Introduction

The flow of capital around the globe is a major determinant of economic activity within countries and sectors. As the barriers to the flow of money have become increasingly feeble, capital tends to move wherever it perceives it will find the most attractive risk-adjusted returns. As capital flows to a particular place, it brings prosperity to those who can take advantage of the opportunities which emerge from the increased pace of economic activity. Conversely, as capital leaves a system, economic recessions, poverty and social unrest ensue.

There isn’t a central planner deciding where capital should flow around the globe. Rather it is the interaction of billions of individuals which determines the direction of liquidity. And whilst the action of an individual might not matter much (unless that individual is a powerful central banker!), the combination of multiple actions may indeed make a significant impact on the direction of the flow of liquidity.

In addition, the way capital flows also makes a difference. It is common knowledge that excessive use of interest-bearing debt to finance expansion may lead to speculative bubbles, and subsequently may accelerate the crisis through widespread bankruptcies. Equity-based modes of finance are thus to be preferred, although not immune from the ever-present threat of irrational exuberance.

Shari’a-compliant finance offers solutions for those individuals who have a deep belief that the society would benefit from the flourishing of business sectors which are essentially “Halal”, and that the way capital flows into those activities is equally important. It is the role of professionals engaged in delivering Shari’a-compliant investment products not to frustrate the aspirations of Shari’a-compliant investors, but to deliver outstanding solutions to meet their objectives.

In aiming to invest in a Shari’a-compliant way, an investing entity will have two considerations: the performance of the project and the return it produces. These factors are interrelated. Companies are constantly looking to ensure they can sustain their activities, and therefore a circular relationship ensues. Consistent investment of the right quantum leads to companies able to sustain their operations which will hopefully meet or generate demand. If demand is good, investing entities will be more inclined to invest.

In respect to the two considerations, investing entities will concentrate on one or the other, even though the two are related. When it comes to asset management, the investing entity is concerned about return through dividends or capital gains. On the other hand, when it comes to investing into large scale projects, the investing entity will be interested in performance. To explain, if investing entities disburse funds into infrastructural projects, for instance oil and gas exploration, they will expect suitable returns in the near future resulting from successful operations of the project.

Thus the investing entities in the first scenario will have indirect involvement in the production of real goods and services while investing entities in the second scenario will have direct involvement. In this chapter we explore the Shari’a issues that arise through indirect and direct investment into the production of real goods and services, and their relationship with the investor. The chapter will be divided into two sections and looks at the structuring issues involved. The first section looks at indirect investment, and more specifically investment into different asset classes. The second section looks at direct investment, and more specifically project finance.

Part 1: Structuring Islamic Investments

Shari’a-compliant investors have access to a wide spectrum of investment opportunities both domestic and international. This has been made possible by a wave of product developments which over the last 20 years have progressively broken new ground. In the process, both praise and criticism has been raised against the present status of the Islamic asset management industry on ac- count of some of the “legal structures” which have been devised to achieve the objective of investing in a particular asset class.

As the Islamic finance industry moves forward to deliver outstanding asset management services to those investors who have decided to manage their portfolio in a Shari’a-compliant way, it is important to take a critical look at the structures of the investment products currently on offer, and to recalibrate the efforts towards the ultimate aim pursued by both investors and product providers.

In what follows we will first provide a brief overview of the context in which Shari’a-compliant asset managers operate, and then delve into the building blocks of a number of solutions which have been developed to invest in various asset classes, to identify possible areas of improvement.

The Nature of Money

The first step towards structuring Islamic investments: understanding the nature of money. A correct understanding of the nature of modern-day money is a concept which eludes many, but is essential in the job of delivering Shari’a compliant investments. We are so accustomed to use those pieces of paper or plastic cards in our wallets, or the numbers displayed on our online bank accounts, that we rarely remember that we are living in a relatively recent giant experiment called “fractional reserve banking” based on the universal use of “fiat money”.

This modern system has replaced gold and silver, the assets which for millennia performed the role of money, with a complex web of “promises” recorded on physical or electronic platforms. Bank deposits (paper money being just a bearer cheque issued by the central bank) are the first block of the modern monetary system; and what we call “money” in reality is something completely different from gold and silver.

Money is a sort of “voucher” or “coupon” which is commonly accepted in the market in exchange for “real” goods or services at any time and in any place. Money is essentially a bank deposit, and bank deposits are a special kind of “loan”. The depositor has lent an abstract object called “purchasing power” which it obtained from some other party and was ultimately created within the banking system by an act of recording a loan against a deposit, i.e. a mere book entry. Shari’a scholars (not without exceptions) have accepted “fiat money” as a valid Shari’a-compliant medium of exchange, and have extended to it the rules for dealing in gold and silver.

At the opposite end of the “liquid” spectrum, we find a host of assets which qualify as quasi-money: listed equities, listed commodities, listed real estate, listed private equity, etc. For example, it is common knowledge among finance practitioners, that a listed company can literally print its own currency, by issuing shares on a stock exchange. If the shares are valued at a substantial premium, they could be used to acquire another company, without compromising the control of the acquiring company.

In respect to these liquid assets qualifying as “quasi- money”, Shari’a scholars have decided not to extend the rules of “fiat money”, leaving a door open for Islamic banks to continue their activities of financial intermediation using debt-based finance modes. Islamic banks, using quasi-money have been able to develop an alternative set of products to raise finance from their depositors and redeploy it within the economy, without compromising their liquidity.

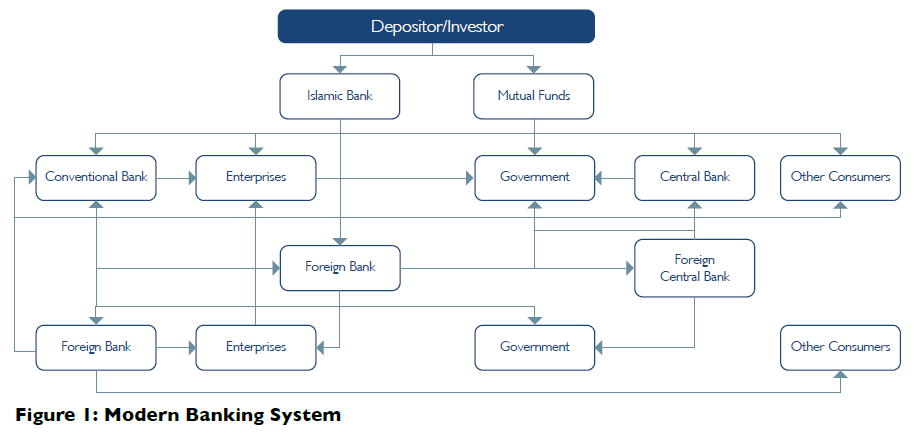

One remarkable feature of the modern commercial banking system is that it is designed in such a way that every unit of currency deposited with a bank is automatically reinvested or lent somewhere around the globe, the very moment that the unit is created (Figure 1).Whether the deposit is structured as an interest-bearing loan or as sales of a liquid asset (commodities or equities) with a deferred payment, the economic result does not change.

In many aspects this is a very positive feature as it has eliminated the widespread phenomenon of hoarding (“burying gold underground”). In this system, even if depositors are risk averse, and banks are risk averse, the central bank can recycle the liquidity in the system by lending either to the government or to the wider economy.

Islamic banks are fully integrated into this system, and perform the important role of redirecting the flow of capital in a way that matches the preferences of Shari’a-compliant investors. Therefore, investors who want to ensure that their portfolios are invested in a Shari’a-compliant manner need to follow the trail of where their money is ultimately invested or used, and can do so starting by entrusting their money to Islamic financial institutions (IFIs) and asset managers in order that it is channeled as far as possible to the Halal economy.

Investing in Liquid Assets

Islamic banks have developed business models broadly similar to conventional banks, raising finance through short term deposits and lending the money prevalently through debt-based modes of finance.

The abundance of liquidity injected in the system by international central banks in the aftermath of the recent financial crisis has greatly lowered the cost of finance for investment grade borrowers and impacted the profit rates that Islamic banks can pay to their depositors. Shari’a-compliant investors cannot just wait for international liquidity markets to normalize and Islamic profit rates to grow back to historical averages. This would be a very dangerous investment strategy as the purchasing power of a bank deposit is threatened by the progressive inflation of productive assets (caused by leveraged investors who can take advantage of low cost of borrowing), and potential devaluation of their home currency relative to other international currencies.

Investing in listed equities, sukuks, commodities and foreign currencies is a valid alternative to bank deposits provided that appropriate risk management tools are implemented. A number of Shari’a-compliant “capital protection” strategies or products are available in the market to help investors diversify away from bank deposits.

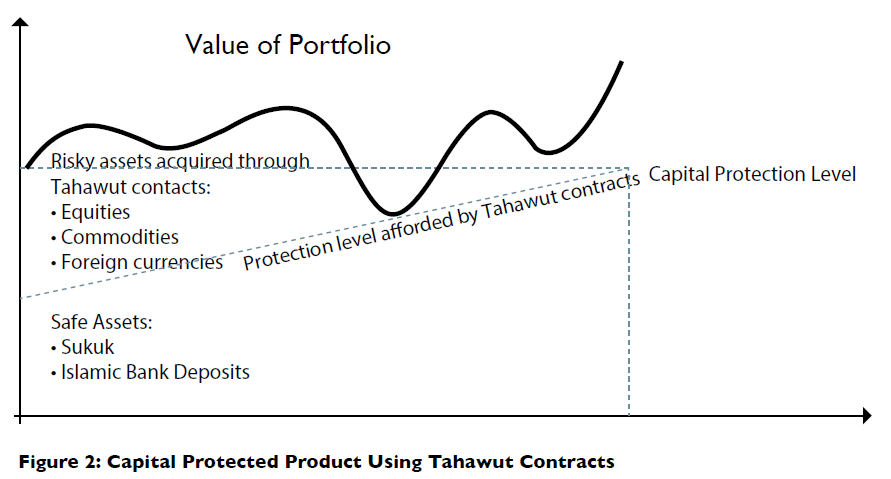

The simplest form of capital protection strategies is one which systematically implements “stop losses” and “volatility control” techniques. This strategy adds to the investment mandate of the fund manager an additional set of instructions to reduce exposure to risky assets when either market volatility spikes, or when prices start trending down. A more complex form of capital-protected products are those that involve the use of so called “Tahawut” contracts (literally “to protect oneself” or to “hedge”), to place a contractually agreed floor to the value of the portfolio even in the presence of severe market volatility. Figure 2 provides an example of how the value of a portfolio of liquid Shari’a compliant assets could be protected using a Tahawut contract.

A large portion of the portfolio is invested in sukuks and deposits with Islamic banks. This portion of the portfolio is considered “safe” and generates a predictable rate of return over time until its value is equal to the initial value of the portfolio. This is what is meant by “capital protection”. Of course, in case of default of the sukuk or of the Islamic bank, the capital protection feature will be lost; but this shifts the analysis to credit as opposed as price risk.

The remainder of the portfolio is invested in riskier assets like listed equities, commodities and foreign currencies, which typically experience wild and random price fluctuations in the short term, but can generate attractive long term returns once the fund manager identifies a correct trend. In order to mitigate the risk of investing in these assets, the portfolio manager will utilize option- like contracts documented under a tahawut framework. Without entering into greater details, these contracts avoid losses on the risky part of the portfolio, which impair the ability of the portfolio manager to achieve capital protection at maturity, through a buy and hold strategy of the safe investments.

If for example the portfolio manager can achieve an average rate of return of 4% p.a. on the safe part of the portfolio, over a 5 years investment horizon the capital will be protected even if the amount invested in risky assets is entirely lost. The best case would be a scenario where the manager is able to generate a return of 20% p.a. on the risky side of the portfolio. In this case, the total return of the portfolio would be a respectable 8% p.a.

This return compares well with a buy-and-hold strategy of a portfolio of global equity, which historically would have generated a similar return but with far higher volatility and drawdowns. Shari’a compliant capital protected products have at times attracted criticism, some of which was warranted, some not. For example, in the past a number of Shari’a-compliant capital-protected products linked to conventional hedge funds were offered to the general public, causing considerable bad press. However, the criticism that “capital protection” cannot be associated with Shari’a compliant products in absolute terms may be less grounded, as there is no good reason to ask Shari’a-compliant investors to operate under a different risk-return profile than conventional investors.

In particular, Figure 2 above shows that the suggested investment strategy allocates the vast majority of the assets to instruments issued by companies operating in the Halal economy, and therefore satisfies the broader macro-economic goal to encourage the flow of liquidity in accordance with the founding principles of Islamic finance.

Real Estate and Infrastructure

Investing in real estate and infrastructure poses a different set of issues for Islamic investors. Physical properties are a natural substitute for fixed income instruments as there is widespread agreement among Shari’a scholars that the nature of rent of a durable asset is different from the interest accruing on a loan of money or of a consumable asset.

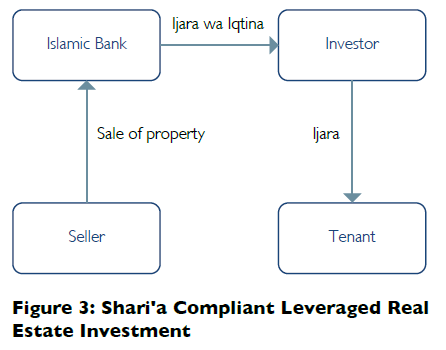

In addition to income, the ongoing process of urbanization in many Muslim countries offers an opportunity to generate substantial capital gains by getting involved at the construction stage of the infrastructure of a modern economy. The large cost associated in purchasing or developing physical assets, together with the need to diversify one’s portfolio and obtain attractive rate of returns, often means that a certain degree of external financing must be employed in a real estate or infrastructure investment. The use of leverage adds an undesirable element of uncertainty at a micro level, and could have spillover effects at a macro level if the individual actions of investors lead to a property bubble. The use of Shari’a-compliant modes of financing (ijara wa iqtina and istisna), can alleviate to a certain extent the above concerns (but not eliminate them completely). Figure 3 shows how Shari’a-compliant leverage can be added to a real estate or infrastructure investment.

The Islamic bank, or a financier, will acquire the physical property of the asset and will grant its use to the investor under an ijara wa iqtina. The investor will further grant the use of the property to a third party under a normal ijara. Typically, the investor will have the right to purchase the property from the financier at the end of the lease, and resell it in the market to realize a capital gain.

Investors will typically pay close attention to the end use of the property. Certain commercial tenants (e.g. conventional banks, gambling operators, producers or sellers of intoxicants, etc) will be excluded outright. Other tenants (e.g. logistics) will require analysis on a case-by-case basis to understand exactly what type of activities they engage in.

The use of Shari’a-compliant finance should provide certain key benefits to the investor. For example, if the underlying tenant is in arrears on rental payments, the Islamic financier should not apply penalty interest on over-due rents, avoiding further compounding the problem.

Also, because the Islamic financier is already the owner of the property, there will be less room to add to the ijara wa iqtina agreement covenants linked to loan-to-value ratio which could force the investor to accelerate the repayment of the financing if the value of the property falls below a certain level.

In general, one would also expect more leniency from the management of an Islamic bank (provided the Islamic bank is true to its funding principles) if the investment does not go exactly as planned, and there is a need to renegotiate the agreement.

Private Equity

The meaning attached to private equity in this chapter is the service offered by fund managers who invest in privately owned companies on behalf of third-party investors, and implement a number of policies to enhance the value of the company and subsequently resell the company at a higher value. It does not include investing in companies for the purpose of expanding the activities of an industrial conglomerate, with the objective of deriving long term dividends.

Private equity investments, as defined above, have been an area where Shari’a compliant investors have not been particularly active over the last few years, despite offering some very attractive returns. Domestic private equity investments in OIC member countries have been relatively easy to execute, but difficult to exit due to various reasons, primarily the lack of developed local listed equity markets.

International private equity investments in non-OIC member countries have encountered structural challenges of implementing Shari’a compliant investment guidelines in the context of a relatively illiquid asset class. As the flow of private equity deals grew in size and complexity, international fund managers have shown reticence to accommodate Shari’a compliant investors alongside less demanding conventional investors.

Usually, a Shari’a compliant investor will shy away from leveraged buyouts, since it would be nearly impossible in current market conditions to raise Shari’a compliant financings in competition with conventional investors who can easily structure conventional facilities.

Shari’a compliant private equity activities are therefore limited to the more traditional areas of management buyouts, turnaround and growth expansion. Venture capital (i.e. investing in Greenfield projects without recurring revenues) has not attracted a lot of interest due to the inherent risk of the activity, and the lack of proximity to the industrial hubs where such investments are made.

A little investigated area where Shari’a compliant investors could find opportunities is that of financially distressed companies with an underlying healthy business. Interestingly, some Shari’a boards have allowed investments in distressed securities (that is bonds) of insolvent companies under certain conditions and without the need for complex legal structuring, provided the investor undertakes to repair the balance sheet of the rescued company in a Shari’a compliant manner.

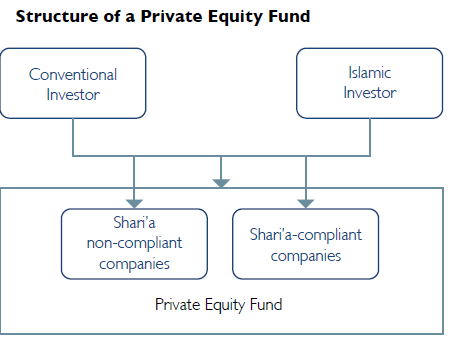

A Shari’a compliant investor has basically two choices: either to be a minority investor, or a majority one. As a minority partner, the Shari’a compliant investor is allowed to participate in companies after applying certain sectorial and financial filters, an example of which is given on the left panel of Figure 4. In addition, the investor will need to purify the dividends received from the company, by giving to charity a percentage of the dividend income calculated on the basis of the portion of Shari’a non-compliant earnings of the company.

Challenges arise if the company breaches those limits after the investment is made. Typically, the Shari’a compliant investor will wait a certain period of time to see whether the breach can be remedied, and may also remark his dissent to the other shareholders. But being in a minority position, he cannot impose his will and at the expiry of the grace period will have to exit the investment, something which will make him a forced seller of an illiquid asset.

The solution to this serious problem is in finding a fund manager endowed with substantial internal resources and willing to bail out the investor in case of a breach which cannot be remedied. The Shari’a compliant investor and the fund manager will co-invest in a portfolio of companies, agreeing on a set of Shari’a compliant screens. If one or more companies in the portfolio be- come Shari’a non-compliant, the fund manager will ac- quire them from the investor at fair market value and transfer them to a different pool within the portfolio un- til these companies are either exited or become Shari’a compliant again (see right panel of Figure 4).

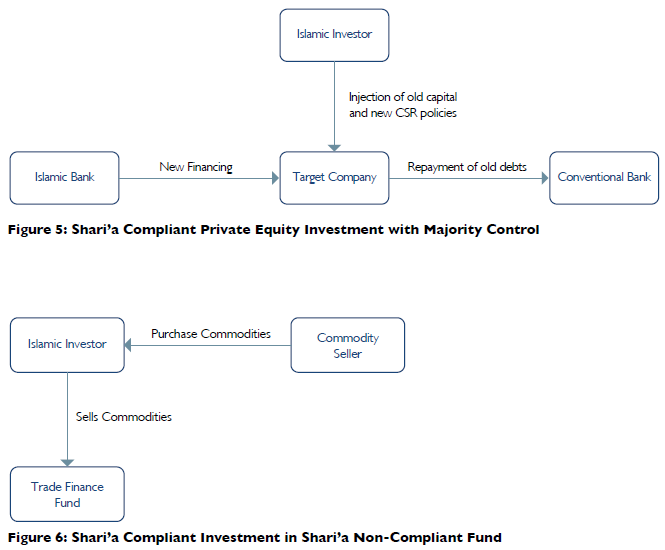

Figure 5 outlines the modus operandi of Shari’a compliant private equity investments when a majority or a controlling stake is sought. The investor will contribute capital to a fund alongside the fund manager to inject equity in the company.

Within a specified grace period agreed with the Shari’a board, the fund manager will endeavor to raise finance from Shari’a compliant lenders to replace the old conventional lenders. At the same time, all interest rate and currency derivatives will be restructured.

In addition to the financial turnaround of the company, the fund manager will implement a set of Corporate Social Responsibilities (CSR) policies drafted according to Islamic principles, to regulate the behaviour of the company towards all its stakeholders, including employees, customers, suppliers and host communities.

Finally, under the supervision of the Shari’a board, a review of the business lines will also take place to eliminate non-Halal products, and terminate client relationships where the company’s products are obviously used for non-Halal purposes (e.g., most Shari’a boards will deem it impermissible to supply grapes to a wine-maker).

The exit strategy for such a private equity investment might pose some complexities. If the target company can be listed on the exchange of an OIC member country, there may be sufficient demand from local Shari’a compliant investors to enable the private equity investor to exist his stake. Otherwise, most probably the owner will need to identify another Shari’a compliant private buyer, as it is unlikely that such a company could be of interest to investors residing in non-OIC member countries.

Other Alternative Assets

There are investments in assets which are inherently Shari’a compliant, apart from some elements which cannot be restructured, making the whole investment non-eligible for a Shari’a compliant investor. The two particular asset classes falling in this category are trade finance funds and leasing funds.

The preferred route for investing in these asset classes would be to agree with the fund manager a bespoke mandate where all contractual obligations of the portfolio are drafted according to Shari’a compliance principles. For example, there should not be penalty interest clauses for late payments, and the manager should not deal in non-Halal goods, or lease assets to companies engaged in non-Halal activities.

When it is not possible to structure such a bespoke Shari’a compliant product, investors may ask permission from the Shari’a board to implement the structure out- lined in Figure 6, after having satisfied themselves that the majority of the income of the underlying fund (e.g. at least 95%), is derived from Shari’a compliant activities.

Figure 6 describes an investment in a trade finance fund, but a similar structure can be designed for a leasing fund. The investor and the fund manager contribute capital in a portfolio. The money of the portfolio will be used by the fund manager to acquire commodities from a supplier and sell them to the trade finance fund on the basis of a spot delivery and deferred payment. The difference between the purchase price and the resale price will represent the profit for the portfolio and will be determined on the basis of the estimated going return of the fund. Divergence between the estimated return and the actual return of the fund can be adjusted with additional commodity murabaha trades.

The above structure is open to criticism, because it bypasses the need to implement a correct set of Shari’a-compliant contractual agreements with the end counterparties of the fund. In addition, the investor will need to provide a valid explanation to the Shari’a board for transferring money which would otherwise be deposited in an Islamic bank, conventional trade finance or a leasing fund.

Shari’a scholars have extended to “fiat money” the rules which apply to gold and silver. More freedom of action has been left in respect to other liquid assets qualifying as “quasi-money” setting the stage for Islamic banks and asset managers to develop a Shari’a compliant financial system which channels liquidity to the Halal economy. Practitioners engaged in structuring Islamic investment products, need to find the right balance between the macroeconomic role they play in the Halal economy, and the need to deliver quality products and services that address the immediate needs of their clients. The leniency of the scholars in approving a wide range of investment products should not be interpreted as a carte-blanche to structure any sort of investment which nominally complies with the rules but defeats their spirit. It remains the responsibility of those developing financial products to ensure that “purchasing” power flows to the Halal economy. Shari’a scholars have allowed Islamic banks to participate in an international financial system which continually expands the monetary base, in essence creating purchasing power for the recipients of this newly minted money, without relation to goods, services and other physical assets available in the market. Prudent monetary policy would typically fine tune the amount of money to the level of economic activity, and Shari’a scholars are very concerned with any phenomenon which might create disruptions to the welfare of the society, especially so if created by the very financial institutions they have assisted to create. It should not be surprising if occasionally Islamic scholars issue criticism against products which have gone beyond the scope of the Halal economy, be they retail loans based on tawar-ruq, sukuks not backed by real assets or capital protect- ed products linked to conventional hedge funds. Banking regulators too are taking a very close look at the way all financial products are structured, and to the wider effect they produce on the society, often calling to account those bankers and fund managers who bend the rules and cause financial losses to their clients. Practitioners in the Islamic financial sectors should pay attention to both regulators and Shari’a scholars.

Part 2: Islamic Project Finance

Islamic project finance is growing rapidly as the typical infrastructure and development objectives of project finance make it a suitable candidate for Islamic finance. Historically, Islamic financing structures were not been widely utilized in large-scale project financings due to the requirement for long tenors. In the recent past, a growing portion of the long-term project finance raised in the GCC region has included Shari’a-compliant facilities.

There is now little concern from a Shari’a perspective with funding a project using both Islamic and conventional financing. The interface between Islamic and conventional financiers on issues such as pro rata utilizations and payments, security sharing, sharing of sponsor support and post-enforcement cash flows are now largely settled, but continue to be refined. While no two transactions are the same, certain standardized documents and market practices are emerging as the field continues to develop. Still we are a far way away from settled documentation, and changes are common and often required to accommodate comments from the Shari’a boards on each deal.

The istisna-ijara structure has emerged as the product of choice for Islamic project financings, followed by the wakala-ijara structure. These products are well-suited for project finance as they offer the certainty of regular payments throughout the life of the financing with the flexibility of tailoring payments and tenor in a manner that allows Islamic financiers to match the cash flows of the project and achieve profit margins comparable to that of conventional financiers. Project sukuk is also set to play an important role in the Islamic project finance market going forward given strong demand from investors, lower cost of issuance compared to conventional bonds, attractive pricing, increased standardization and political commitment to develop the region’s capital markets. The murabaha/tawarruq structures will continue to play an important supporting role for providing short-term financing for working capital facilities and equity bridge financing given their flexibility and low risk. What remains to be seen is the utilization of Islamic hedging (tahawut) and Islamic insurance (takaful) as part of project financing transactions.

This recent growth has been assisted in large part by the commitment of project sponsors (and their host governments) to promote the Islamic finance industry. This commitment stems from the broader consumer demand for Shari’a compliant financial services and products in many Muslim countries. Project sponsors, who are looking to the IPO markets as a possible exit route, have come to recognize that the public’s appetite for the shares in such companies is driven, at least in part, by compliance with Shari’a.

Another reason why project sponsors are keen advocates of Islamic project financing is that, given the capital-intensive nature of the recent mega-projects undertaken in the GCC region, project sponsors are eager to draw on all available funding sources. This has been coupled with increased liquidity in IFIs and better risk management techniques. This has allowed the IFIs to participate in project financings with longer tenors and develop a full range of Shari’a compliant products capable of utilising a project’s underlying tangible and intangible assets. We look at some of these products below.

Istisna-Ijara and Wakala- Ijara

The istisna-ijara combination has emerged as the most commonly used Islamic project finance structure for large and long-term financings. The combination of the istisna (a sale contract that can be applied for the pro-curement (or development) of an asset during the project’s construction phase) and ijara mawsufa fi al dimmah (a forward lease under the terms of which that asset, when completed, is leased to the Project Company) has become an acceptable alternative to the traditional conventional project debt facility. The current form of the istisna-ijara structure has been used since around 2000. It is now a settled structure and a measure of standardization has been achieved in its documentation.

In order to satisfy the requirements of Shari’a boards of certain Saudi Arabian banks for whom the istisna- ijara structure may not be acceptable, the structure is often used alongside a wakala-ijara structure, which is preferred by the Shari’a boards of those Saudi Arabian banks. This was the case in the Riyadh PP11 Project and the Rabigh IPP Power Plant (Saudi Arabia 2010 and 2009) as well as the SATORP and Sadara Projects (Saudi Arabia 2010 and 2103). The wakala-ijara structure is preferred by certain Saudi Shari’a boards because in this structure, the Project Company does not act as the pro- curer of the project assets which it then leases back, but instead acts as the wakil (agent) of the Islamic financiers in arranging the construction of the project assets by a third party EPC contractor.

The istisna-ijara and wakala-ijara structures are well-suited for project finance as they provide for phased payments of the construction price (which may be linked to construction milestones) with the flexibility of tailoring payments and tenor in a manner that allows Islamic financiers to match the capital expenditure and cash flows of the project and achieve profit margins comparable to that of conventional financiers.

Key Differences between Istisna-Ijara and Wakala-Ijara

For ease of reference, we will call the istisna-ijara structure the “Procurement Facility” and the wakala-ijara structure the “Wakala Facility”.

- The Asset

Both the Procurement Facility and Wakala Facility finance the construction of an asset. The value of the asset to be procured or constructed will reflect the size of the relevant facility. Financing integrated parts of a large project is acceptable but a single asset which is clearly identifiable is often preferred. Assets have included turbines, liquefaction and refrigeration units, storage tanks and offshore oil and gas platforms. Depending on the preference of the participants and their Shari’a boards, the assets allocated in the Procurement Facility may be expressed as a percentage of the overall project assets, or a list of assets (usually expressed as a short-form list of bullet points). In the Wakala Facility, much more detail is provided and the list of assets is usually accompanied by several pages of technical specifications.

- Initial Wakala Agreement

In many large projects, the EPC contracts are entered into before the financing arrangements are put in place. To allow the customer to enter into the EPC contracts prior to the execution of the Wakala Facility documents (specifically the Wakala Agreement), an Initial Wakala Agreement is entered into between the customer (as agent) and an Islamic financier on behalf of the future Wakala Facility participants. This Islamic financier may be the customer’s financial advisor or a bank that is likely to be involved in the future Wakala Facility. Under the Initial Wakala Agreement, the customer is appointed as the Islamic financier’s undisclosed agent for entry into the EPC contracts. The Initial Wakala Agreement will automatically terminate upon the signing of the Wakala Agreement. This Initial Wakala Agreement is required to maintain the Shari’a compliance of the future Wakala Facility, so that the customer enters the EPC contracts on behalf of the Wakala Facility participants (who will be the eventual owners of the assets). There is no such requirement under the Procurement Facility as the customer will act as the procurer for the Procurement Facility participants.

- Governing Law

In the major deals undertaken in the GCC, the Procurement Facility participants tend to sign documents governed by English law (which includes the Procurement Facility documents). This is not acceptable to the Shari’a boards of the Wakala Facility participants who require that the Wakala Facility be governed by Saudi law in accordance with Shari’a principles. Therefore, the Wakala Facility Participants do not sign any of the common finance documents such as the Common Terms Agreement (CTA) and Intercreditor Agreement (ICA). On the other hand, the Procurement Facility participants sign the CTA and ICA. This means the Procurement Facility functions similarly to a conventional facility where certain key provisions are incorporated from the CTA. Also significant from a documentation perspective is that the definitions and construction provisions in the Procurement Facility are incorporated by reference to the CTA and do not need to be set out in each of the Wakala Facility documents (to the extent relevant).

- Wakala Undertaking Agreement

If the Wakala Facility participants do not want to sign the CTA or ICA with conventional financiers, they may be willing to enter into a Wakala Undertaking Agreement whereby they take benefit of the security package provided under the main financing and undertake to only exercise their rights under the Wakala Facility (where they own certain assets) in accordance with the ICA. The Wakala Undertaking Agreement is usually governed by English law to provide adequate confidence to the conventional financiers that the undertaking will be enforceable. As the Procurement Facility participants are usually willing to sign the ICA, no separate undertaking agreement is usually required for that facility. The result is that both the Wakala Facility and Procurement Facility participants share the proceeds of any enforcement with other financiers participating in a project.

| Project | Year | Country | |

| EMAL Aluminium Project Phase II | 2013 | UAE | |

| Sadara Refinery and Petrochemical Project | 2013 | Saudi Arabia | |

| Barzan Gas Project | 2011 | Qatar | |

| SATORP Refinery and Petrochemical Project | 2010 | Saudi Arabia |

Table 1: Recent Project Financing Using Istisna-Ijara Structure

- Financial Terms

In the Procurement Facility, a separate suite of documents is often used to document financing offered in different currencies (e.g. US Dollar and Saudi Riyal). In the Wakala Facility, the Dollar and Saudi Riyal tend to be documented in the same suite of documents. Another key difference is that in the Procurement Facility the stage payments are made at the request of the customer (as procurer) and function similarly to a utilization request under the conventional facilities. The advance rental payments and lease rental payments are paid by the customer in accordance with a formula that incorporates a benchmark (such as LIBOR) plus a margin. The formula incorporates amounts that are equivalent to the commitment fee payable under the conventional facilities. Under the Wakala Facility, the stage payments and lease payments are made in accordance with a fixed schedule set out in the documents determining the exact date and amount to be paid. This is to achieve a higher level of certainty to avoid compromising the Shari’a compliance of the facility due to gharar.

Under the Wakala Facility, the Wakala Facility participants are expected to pay the customer a “wakil fee” and “services fee” for its role under the Wakala Agreement and Service Agency Agreement respectively. These amounts are usually set-off against the first advance rental payment to be made by the customer to the Wakala Facility agent (on behalf of the Wakala Facility participants). The Wakala Facility participants are also paid an administration and management fee that tends to be equivalent to the commitment fee and upfront fee payable to the conventional facility participants. Under the Procurement Facility, a nominal fee (e.g. US$100) is paid to the customer as “procurer” and “service agent” under the Procurement Agreement and Service Agency Agreement respectively.

Project Sukuk

Project sukuk is a recent addition to Islamic project finance instruments, but is set to grow rapidly. Strong demand from regional and domestic investors, lower cost of issuance compared to conventional bonds, attractive pricing, increased standardization and political commitment to develop the region’s capital markets have all contributed to the growth of sukuk in general, and project sukuk in particular.

Although there have only been a small number of project bonds or sukuk issued as part of Greenfield multi-sourced project financings to date, the market sentiment is that this situation will soon change. The project Sukuk issued with regard to the SATORP Refinery and Petrochemical Project (Saudi Arabia 2011) was the first project sukuk issued and was over-subscribed by almost 3.5 times. This was followed by the issuance of the sukuk for the Sadara Petrochemical Project (Saudi Arabia 2013). The Sadara sukuk has a tenor of 16 years and is unique in that it forms part of the project’s initial financing plan, which also includes funding from export credit agencies, Saudi investment funds, and conventional and Islamic banks. The SATORP sukuk had a 14-year tenor, which is typical for project financings, but longer than historical sukuk tenors (which tend to be between five and seven years).

It is now common practice on large-scale financings to pre-structure the documentation to accommodate project bonds or sukuk even though there is no intention for them to be issued as part of the initial financing. In some ways, project sukuk can be advantageous for project companies and sponsors as it may offer better pricing and longer tenor than those currently available in the Islamic commercial bank market. Also, sukukholders are typically afforded less oversight compared with the active management of projects by investment agents acting on behalf of Islamic commercial banks.