to Imam Abu Yousuf and Imam Muhammad, the two companions and disciples of Imam Abu Hanifa.

Similarly, once he was having dinner in the dining hall of one of the colleges at the University of Oxford. I think it was Dr Aziz who pointed to a huge painting of someone hanging on the wall on his back and asked, “Sheikh, is it allowed to paint human figures or get someone painted?” Dr Hassan smiled and instantly said, “Yes, if the painting is of that size.”

Born in Egypt as Hussein Hamid Al Syed Hassan on July 25, 1932, he passed away on August 19, 2020, in Cairo. He was a law graduate of Al-Azhar University from where he also received his PhD (1965). He also studied comparative laws and economics at the International Institute of Comparative Law (New York) and Cairo University. In 2013, Durham University conferred on him an honorary doctorate in civil law.

During a career spanning over 60 years, he was involved in leadership positions in numerous projects of impact and influence. He authored 20 books, over 400 scholarly articles, and supervised the translation of the Holy Quran and about 200 books into the Russian language. His Shari’a advisory engagements abounded most notably the chair of the Shari’a Advisory Committee of Islamic Development Bank.

Dr Hassan is survived by seven sons, four daughters and thousands of students and disciples spread all over the world.

The writer is Professor Humayon Dar, Director-General, Cambridge Institute of Islamic Finance.