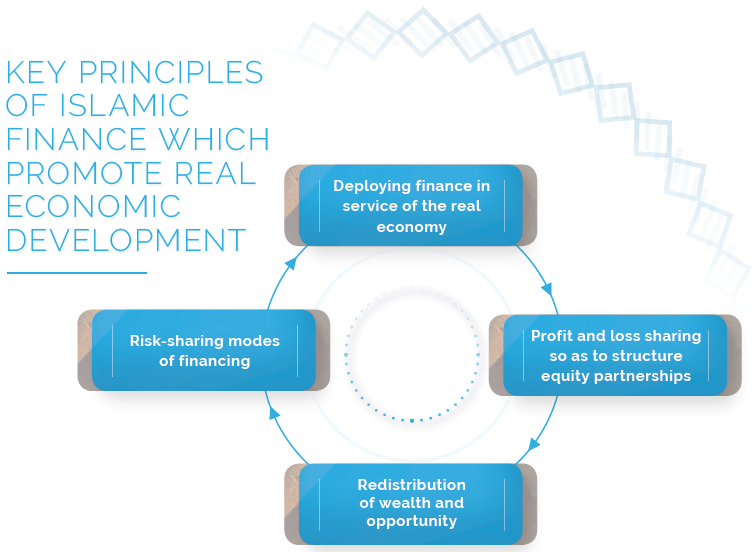

With resilient growth, effective risk mitigation and participative modes of financial products; Islamic finance promises to play a significant role, especially in the Muslim world. The key principles of Islamic finance such as responsibility and sustainability coupled with enhancement in Fintech, contributes to higher and more inclusive economic growth while at the same time promotes macroeconomic and financial stability. As a form of financial intermediation, Islamic finance offers tremendous potential in reinforcing links between finance and the real economy.

Risk-sharing shifts the emphasis from the creditworthiness of the borrower to the value creation and economic viability of investments that create new wealth. Islamic finance also promotes the availability of socioeconomic tools that could help improve financial access and foster financial inclusion as it provides formal financial services to Muslims who have previously remained largely underserved by the traditional financial system due to religious reasons. With greater emphasis on profit and loss sharing, Islamic finance encourages the provision of financial support to productive enterprises that can increase income, generate jobs and subsequently help in poverty reduction.

Role of Islamic Social Finance in Sustainable Development

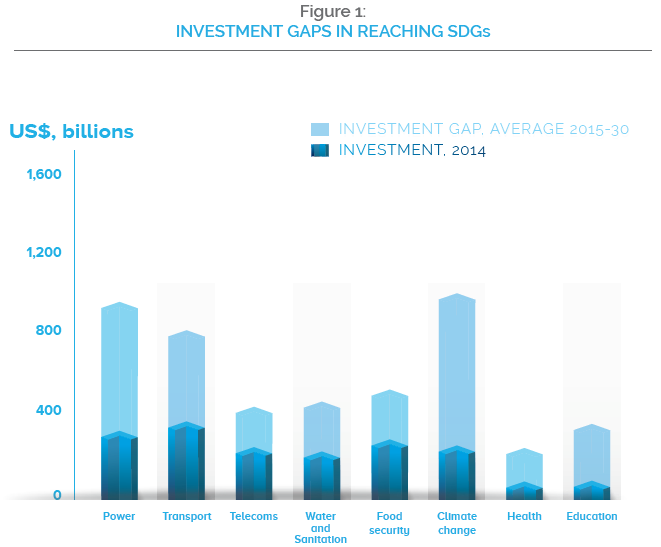

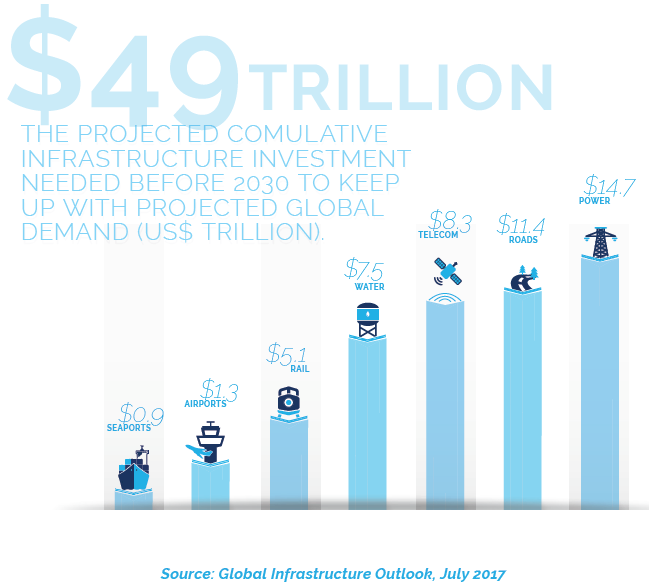

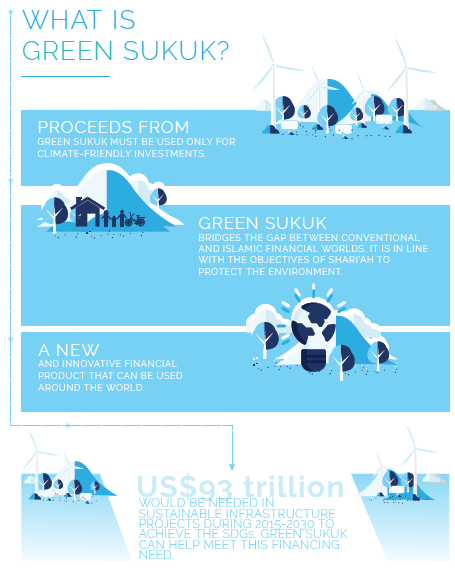

The realization of the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) rests on infrastructure development, inclusive growth, employment creation, environment-friendly technological advancements and business processes re-engineering. All of these are not going to be possible without substantial mobilization of funds. According to some estimates, around US$3.5 trillion to US$5 trillion is needed every year to make desirable progress on SDGs. At the global level, investment in infrastructure is estimated to be around US$100 trillion over the next two decades.1 McKinsey estimates that US$93 trillion worth of investments would be needed in sustainable infrastructure projects during 2015-2030 to achieve the SDGs, with the bulk going to the energy sector (US$40 trillion or 43%), followed by transport (US$27 trillion or 29%), water and waste (US$19 trillion or 20.4%) and telecommunications (US$7 trillion or 7.5%).

In the Middle East, there is immense potential to use solar energy alongside oil. There is also a strong case for wind power in some other corners of the region, such as Morocco. However, lack of financing is one of the major obstacles for the development and use of renewable energy in developing countries. This is because financial sectors of developing countries are often underdeveloped and are unable to efficiently channel loans to renewable energy projects. In terms of infrastructure, World Bank figures estimate that developing countries spend around US$1 trillion a year on building infrastructure. An additional US$1 trillion to US$1.5 trillion will be needed through 2020 in areas such as water projects, desalination plants, power projects and transportation projects. Emerging Asian economies alone, as estimated by Asian Development Bank, will require some US$8 trillion over the next decade to satisfy the growing demand in the areas of energy, water and transportation.

Clearly, governments in developing countries have much more distance to travel in achieving the SDGs targets. Yet they generally have weak tax base to work with. Since the gap to fill in underdevelopment is huge in the case of most of the Muslim-majority

countries, it is important that all-encompassing efforts are undertaken involving various institutions to make the leap forward. Islamic institutions, which have a socioeconomic character, can also be employed in creating synergistic efforts towards achieving the development objectives, especially in Muslim-majority countries.

There is much potential for Islamic finance to promote sustainable economic development through such approaches as widening access to finance (including microfinance), financing infrastructure projects, and expanding the reach of takaful (Islamic insurance). Given its social and ethical principles and emphasis on risk-sharing and asset-backed financing, Islamic finance has untapped potential as a substantial and non-traditional source in contributing to the achievements of the SDGs. As part of its commitment to the SDGs, the Islamic Development Bank (IDB) has announced that it will increase its funding of SDGs-related activities through its ten-year strategy framework from US$80 billion to US$150 billion over the next 15 years (2016-2030). As per IDB, innovative Islamic financial instruments, especially for infrastructure development such as sukuk, can be used to mobilize resources to finance water and sanitation projects (SDG-6), sustainable and affordable energy (SDG-7), build resilient infrastructure (SDG-9) and shelter (SDG-11).

In recent years, Socially Responsible Investment (or SRI) sukuk and green sukuk have been paving the way towards more climate-friendly investments in support of the SDGs. For instance, the International Finance Facility for Immunization Company (IFFIm) issued sukuk to fund immunization programmes in the world’s poorest countries through Gavi or Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization. This is in support of SDGs number 3 aimed at “good health and wellbeing” for all. While the Khazanah SRI sukuk, where proceeds are used to fund the rollout of Trust Schools Programme, promote SDGs number 4, which regards “quality education” as the foundation to improving people’s lives. In 2017, Malaysia launched the world’s first green sukuk – a collaboration between Malaysia’s central bank and Securities Commission, together with the World Bank. This was regarded as a big step forward to fill gaps in green financing and contributing to SDGs, especially number 13 on “climate action”, and numbers 14 and 15 concerning “protecting animal and plant life in the seas and on land”.

Other Islamic finance instruments such as zakat, waqf, takaful and Islamic microfinance can be utilized towards pursuing the fulfilment of SDGs. For example, zakat and waqf-based microfinance institutions can be used to serve the social sector.3 Real estate-based waqf can generate proceeds through the rental of properties, which then can be used to finance social development needs. Meanwhile, cash and commodity-based waqf can provide interest-free loans (qard hassan) to the needy in sectors like education, health and agriculture. Micro takaful, on the other hand, can be an effective and efficient vehicle to provide protection for the poor and thus, enable the achievement of sustainable poverty alleviation.

In Egypt, the Ministry of Social Solidarity introduced a new conditional and non-conditional cash transfer programme called “Takaful & Karama” (Solidarity & Dignity). Implemented across the country, the programme aimed at strengthening the social safety nets of the poorest households and the most marginalized people. Under the takaful programme, children’s human development is promoted through health- and education-related conditional cash transfers. Income supports were given to families with children conditional upon school enrolment, on 80% school attendance for children ages 6–18, on medical check-ups for mothers and children under 6, and on attending nutrition classes Karama, instead, is aimed at promoting social inclusion among elderly people and people with disabilities, through an unconditional cash transfer. The Takaful & Karama programme was developed based on the latest technologies and innovative tools to ensure that the poor receive their cash transfers as fast as possible and in an accurate manner.

Role of Zakat in Sustainable Development

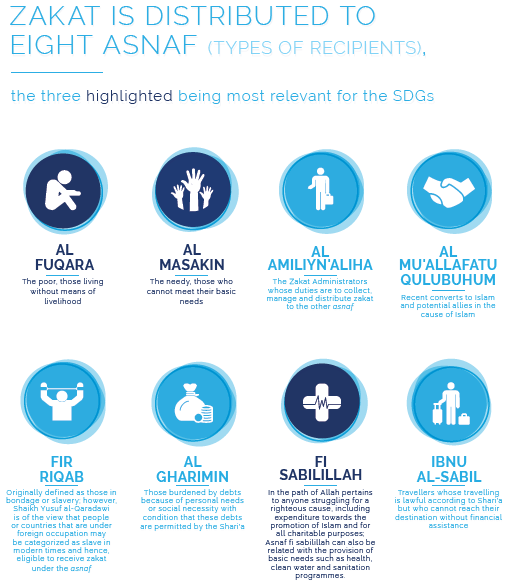

Zakat is an obligatory payment for all Muslims earning above a certain threshold. Although zakat can be considered as one of the world’s largest forms of wealth transfer to the poor, it has been mostly overlooked by development organizations despite its tremendous potential for contributing to the achievement of the SDGs. Under the institutions of zakat, the payer and receiver of zakat belong to two different income classes. The payer of zakat is non-poor with surplus wealth above nisab, which is the minimum amount of property or wealth that must be owned by a Muslim before he/she is obligated to pay zakat. On the other hand, the receiver of zakat is usually a poor person with no surplus wealth above nisab. Thus, the threshold wealth of nisab makes a distinction between the payer and receiver and helps to achieve targeted income and wealth transfer to the poor and needy. Since this redistribution is based on wealth rather than income, it can achieve the redistribution objectives more effectively and consistently as wealth fluctuates much less than income over the business cycles. Since zakat has an inbuilt mechanism to reach the right targets in terms of zakat collection and disbursement, it ensures that the very poorest of society who lack even basic essentials are protected from hunger and financial insecurity, as per the SDGs.

Furthermore, the accumulated wealth can be much more than a single period income, especially in high net worth individuals of the society. That is why, in the absence of broad-based wealth taxes and the existing loopholes in taxing off-shore wealth, the progressive income taxes alone have been unable to reduce income inequality and achieve a more equitable wealth redistribution. In the US, for instance, the progressive taxes were designed to reduce income inequality. But during the last four decades, while the share of income taxes levied on the upper tenth of incomes rose 15%, the after-tax income share of the remainder of incomes declined by 13%.

Oxfam reports that 8 individual persons with a combined wealth of US$426.2 billion as of end-2016, have as much wealth as the bottom 50% of the entire global population.4 As per World Bank, there are 767 million people living below the poverty line of US$1.90 per day. This translates into a poverty gap of US$531.9 billion (1.90 x 767,000,000 x 365) per year. Comparing the wealth owned by the richest 8 persons (US$426.2 billion) and the total global poverty gap funding requirement (US$531.9 billion), it is clear how redistribution of wealth can help in pooling poverty alleviation funds. With global wealth reaching US$255 trillion, it is enough to give 767 million poor people US$1 a day for 910 years. However, only a single year of 2.5% zakat on this amount will give 767 million poor people US$1 a day for 23 years.

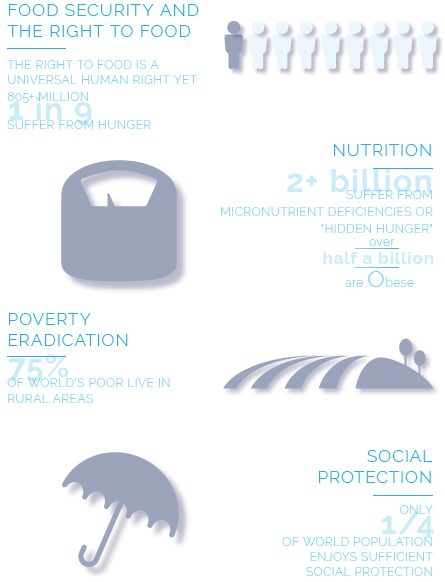

According to the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), there are approximately 800 million people who suffer from hunger and who are food insecure in their routine lives. Most of the poor countries lack basic resources to kick-start growth and to invest in health and education. Thus, the redistribution of resources is vital to enhance income as well as the capacity to earn sustainable incomes; both requiring income support programmes, basic health and education as well as microfinance to build small enterprises. The Hunger Project estimated that about 2.4 billion people do not have adequate sanitation and nearly 1,000 children each day die due to preventable water and sanitation-related diarrheal diseases. This is partly because sanitation business is not as good as cellular services and life’s other comforts and luxuries. Interestingly, for the world as a whole, per capita food supply rose from about 2,200 kcal a day in the early 1960s to more than 2,800 kcal a day by 2009.5 The institution of zakat could help in providing income support to the poor people who are food insecure due to lower and unsustainable incomes.

Statistics shows that nearly 50% of the people living in extreme poverty are 18 years old or younger, which means that a significant portion of the global population would not have a fair start in achieving socioeconomic mobility. Thus, proper nourishment, basic medicines and vaccinations are necessary to avoid ill-health, stunting and loss of capacities for independent productive living in adulthood. Unless effective redistribution happens, the purchasing power cannot be enhanced, which is vital for the affordability of even the basic necessities of today such as food, water and medicines. Providing quality education is vital for achieving permanent poverty exit, enhancement of skills and capacities, and to ensure upward social mobility. Mosque-based schools in the Muslim majority countries, for example, effectively channel zakat funds to ensure basic religious and secular education. Hence, effective administration and management of the zakat funds can help in scaling up the benefits in terms of strengthening institutions to create synergistic effects. Economic growth is necessary to realize sustainable reduction in poverty and in ensuring upward socioeconomic mobility. On one hand, zakat from endowment surplus households (those having higher wealth than nisab) to the endowment deficient households can help in providing income support and affordability for skills enhancement programmes. Zakat could also be used to provide funding for education and health institutions, thereby contributing to human capital development, which in turn can provide decent work. On the other hand, the institution of zakat would ensure circulation of wealth in the productive enterprise, thereby directing capital to the real sector of the economy rather than sitting idle in the hands of wealthy individuals. As such, zakat has the potential to help address global inequality.

Role of Waqf in Sustainable Development

Waqf is an important social institution in the Islamic framework. In the institution of waqf, an owner donates and dedicates a movable or immovable asset for the perpetual societal benefit while beneficiaries enjoy its usufruct and/or income perpetually. Waqf can be established either by dedicating real estate, furniture or fixtures, other movable assets and liquid forms of money and wealth like cash and shares. The institution of waqf can be used to provide a wide range of welfare services, such as educational institutions, health institutions, environmental preservation programmes and financial institutions like waqf-based microfinance and socially driven banks. For instance, cash waqf can pool more resources and ensure wider participation of individual donors in order to build institutions, such as schools, hospitals, and orphanages. Unlike zakat where funds must be utilized for specific categories of recipients, waqf provides flexibility in fund utilization.

Along with income support and cash transfers, poor people also require skills and productivity enhancement in order to get out of poverty and achieve social mobility. Lack of finance and business training requires institutional support to unleash the potentials of micro-entrepreneurs and to establish viable micro-enterprises.6 Growth-oriented microfinance programmes also need to provide training, insurance, and skills enhancement facilities.7 In this regard, the institution of waqf can improve the chances of socio-economic mobility by providing a rather permanent, effective and efficient funding source for the health and education infrastructure. The increased and improved provision of education and health infrastructure funded through waqf can enhance the income-earning potential of beneficiaries.

Financial Inclusivity through Islamic Finance

On average, only 28% of adults in OIC countries hold a bank account at formal financial institutions. This is lower than the 30% average for middle-income countries and 93% average for the high-income countries.8 Part of the reason is Muslims’ voluntary exclusion from interest-based financial services. About 7.7% of the poorest 40% people in OIC countries borrow from financial institutions, which is lower than the average of the poorest 40% people in low-income countries. Most borrowings are from informal sources such as family and friends, suggesting that the strength of social institutions compensates financial sector underdevelopment. In the OIC countries like Guinea-Bissau, Gabon, Chad, Sudan, Syria, Mozambique, Gambia and Iraq; microfinance outreach is not even catering to the 1% of the poor people.

Even for middle-income households, there is substantial unmet demand for consumer durables financing. The purchase of durable goods like house and automobiles require substantial resources, which most people are not able to generate solely through their periodic incomes and savings. For them, bank financing is the best option for such purchases. A study conducted Countries”, Islamic Development Bank. by Shirazi using UN-Habitat 2006 methodology suggests that the IDB member countries need around 8.2 million houses per year to accommodate poor and low-income urban people.9 This translates into nearly 22,421 dwellings per day in order to accommodate the expected urban population growth. Thus, presenting a challenge as well as an opportunity for Islamic banks to increase their outreach by extending their product lines and geographical presence towards fostering inclusive finance in OIC countries.

Opportunities with Fintech for Islamic Economics and Finance

Islamic finance can help in enabling access to financial services for people who have abstained from conventional banking services for religious or ethical reasons. But the key question is can Islamic finance also provide access to financial services to the bottom of the pyramid population. Financial inclusion of the poor requires a different approach in product design, pricing and delivery. It requires innovation, flexibility, efficiency and committed leadership. Islamic microfinance is yet to take big strides even though Islamic finance gives due emphasis to egalitarian financial structures and products in the Islamic economics and finance literature. To this effect, Fintech offers an opportunity for Islamic financial institutions to efficiently reach potential clients. Fintech can help in increasing Islamic finance outreach in regions where the brick-and-mortar model of delivery is not be financially sustainable.

In product structures, Fintech can assist in organizing completion of different steps involved in a typical Islamic finance transaction. A key issue remains whether Fintech would be welcome by Islamic banking institutions where Shari’a Compliance Auditors prefer more control and personal oversight in order to reduce Shari’a non-compliance risk. But it remains to be seen whether Fintech increases or decreases Shari’a non-compliance risk. To materialize the benefits of Fintech, it is important that there should be standardization in Shari’a rules so that there is greater scope of automation for integrating Fintech in product design and delivery. If Shari’a compliance can be done more efficiently with Fintech without requiring the day-to-day approval of Shari’a advisors, then it will be a welcome development and will bring cost efficiencies to Islamic banking. Furthermore, Fintech can help in cross-selling of financial products in Islamic banking, which can lead to economies of scope through integrated service delivery assisted by technology.

Fintech, by default, will inevitably disrupt the traditional ways of conducting banking businesses and transactions. Islamic banks need to step up its adoption of Fintech as this would make the financial markets more competitive by enabling peer comparison and performance analysis at the fingertips of the consumers. Fintech might increase commercial displacement risk for Islamic banks that fall behind in integrating Fintech in their operations due to high cost or small-scale operations. With more than 400 million people in Africa remains unbanked, Fintech provides an opportunity to reach them cost-effectively. The same is the case with many Muslim-majority countries where financial exclusion is significant. For instance, less than 20% of the population in Pakistan has bank accounts. Thus, Fintech can be a key catalyst in increasing the penetration and outreach of Islamic banking in Muslim-majority countries.