The Global Islamic Finance Report (GIFR) is the first report to have documented the size and growth of the global Islamic financial services industry since its inaugural edition in 2009. The GIFR 2010 was the first publication to report that the Islamic financial assets had exceeded

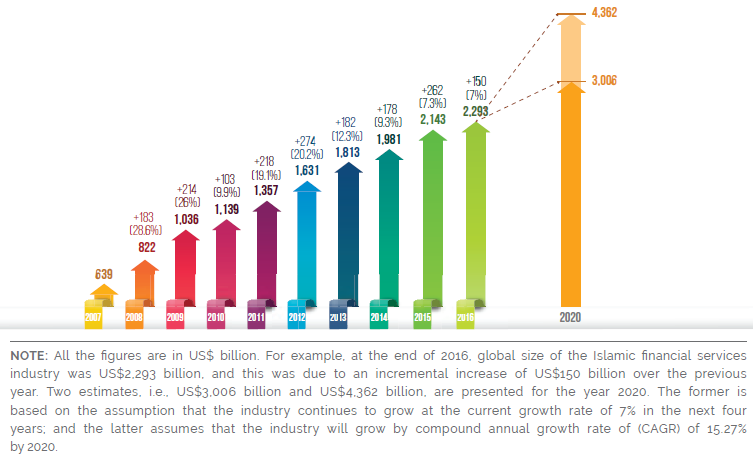

US$1 trillion by the end of 2009. Following the tradition, this introductory chapter reports that the global Islamic financial services industry stood at US$2.293 trillion at the end of December 2016 (see Figure 1), an additional stock of US$150.01 billion over the last reporting year when the industry stood at US$2.143 trillion (at the end of 2015).

The estimated size of the industry is based on the assumption that the potential size of the industry grows by at least 10% annually. This assumption is based on a number of factors:

Global Muslim population continues to grow;

Awareness about Islamic banking and finance (IBF) continues to rise; and

The per capita income and wealth held by Muslims are also rising, in line with the trends in other faith-based groups.

With the third consecutive year of single-digit growth – 7.0% growth in 2016, compared with 7.3% in 2015 and 9.3% in 2014 – the global Islamic financial services industry seems to have reached a point where all the stakeholders must pause to re-think the future strategy for growth and expansion. Our projected growth rate for 2016 was 7.41%, implying that the global Islamic financial services underperformed by a margin of 5.65%. The slowdown in the industry necessitates us to revise downwards the estimates of future size of the industry. The GIFR 2016 forecasted the industry to grow between US$3.151 trillion and US$4.57 trillion. Based on the above assumptions and prevailing economic conditions, the new forecast is given in Figure 1.

The slow-down in growth may be attributed to a number of factors, including:

Political conflicts in a number of Muslim countries, particularly in the Middle East.

This has hampered the growth of IBF in countries such as Iraq, Syria and Libya etc., contrary to the views held by industry experts in the aftermath of the so-called Arab Spring;

Historically low-oil prices, which have affected the countries in the Gulf Corporation Council (GCC) and others where IBF is a major component of the financial markets;

The enthusiasm of Western financial institutions towards IBF is receding. It appears as if the days are gone when Western financial institutions would get lured to IBF, expecting access to a red-hot pot of Islamic money; and

Maturity of IBF in key markets like the GCC (barring Oman) and Malaysia, which is leading to natural slow down.

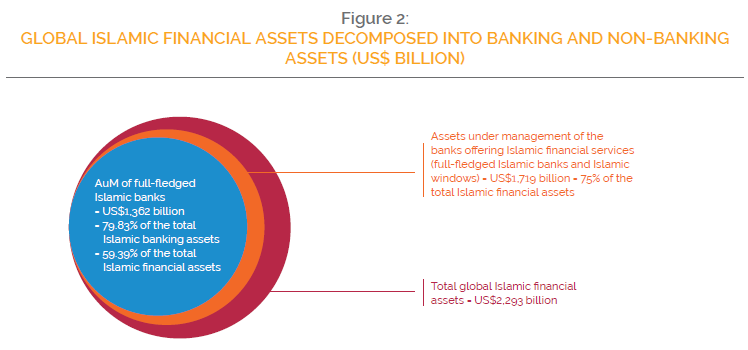

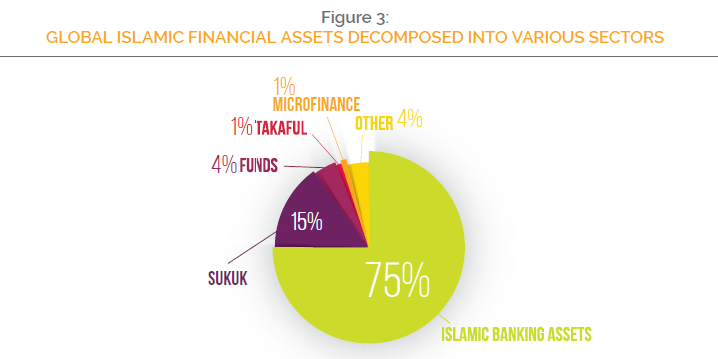

Banks continue to dominate in terms of assets under management (AUM) of Islamic banks and financial institutions (IBFIs), with 75% of the global Islamic financial assets held by Islamic banks and conventional banks in their Islamic window operations. Out of the Islamic banking assets, almost 60% are held by full-fledged Islamic banks (see Figure 2). This clearly indicates that a pure (full-fledged) Islamic banking model is still a preferred choice over a subsidiary or window model. The future of Islamic banking clearly lies in developing a completely segregated Islamic banking model rather than a dual banking model built on hybridisation of Islamic and conventional banking.

The second largest sector in terms of AUM is sukuk, which comprises 15% of the global Islamic financial services industry. Islamic investment funds have yet to see any significant growth and so is the case for takaful and the emerging business of Islamic microfinance (see Figure 3).

Due to the widening gap between the potential size and the actual size of the global Islamic financial services industry, the catch-up period, i.e., the number of years required for the supply side of the IBF to meet all the demand for Islamic financial services, has also increased from 27 years (as reported in GIFR 2016) to 35.2 years (Table 1). On a government level, the countries like Malaysia and Indonesia have set national targets for Islamic banking and finance (IBF). In case of the former, the government aims at achieving 40% market share of Islamic banking by 2020, while the latter has a target of 15% by 2023.

| 2009 | 2010 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | ||

| POTENTIAL SIZE OF THE GLOBAL ISLAMIC FINANCIAL SERVICES INDUSTRY (US$ TRILLION) | 4 | 4.4 | 4.84 | 5.324 | 5.865 | 6.451 | 7.096 | 7.806 |

| ACTUAL SIZE OF THE GLOBAL ISLAMIC FINANCIAL SERVICES INDUSTRY (US$ TRILLION) | 1.036 | 1.139 | 1.357 | 1.631 | 1.813 | 1.981 | 2.143 | 2.293 |

| SIZE GAP (US$ TRILLION) | 2.964 | 3.261 | 3.483 | 3.693 | 4.052 | 4.47 | 4.953 | 5.513 |

| GROWTH IN THE ACTUAL SIZE OF THE GLOBAL ISLAMIC FINANCIAL SERVICES INDUSTRY | 26 | 9.9 | 19.1 | 20.2 | 12.3 | 9.3 | 7.3 | 7 |

| AVERAGE GROWTH RATE BETWEEN 2009-2016 (%) | 13.89 | |||||||

| CATCH-UP PERIOD – BASED ON 10% GROWTH / POTENTIAL SIZE AND 13.89% GROWTH IN ACTUAL SIZE (YEARS) | 35.2 |

POTENTIAL1 AND ACTUAL SIZE OF THE GLOBAL ISLAMIC FINANCIAL SERVICES INDUSTRY

Political Conflicts and IBF

Outside these key markets, a substantial part of growth must come from greenfield expansion of IBF to maintain its momentum. However, a considerable part of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) block, especially the Middle East is in political turmoil. Libya, Tunisia, and to some extent Egypt, which were seen as emerging IBF markets in the backdrop of the so called Arab Spring, have not fulfilled expectations of the industry observers who predicted huge greenfield and brownfield expansion of IBF therein. The emergence of Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) has given birth to a crisis that has engulfed not only the Middle East but its adverse effects on anything to do with Islam in Europe.

Oil and IBF

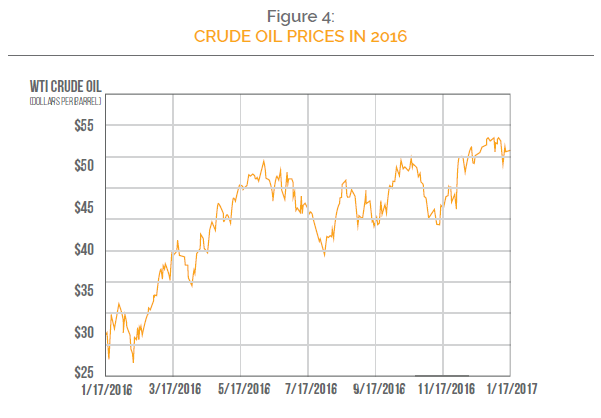

There is no doubt that growth in Islamic banking and finance (IBF) is closely linked with the oil prices. Given the historically low oil prices in the international markets, it is not unrealistic to assume that IBF will witness a slowdown in the key IBF markets, i.e., the GCC region.

Over 80% (US$1,877 billion) of the global Islamic financial assets are concentrated in the 10 countries with oil dependence (see Table 2). These countries’ public finances are likely to be most affected by the decline in the oil prices. Governments in these countries have often used Islamic finance to diversify their funding profiles but also to demonstrate their support for the growth and development of what is seen as an indigenous industry with many local stakeholders. Given the ambitious development plans, the governments are likely to continue to spend to support overall growth, but if oil prices fall further they may rethink their investment strategy and policies, which will inevitably have an impact on Islamic finance.

After a disastrous period of low oil prices, it appears as if the worst is over and the crude oil prices are going to settle between a more favourable US$50 to US$70 range in the years to come, the adverse impact of oil prices on IBF will be minimised (see Figure 4). This rather optimistic view on oil prices is despite the expected decline in China’s energy demand, Saudi Arabia’s increased oil pumping, and a possible flood of oil from Iran.

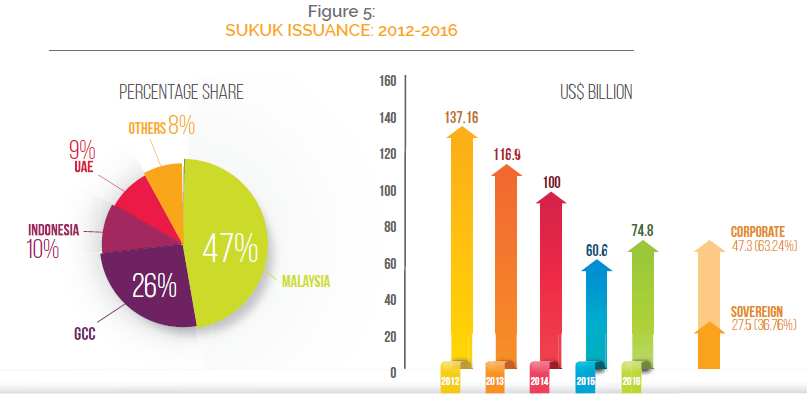

The signs of receding impact of low oil prices on IBF are evident from the increase in issuance of sukuk during 2016. The issuance of sukuk by the corporate sector was particularly remarkable. The global sukuk market resumed positive strides in 2016 after three years of consecutive decline following its peak in 2012. Country- and region-wise, Malaysia continued to be the largest issuer of sukuk last year with a share of 46.4% of the total, followed by Indonesia and the UAE, accounting for 9.9% and 9.0%, respectively. Other sizeable volumes came from Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Oman. Elsewhere, Turkey recorded notable growth in sukuk issuance at US$4.1 billion for the year, supported by a number of sovereign short- to medium-time issuances with maturity ranging from one to five years. Other notable issuers were Jordan, Senegal and Ivory Coast.

Total issuances of the GCC countries stood at US$19.6 billion in 2016, up from US$18 billion the previous year, mainly owing to higher government issuances. It points to the fact that sukuk remains an important funding source to balance out national budget deficits amidst low oil prices and shrunken export earnings (see Figure 5). Last year’s market was driven by corporate issuers mainly from the financial services sector, which accounted for 80.7% of total corporate issuances. The biggest corporate sukuk issuances were US$1.5 billion from IDB Trust of the Islamic Development Bank, US$1.2 billion from Dubai’s DP World, US$1 billion from Emirates Islamic Bank, US$500 million from Qatar’s Ezdan Holding Group and from several financial institutions in Malaysia.

However, a recent report by the IMF studied the correlation between oil prices and bank profitability as a result of the global credit crunch in 2008/09. The research revealed that the impact of the last oil price shock on banking profitability was invariably indirect with direct implications for some institutions with weaker risk management frameworks, more aggressive business models and poorer quality asset books. The study’s results suggested that the impact of oil price shocks was found to be greater with (non-Islamic) investment banks due to a variety of factors including a funding profile dependant on turbulent wholesale markets and revenues driven by trading income and transaction fees both of which are vulnerable to large market swings. Islamic banks typically have a more conservative business model and risk management framework while many source their funding from retail depositors making them less susceptible to fluctuations in the market.

It should be noted though that several Islamic investment banks suffered some of the same stresses of their conventional counterparts. Similarly, the reduction in oil prices is likely to impact conventional financial institutions as well as the Islamic ones. As such, the decline in oil prices will be a challenge that the Islamic financial services industry needs to closely manage. However, while the industry is still ‘young’ compared to its conventional counterparts, it is far more experienced now having had to weather several economic crises over the years while its regulators and professionals are more seasoned now, having more risk management and diversification tools that they can utilize than perhaps was the case 20 or 30 years ago. While many GCC states have been withdrawing global cash reserves from asset management institutions around the world, the need for this has often been driven by political developments as much as the impact of oil prices.

Growth in the Islamic finance industry may moderate in 2017, growing at a slower pace but will be to some extent counterbalanced by the opening up of Iran and more issuance from non-core markets such Europe, Russia, CIS countries and Africa. Growth is expected to pick up in the next decade. Iran could be a key market for growth as it emerges out of decades-old sanctions. Iran’s returned to the global market is expected to drive sukuk issuance as the country entire financial sector is Shari’a-compliant. Due to the sheer size of the country’s investment needs, the government will be looking at issuing sukuk as it shifts its funding needs to the capital market. Nevertheless, Iran needs to review is current legislation, which forbids sukuk trading in foreign currencies, if it wants to tap the international sukuk market. At the same time, Malaysia has always been a significant player in the global Islamic finance industry and often dominates global sukuk issuance volumes and yet it would be hard to argue that its economy is heavily dependent on oil prices.

The variation of petrol prices also would not just affect the Islamic banking industry specifically, but have a systemic effect on the entire banking field. The way in which a particular bank is run, including its type of investment portfolio, will have a large role to play in its success, rather than whether it opts for Islamic or conventional banking. Hence, it would be difficult, from a legal standpoint, to conclude that the Islamic banking system is in a more vulnerable position compared to the conventional one should there be a continued decline in oil prices.

Most oil-producing nations enjoy a stable legal structure that allows for the effective operation of Islamic banking structures side-by-side with conventional institutions. If the wider banking industry suffers from declining oil prices, presumably, policies of both legal and regulatory in nature would be formulated for the banking sector rather than just for conventional or Islamic banks specifically. On the flip side, Islamic banks are by nature, risk-averse. Given their prohibition against gambling, uncertainty and speculation, they are arguably better positioned to protect themselves against high-risk and volatile investments. The global economy remains in a difficult place due to the steep fall in oil prices, challenging global equity markets, high regional political tensions and continued reform of global financial markets. Islamic banks only seem more affected by this drop solely due to the fact that the majority of the concentration of Islamic banking takes place in oil-rich regions. Conversely however, the performance of Islamic banks in comparison to conventional banks during these times of crisis and as demonstrated historically, can be deemed more resilient due to more stable and conservative business models.

Western Financial Institutions and IBF

In wake of the heightened Islamophobia, Western banks and financial institutions continue to hesitate getting involved in IBF. While this is certainly a drag on the growth of IBF, it also provides an opportunity to the institutions in the Muslim world to tap key European markets where Muslims are significant in number. Exploiting the opportunity, Kuwait Finance House (KFH) launched a subsidiary bank providing full Shari’a-compliant banking services in Germany in 2015. The bank has gained a fully-integrated banking licence allowing it to accept deposits and offer full credit financing facilities in accordance with Islamic rules and regulations.

This followed the operations of its subsidiary bank Kuwait Turk, which has had maintained a small branch office in the German city of Mannheim for several years offering a range of Shari’a-compliant services to customers. The new German bank is based in Frankfurt, and operates under the name KT Bank AG and is a fully-owned subsidiary of Kuwait Turk. With about 4 million Muslims living in Germany, the bank plans to launch its European offensive from its German base. Its services will include sukuk deals, funds, real estate and investment portfolios. Habib Bank AG Zurich also plans to start offering Islamic financial services in the UK by the end of 2017.

Despite various claims by non-Muslim governments of being global or regional centres of excellence for IBF, the OIC countries remain leaders in terms of incidence of Islamic financial assets. In a list of top 20 countries in terms of Islamic financial assets, the UK is the only non-Muslim country that features significantly. The USA and European countries other than the UK have yet to receive attention and confidence of Islamic investors. Furthermore, notwithstanding attempts by European financial centres to attract businesses from Islamic asset managers, Saudi Arabia tops the list of domicile of Islamic funds in terms of AUM. Malaysia has for some time invested considerable amount of resources into Labuan to develop it as a jurisdiction of preferred choice for Islamic capital markets transactions and wealth management. Furthermore, Western (e.g., BNP Paribas) and other financial institutions (e.g., Nomura) based in Kuala Lumpur are performing far better in their Islamic businesses than their counterparts based in Europe. Dubai is also exploiting the opportunity by making itself as a global hub for Islamic economy. The efforts of Dubai Islamic Economy Development Centre (DIEDC) have started showing results.

Maturity of IBF

The slowdown in IBF may also be attributed to the maturity of Islamic financial markets in a number of countries where IBF has market share of one-fifth or more. It is quite natural for the industry to show sluggishness in these countries. This should also imply that there is a need to explore new markets to sustain growth in the industry.

A Demographic Analysis of Global Demand for IBF

There are an estimated 2.038 billion Muslims in the world but not all of them are bankable. Furthermore, no more than 20% Muslims world-wide are financially included. This means the potential pool of Muslims from which Islamic banks and financial institutions can draw their clientele does not exceed 400 million. Given the current global size of Islamic financial assets of US$2.293 trillion, Islamic financial assets per Muslim capita are estimated to be US$5,732.

That Will Drive Global Islamic Finance Industry

2017

Given this scenario, if all the Islamic financial assets were distributed equally amongst the bankable Muslims world-wide, they will individually hold no more than US$5,732. However, this is only hypothetical, as no more than 25% of the bankable Muslims are either interested in or are tapped by Islamic financial institutions. This implies that Islamic banks and financial institutions world-wide are chasing a pool of 100 million Muslim customers. Based on this 100 million pool, the Islamic financial assets per Muslim capita stands at US$22,930. Given this demography, financial inclusion is key to further growth of IBF. We estimate that by doubling the pool of Muslim customers to 200 million, the size of the industry will increase by 2.5 times to US$5.732 trillion.

An emphasis on financial inclusion will change the focus of IBF and its concentration in terms of incidence of Islamic financial assets. While at present, Islamic financial assets are by and large concentrated in the GCC countries and Malaysia, a successful financial inclusion policy will bring countries like Indonesia, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Turkey and Egypt into central focus. Therefore, large Islamic banking groups such as Dubai Islamic Bank (DIB), Kuwait Finance House (KFH) and Al Baraka Banking Group (ABG) must focus on these key markets as part of their strategy for future growth and expansion.

Interestingly, DIB already has strong presence in Pakistan and Indonesia but has not pursued its expansion plans into Turkey after opening a representative office in Turkey. Bangladesh and Egypt have not been on radar of DIB. KFH, on the other hand, has been in the Turkish market since 2002 when it established Kuveyt Turk Participation Bank. Although KFH has contemplated doing business in Indonesia since 2005/06, it appears as if its experience of going into Malaysia has discouraged it from pursuing the matter in the neighbouring Indonesia. KFH has also shied away from Pakistan, despite personal invitations from top leadership at the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP). It has taken a similar view on the Bangladeshi market. Egypt, however, has interested KFH in the recent past, when it showed interest in acquiring 99.9% stake of Central Bank of Egypt in United Bank of Egypt. Although the news was refuted by KFH, Egypt may in fact been on the waiting list of KFH’s expansion plans. The Al Baraka Banking

Group – the winner of the Strongest Islamic Retail Banking Group at Islamic Retail Banking

Awards 2016 – is perhaps the most aggressive Islamic banking group that has explored all the five markets listed above.

Leading Countries

The next chapter presents ranking of about 4 dozens of countries involved in IBF. Furthermore, Part 2 of the Report provides detailed analysis of the top 10 countries with respect to IBF. This introductory chapter asserts that Iran, Saudi Arabia and Malaysia remain central to the growth story of IBF on a global level. With Islamic financial assets of US$560 billion, US$431 billion and US$335 billion, respectively, they are three leading players in the global Islamic financial services industry (see Table 2).

With the lifting of economic sanctions on Iran, Iran has already started to become more visible in the global Islamic financial services industry. Iran’s central bank took chairmanship of the Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB) for the year 2017, a move that could help align practices in the country’s banking system with peers across Asia and the Middle East. It is expected that a number of meetings of IFSB during 2017 will take place in Iran, bringing the country into the fold of the global Islamic financial services industry. Malaysia and Saudi Arabia will continue to strengthen their positions in the global leadership of the Islamic financial services industry.

| COUNTRIES | |||||||||||||

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | FORMAL | INFORMAL | AVERAGE GROWTH | |

| (2007-2016) | |||||||||||||

| 235 | 293 | 369 | 406 | 413 | 416 | 480 | 530 | 544 | 560 | 542 | 18 | 12.70 | |

| 92 | 128 | 161 | 177 | 205 | 215 | 270 | 339 | 371 | 401 | 333 | 68 | 20.95 | |

| 67 | 87 | 109 | 120 | 131 | 155 | 200 | 249 | 254 | 335 | 289 | 46 | 20.89 | |

| 49 | 84 | 106 | 116 | 118 | 120 | 123 | 144 | 157 | 197 | 167 | 30 | 18.58 | |

| 63 | 68 | 85 | 94 | 95 | 103 | 105 | 107 | 115 | 121 | 99 | 16 | 8.12 | |

| 17 | 21 | 18 | 18 | 20 | 21 | 25 | 27 | 32 | 43 | 35 | 8 | 7.49 | |

| 21 | 28 | 35 | 38 | 47 | 68 | 70 | 111 | 122 | 130 | 123 | 7 | 28.11 | |

| 16 | 18 | 22 | 25 | 35 | 41 | 43 | 69 | 80 | 81 | 73 | 8 | 24.41 | |

| 18 | 19 | 24 | 27 | 33 | 37 | 40 | 43 | 55 | 61 | 41 | 20 | 13.47 | |

| 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 22 | 25 | 49 | 51 | 66 | 66 | 0 | 56.06 | |

| 6 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 13 | 17 | 19 | 21 | 26 | 31 | 21 | 10 | 20.00 | |

| 6 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 12 | 19 | 19 | 20 | 25 | 31 | 19 | 12 | 20.39 | |

| 5 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 21 | 24 | 18 | 6 | 18.68 | |

| 6 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 16 | 18 | 23 | 19 | 4 | 17.55 | |

| 3 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 17 | 19 | 15 | 4 | 27.98 | |

| – | 4 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 23 | 25 | 9 | 16 | 24.44 | |

| 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 18 | 21 | 15 | 6 | 25.48 | |

| 2 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 43.57 | |

| OTHER COUNTRIES | 27 | 32 | 51 | 57 | 170 | 331 | 327 | 200 | 210 | 120 | 61 | 59 | 49.25 |

| TOTAL | 639 | 822 | 1,036 | 1,139 | 1,357 | 1,631 | 1,813 | 1,984 | 2,143 | 2,293 | 1,948 | 339 | 17.82 |

ISLAMIC FINANCIAL ASSESTS IN SELECTED COUNTRIES (US$ BILLION)