FinTech has established itself as an increasingly transformative force within the financial services sector across the world. But even as the word itself is now on virtually everyone’s lips, there is yet a clear consensus on the exact definition of FinTech. At the most basic level, it involves the application of technology (above all information and communications technology) to the way financial services are structured and delivered. Opinions differ as to what kind of technology qualifies, with some observers insisting that FinTech is inherently a dynamic, innovative force driven by – and in turn causing – disruptive change. For instance, Wikipedia terms it as “the new technology and innovation that aims to compete with traditional financial methods in the delivery of financial services.” Nonetheless, one could argue that the ATM was an early example of FinTech.

We have witnessed how FinTech has fundamentally transformed the traditional banking model. By enabling people to use basic banking services at all times and at a far greater number of locations, it overcame the limitations of branch opening hours and numbers. FinTech delivers superior convenience, greater flexibility, increased speed, and less waste. What initially was a compliment, it ultimately became a substitute to conventional branches. Internet banking is a more recent example of similarly empowering innovation as are point of sales machines at retail shops.

Interestingly, while ATMs could disrupt, they have also in many cases empowered existing institutions, for instance allowing banks to serve their customer base better and achieve a greater impact. The same is true for some more recent FinTech innovations. The relationship between innovative FinTech firms and established financial sector incumbents is therefore by no means always competitive or confrontational. Rather, more and more established financial intermediaries see FinTech as desirable, indeed necessary, and are keen to proactively contribute to its development and to benefit from it.

With the financial sector undergoing fundamental structural changes since the onset of the global financial crisis in 2007/08, the regulatory burden facing financial institutions has increased dramatically. This has now reached a point where the investment industry is frequently struggling to achieve a rate of return that exceeds its cost of capital. In other words, the established banking model has come under a potentially existential threat. This is forcing financial institutions to profoundly examine their organization and business models. At the same time, the rise of FinTech is benefiting transformative changes of the “supply side” of technology.

The pace of progress within information technology and digitization is ever accelerating as the proverbial Information Highway established itself more and more firmly at the heart of modern economic infrastructure. The impact of innovations such as big data and artificial intelligence is making itself felt with a growing impact across the spectrum of financial services, often with profoundly transformative consequences. Furthermore, the increased popularity of FinTech is encouraging company formation and drawing more and more entrepreneurs to this area. This can be expected to translate into a rapidly increasing supply of new ideas and solutions with potential applications for improving the delivery of financial services.

As financial institutions grapple with the new pressures and challenges of regulation, changing tastes, and disruptive technological change; FinTech is almost invariably integral to the answers that emerge. This is boosting the demand for FinTech innovation across geographies and in all segments of financial services. These emerging solutions are helping companies achieve savings of time, reducing their reliance on labour-intensive processes, and allowing increased transparency as well as greater accuracy. The desire to reduce the costs associated with regulatory compliance is another important driver. Some companies have been able to overhaul key elements of their operations, while others have revamped their entire business models, in their pursuit of efficiency gains and, ultimately, better financial results. The rise of new technologies is fragmenting value chains and is making it increasingly attractive, as well as technically feasible for financial institutions to outsource many of their non-core functions. It is widely expected that some of these will be provided by centralised utility-like institutions in the years ahead. The cost competitiveness of these facilities will in turn be driven above all by technology.

These ongoing efforts to harness digital technology have effectively opened up a new frontier in the evolution of modern finance. While this journey is still at a relatively early stage, few doubt that it will eventually amount to a fundamental paradigm shift with the potential to reshape the entire sector. Under the circumstances, FinTech, however new and exotic it may still seem to be to some, is unlikely to be an optional luxury. Rather, now is the time to embrace this wave of change and make it an integral part of future planning by all financial institutions.

Investment in FinTech

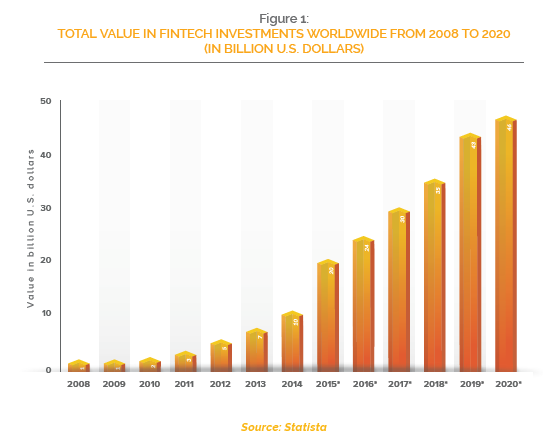

While some countries have made greater strides in the area of technological innovation and its financial applications than others, there is no doubt that FinTech is now a global phenomenon. This rising tide of innovation is now also sweeping across the geographies that gave rise to modern Islamic finance, namely the GCC and Southeast Asia. A number of jurisdictions have made – or are making – concerted, proactive efforts to foster the creation of a local Fin- Tech industry through regulatory initiatives and support to dedicated physical spaces designed to serve as FinTech clusters. Malaysia led the way in setting up a light-touch regulation sandbox for FinTech innovation. Since then, similar initiatives have been undertaken in the Gulf by the Central Bank of Bahrain, the Dubai International Financial Center, and Abu Dhabi Global Market. These trends are not only likely to continue but will almost certainly accelerate.

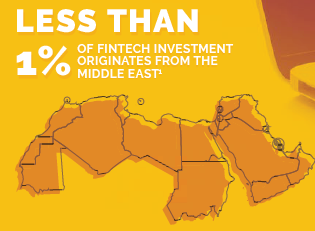

Until recently, however, the progress of FinTech has proven comparatively slow in some of these “home jurisdictions” of Islamic finance, especially the Gulf, as compared to most other parts of the world. Total FinTech investments in the Gulf and the Levant were estimated at US$45 million during the six-year period between 2010 and 2015. The total for Southeast Asia (exc. Singapore) was almost eight-fold at US$345 million. Singapore alone boasted more than three times the Middle East at US$167 million. By comparison, FinTech investments in China and India totaled US$3.5 billion and US$2.2 billion, respectively. The US was the largest market with an aggregate of US$31.5 billion – 700 times the Middle East tally. The UK and Europe reached US$9.8 billion. In other words, FinTech investment in the Middle East represented at best the proverbial drop in the ocean as compared to geographies at the forefront of driving these changes

This major disparity is likely reflective of the fact that the GCC financial sector has, at least until recently, been able to benefit from a robust growth momentum from more “traditional” drivers. This has been thanks to an unprecedented pipeline of infrastructure investments as well as continued rapid population growth. All of this has driven steady increase in financial sector assets. At the same time, conservative regulation has helped ensure financial sector stability, including often comfortable buffers that have made the pursuit of new sources of efficiency less urgent than in more saturated and leveraged markets. Under the circumstances, the kinds of pressures that have driven the creation of the industry in the West have been less pronounced in the Middle East. When banks have been able to meet their objectives without significantly modifying their business models, the incentives to proactively embrace disruptive innovation have been correspondingly more limited.

Similarly the supply-side forces have tended to be weaker. The resources available for research and development have tended to be more limited in the Middle East where the links between academia and the industry are generally much weaker than in the West. Similarly, the demand for innovation on the part of the corporate sector has been curbed by an essentially extensive economic growth model, relying of factor accumulation rather than productivity. However, the operating environment has become more challenging following the drawn-out period of lower oil prices since the late 2014 and a multi-year fiscal overhaul all the regional governments have committed themselves to. In response to these trends, the need for greater productivity and greater innovation is likely to increase significantly.

Perhaps not coincidentally, there has been a palpable increase in the interest in disruptive technological change in the region. Especially in 2017, something of an inflection point in the journey toward a local FinTech ecosystem appears to have been reached. The change has been particularly pronounced in the GCC where both regulators and market participants have become far more active – indeed proactive – in the area of FinTech. Recent months have seen an unprecedented push for new regulations in areas such as crowdfunding/crowdsourcing. Moreover, incumbent financial institutions across the region have begun to embrace FinTech and are in the process of channelling significant investments into technical innovation.

What is Islamic FinTech?

FinTech is now clearly emerging as an increasingly potent force in reshaping the financial sectors in most Muslim-majority countries. But what does this mean specifically for Islamic finance? And at what point does it become appropriate to speak of Islamic FinTech? Technology, of course, is inherently agnostic and typically just a delivery mechanism, the means to an end rather than an end itself. While financial products can be labelled as Shari’a-compliant or not, it is less obvious that the same is true for financial technology. What is more obvious is that, properly leveraged, FinTech can allow Islamic financial institutions to become better at pursuing their principles-based objectives. Moreover, by boosting transparency, increasing efficiency, and reducing costs; FinTech should make it possible for Islamic financial institutions to become more inclusive by reaching more customers at a lower cost and less risk.

While Islamic financial institutions can in most cases benefit from technological innovation, their ability to do so is not inherently different from that of conventional institutions. Better market access and margins is not a greater achievement for an Islamic bank than it is for a conventional one, even if it serves as a potentially important catalyst for living up to the principles of Islamic finance. Of course, the relative complexity of Islamic products means that achieving cost savings is perhaps a little bit more critical for Islamic institutions, since their costs tend to be slightly higher to begin with. At the end of the day, the transformative impact of FinTech is likely to prove broadly comparable across market segments.

It thus seems appropriate to wonder whether there a dimension of Islamic FinTech that goes beyond the agnostic enabler and allows Islamic finance to become not only more cost-effective but fundamentally more Islamic. In other words making Islamic finance truer to its underlying principles. Instead of enabling the existing delivery mechanisms of Shari’a-compliant financial services to work more efficiently, can FinTech be leveraged more holistically to design models and structures that are more fundamentally in keeping with the Shar’ia? Moreover, can it then be utilized to allow these products to be distributed more efficiently than has been the case in the past? The answer to these questions is clearly affirmative. FinTech has the potential to deliver direct, rather indirect or derivative benefits to Islamic finance. However, it is far less clear how swift or truly transformative progress will prove. This is likely to depend on the willingness and ability of Islamic financial institutions to proactively embrace FinTech and drive its evolution in line with the industry’s aspirations.

Truer Risk Sharing?

The reason Islamic FinTech should hold particular potential for Islamic finance goes back to a long-standing dispute on how effectively the traditional banking paradigm has served the needs and aspirations of Shari’a-compliant finance. Conventional finance has become a highly regulated framework for channeling capital with minimal – indeed deliberately managed – risk to end-users with an established track record. By contrast, genuine risk-sharing remains an objective at the heart of Islamic finance. The fact that most Islamic financial institutions have to date operated in a marketplace created for the needs of (and typically regulated from the perspective of) conventional finance has arguable forced Islamic finance into an inherently reactive posture.

In order to remain competitive or win market share, Islamic finance has often mimicked conventional products and structures in ways that have triggered widespread complaints of “Shari’a wrappers” – products that are Islamic in appearance but conventional at heart. In some cases, innovation has led to accusations of “Shari’a shopping” when Shari’a-compliance has been viewed as the means to an end (better tapping a Shar’ia-sensitive clientele) rather than the end itself. Whatever the ultimate merit of these claims, they do underscore the widespread perception that there is often limited differentiation between Islamic and conventional banking or other financial services. At the same time, even in Muslim-majority jurisdictions that championed the rise of modern Islamic finance, Shari’a-compliant assets tend to represent a minority – albeit sometimes a significant one – of financial assets.

What seems increasingly clear, however, is that the rise of FinTech now presents fundamentally new opportunities for delivering Islamic capital to those interested in using it. Some of these models have the power to transcend the limitations of the conventional banking paradigm. For instance, the rise of Shari’a-compliant crowdfunding promises a mechanism that reflects the spirit of risk sharing and creates new channels for capital to flow from providers to entrepreneurs with projects that require funding. An example in point is Malaysia’s Investment Account Platform, which brings together multiple financial institutions and potential projects seeking funding. By improving the availability of and quality of information and reducing costs, FinTech can potentially bring about more efficient markets through better aggregation and matching. This should permit a more decentralized form of financial intermediation. It can thus potentially connect more fully between the demand for and supply of capital than the more centralized, established banking model.

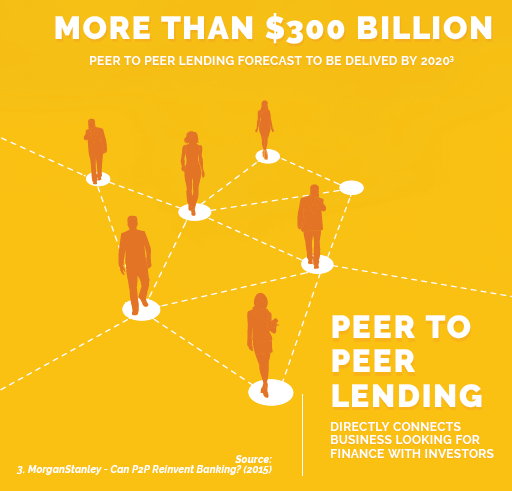

After all, projects that may not hold appeal to banks may be attractive to some individual investors or institutions. Risk appetites differ but the range is deliberately restricted through regulation in many established areas of finance where this serves the objectives of fiduciary duty and macro-prudential stability. For informed and experienced investors, crowdfunding and comparable mechanisms can become a way to a tap a broader range of opportunities and to deliberately include social and charity-related objectives in their decisions. Globally, the evidence of the potential of peer-to-peer lending as a way of boosting access to capital is compelling. In 2009, nine major platforms raised US$10 million globally. This had risen to a total of US$767 million in 2016.

Improved access to information should also create more efficient markets by permitting easier comparability and further contributing to the ongoing standardization of key Shari’a-com- pliant structures. It is widely accepted that the fragmentation of the Islamic financial marketplace has been an important source of inefficiency and cost. This in turn has almost certainly curbed its growth. In general, by boosting transparency and access to information, FinTech can contribute to greater standardization and harmonization of Islamic financial products. Access to information and more comprehensive documentation can also permit easier filtering out of practices and investments or structures that investors deem objectionable.

Better Risk Management?

Perhaps the greatest potential of FinTech for creating win-win solutions comes from its ability to meet key regulatory objectives without imposing costly regulatory burdens, or at least without relying exclusively on formal regulation. While risks can be managed through regula- tory restrictions, they can also in principle be dealt with through transparency and analytics. A lack of accurate information as well as information asymmetries are important sources of risk. As such, regulation is frequently a direct response to them. From an economic perspective, devising solutions that efficiently meet regulatory objective through better product and process design is likely to be more efficient. With sufficient access to accurate data, investors can make informed investment decisions in line with their own profile and appetite. Products that do not pass screening are immediately left out. Conversely, risk-prone investors can do more than they would have been able to under the traditional paradigm of intermediation. Again, access to information can serve as a mechanism of helping them understand the risks and their potential implications. This could potentially reallocate an element of risk management from the regulator to the investor who is better equipped to assume responsibility for his choices.

FinTech has already brought about transformative change in the area of fostering efficiency through greater transparency and effectively eliminating the margin of error or deliberate data/record manipulation in some key areas. By enabling more accurate documentation and data gathering, FinTech can eliminate or at least reduce risks emanating from inaccuracies and errors. To wit, BlockChain, which is a distributive ledger, creates an ongoing and unalterable digital record of transactions. This process is more efficient and safer, ie less risky, than anything that preceded it. Once an immutable digital record of a transaction is created, no one can modify or delete it. This is a fundamental paradigm shift from the thrust of formal regulation in recent years because it means that greater transparency and lower risk is achievable without increased institutional centralization or more aggressive regulatory intervention. Blockchain might even offer opportunities to manage transactions between institutions that subscribe to different Shari’a interpretations.

These qualities ultimately mean that FinTech can in many areas provide a market-based way of achieving many of the objectives that have to date been pursued through regulation. Indeed, we may be nearing a point where market transparency and reliability are more likely to be achieved through FinTech than through conventional, costly disclosure and reporting requirements. This is an ultimate win-win where a market solution can both create value and satisfy the regulators. If FinTech can significantly reduce the costs of this kind of transparency and improve access to operative, actionable information and analytics; it can potentially enable consumers and intermediaries to undertake some tasks that now rest primarily with regulators. This could also allow regulators to reallocate some of their resources from ex-ante regulation to more ongoing market supervision, which technological innovation should allow them to under-

take more efficiently and accurately. Not only could this create an additional source of savings for intermediaries and even regulators, but it would also put in place a sustainable mechanism for genuine risk sharing by allowing all concerned to make informed decisions.

While these innovations are not within the exclusive purview of Islamic finance, they do have a particular resonance with the values of Islamic finance and should therefore be particularly appealing to the industry. Indeed, it is quite possible that FinTech at its core is “more Islamic” than the standard banking model. While the ultimate impact of these innovations on Islamic finance is difficult to determine at this point, the potential for profound changes seems rather obvious as more decentralized capital pooling and allocation mechanisms could well reduce the relative importance of formal banks within the sector. Many of the successful digitized financial platforms, such as PayPal are not banks, although they can perform some of the same functions. Non-bank service providers now often provide superior speed and convenience along with lower costs.

Achieving Greater Social Impact

FinTech can in principle serve as a powerful tool of economic empowerment. The fact that financial services are delivered at a cost (which is invariably further increased by regulation) has inevitable negative implications for access. In all markets, but especially in developing economies with a significant proportion of poorer people, formal financial intermediation is rationed to a degree as a result. By reducing the cost of financial intermediation and regulation alike, FinTech can bring formal financial services within the reach of new segments of the population. Far beyond empowering through improved access, this can also help eliminate costly, risky and inefficient informal financial service solutions and ultimately boost inclusion, economic development as well as living standards.

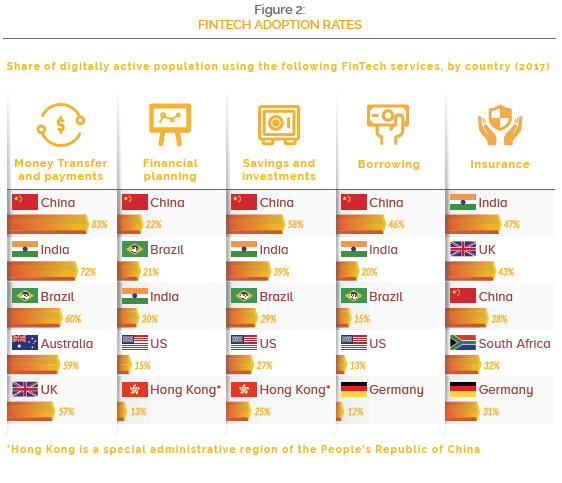

Mobile payments and electronic transactions have gained immense popularity in many developing economies where they can be delivered at a fraction of the cost of traditional banking. This is partly because the costly infrastructure associated with formal banking is no longer needed. By contrast, mobile devices are widely available at a minimal cost and manageable supporting infrastructure investments. In a sense, therefore, FinTech can become a way of saving money in connection with product delivery – doing what you have always done but better and more profitably. Beyond this, it can also serve as a means of economic inclusion and empowerment by bringing new people and business within the realm of formal financial intermediation, thereby increasing the flow of capital and boosting investment. All indicators suggest that there is immense room for improvement in these areas as 42% of the world’s adult population (according to the World Bank) remains excluded from the formal financial system. If FinTech successfully provides the means to overcome these limitations, then the potential opportunities facing the successful innovators as well as the financial companies embracing them must be exceptional.

There is widespread agreement that the objective of Islamic finance is far broader than merely the intermediation of capital in line with particular principles of jurisprudence. Rather, inclusive economic development is commonly seen as integral to the ethos of Islamic finance.

Needless to say, the characteristics of most Muslim-majority economies make this a necessary objective from a variety of other vantage points as well. Because of the low level of development and the limited degree of urbanization in some of the more populous Muslim-majority countries, substantial segments of the population have limited or no access to formal financial intermediation. In other words, the potential clientele of Islamic banks includes a large un- or under-banked population base, which have not been effectively served by the traditional banking model. According to World Bank statistics, four-fifths of the Middle East-North Africa population are unbanked. This is the highest percentage for any region globally. More generally, it is estimated that as many as 72% of the people living in Muslim-majority countries do not participate in formal financial intermediation.

In most cases, this gap is likely due to the cost of formal financial services. Conversely, large segments of the market are not attractive to traditional banks because they cannot be serviced in a cost-effective manner. The experiences of a large number of countries now underscore the exceptional transformative power of FinTech in catering to the needs of this large population base. Mobile banking solutions have proven an effective way of reaching the unbanked in many countries. By pushing out the frontiers of access to finance, FinTech innovations have helped reduce the universe of the unbanked.

Perhaps the best-known example of the inclusive power of FinTech is M-Pesa, which was launched by Vodafone for the leading mobile network operators in Kenya and Tanzania in 2007. It has subsequently expanded to several other jurisdictions, albeit with mixed results. M-Pesa successfully leverages the popularity of mobile phones, which in many emerging economies provided a means of reaching a far greater proportion of the populace than any alternative infrastructure. M-Pesa is a banking service that operates without branches as the accounts are stored on mobile devices and withdrawals of physical money can be made through a network of agents, which tends to be retail outlets. Through M-Pesa, mobile users can deposit, withdraw, and transfer money, as well as make mobile payments for goods and services.

As was noted above, by better-connecting sources of capital with its users, FinTech can also boost entrepreneurship. Even beyond this, crowdfunding can also give access to advisory resources as capital providers seek to make their money work better. Similarly, the ability of disaggregate and decentralize investments through digital technology can enable retail investors to tap new asset classes and diversify their portfolios. For instance, Yielders, the UK’s first Islamic FinTech, provides customers access to the property market with as little as GBP100. Historically, this market would have been effectively closed to many classes of retail investors. Digitization can help in the social financing space by facilitating the collection of zakat and other payments. It can also make it easier to undertake charity fundraising.

Being able to provide financial services safely through these alternative channels is, of course, of the utmost importance since many of the poorer customers have minimal financial safety nets and do not tend to have access to formal risk insurance. Nor is it clear that this can be provided cost-effectively on the scale needed. One of the attractions of mobile payments is the ability to leverage the know-your-customer as well as the risk and security frameworks of mobile operators which need them for their own reliability and reputation.

Again, these benefits are not unique to Islamic finance. However, their relative importance in light of the socio-economic realities of many Muslim-majority countries is indisputable. Moreover, they can become an important growth enabler for existing Islamic financial institutions by allowing them to increase their customer base at home as well as to expand into new markets in more cost-effective ways by establishing new kinds of partnerships.

Customer-centricity to Rejuvenate the Industry

There is a growing consensus among industry that Islamic finance in its “core jurisdictions” (that drove its rise) has entered a new phase of markedly slower development than that observed during its first couple of decades of rapid expansion. There is a widespread sentiment that the initial era of rapid, convergence-style growth is over as the industry has matured and picked most of the “low-hanging fruit” available to it. The somewhat tighter liquidity conditions in the face of lower oil prices may be further contributing to this in the Gulf region. Globally, the pace of growth of Islamic assets is slowing from double-digit figures to around 5%. While Islamic finance is finding new growth opportunities by expanding its geographic footprint, it seems increasingly evident that new thinking is required to enhance or refocus the growth drivers in the GCC and Southeast Asia.

One of the promises of FinTech comes from providing a superior customer experience thanks to greater speed, flexibility, transparency, and reliability. Large segments of personal and corporate customers in the core markets have an obvious affinity for Islamic finance. But Shari’a-compliance is not necessarily the sole or the most important factor motivating their product choice or choice institution. For many of these customers, Islamic finance has often been disadvantaged by its high cost, a narrower product range, the perception of less innovation, and a more traditional culture. Yet there is growing evidence, especially for the tech-savvy younger generations, that convenience, speed, cost, and transparency are at the heart of informing and motivating their choices. Under the circumstances, if Islamic finance wants to fully capitalize on the demographic and cultural trends in these markets, enhanced customer experience is likely to become an increasingly critical success factor. Moreover, greater comparability among financial service providers and products is likely to be a key benefit of FinTech. This will force Shari’a-compliant institutions to strive harder for efficiency and better service. But it is also more likely to reward institutions that do this successfully.

The attraction of FinTech comes in part from the fact that it can put Islamic finance on a level playing field with conventional finance. In crafting new customer experience, Islamic finance need not, in this area, be disadvantaged by its limited products range and smaller, less liquid markets (eg for sukuk). It can fully utilize the same toolkit as other institutions to create a superior customer interface and a service delivery mechanism that is more responsive and timely.

Moreover, through technological innovation, Islamic finance can better harness market data and customer behaviour analytics to refine its service delivery and customer engagement mechanisms on an ongoing basis. It can use market demand to design more relevant

and appropriate solutions. When these become the driver of product and service evolution, Islamic finance can potentially be freed from its reactive paradigm, i.e. the perceived need to respond to competition from conventional institutions. It will also be better able to differentiate between various market segments by better customizing and even personalizing communication.

By taking a lead in defining the parameters of customer experience, Islamic finance can redefine the marketplace through the introduction of new parameters that are of potential relevance for shaping customer choice. Some of these could be market specific. For instance, the GCC countries are all going through a major fiscal overhaul and part of customer interface with banks could come from increasing awareness about potential ways of conserving water and power. Banks could even partner with non-bank service providers that can allow individuals and companies alike to behave in more sustainable ways. More generally, the sustainability agenda is rising in importance and is of particular relevance in economies characterized by extreme aridity and critical reliance on imported food.

In general, Islamic finance can capitalize on FinTech to create a customer interface that goes far beyond the narrow remit of financial products. It can link people’s financial choices to the broader halal economy, which is enjoying growing popularity and attention. By linking finance to other lifestyle issues, Islamic finance can find ways of forging stronger links, especially with younger customers. Other areas where FinTech has a potentially powerful role to play include financial education and financial planning. All of this could help create more customized, fulfilling, and enduring customer relationships.

An Emerging Ecosystem

As of the end of 2017, there were an estimated 120 Islamic FinTech companies around the world. All of these entities either have or are in the process of obtaining Shari’a certification with the objective of catering to the significant and growing needs of the world’s 1.7 billion Muslims. The geographic footprint of these companies is diverse and while many are based in the core jurisdictions of Islamic finance, a significant proportion operate from the established FinTech hobs of the West, albeit typically with objective of servicing also Muslim-majority jurisdictions.

While the initial growth impetus to Islamic FinTech was largely market-led and probably came from the general confluence of FinTech and the potential of Islamic finance, this market segment is now gaining broader recognition. The perceived potential of FinTech in Muslim-majority countries has triggered a major paradigm shift in attitudes among regulators, intermediaries, and end users alike. While these initiatives do not necessarily have a direct link to Shari’a-compliant finance, it is only logical that there should be interest in marrying these new technology trends with Islamic finance, which is a systematically significant element of the financial sectors in the Gulf and in Malaysia. To an extent, the development of Islamic Fin- Tech can be expected to benefit indirectly from there broader efforts to foster the development of FinTech.

Indeed, the initial steps toward FinTech in Malaysia and the Gulf alike were largely agnostic. New providers emerged, especially in the area of payments solutions, while existing mid-office and technology operators developed a new interest in FinTech solutions. A growing number of companies have devised digital wallets and other solutions to speed the deliver and increase the reach of financial services. Indeed, for instance the number of FinTech start-ups in the Middle East-North Africa region has increased from less than 20 in 2010 to more than 100 today.

As the global FinTech ecosystem expands its footprint, Islamic financial institutions can benefit from it, albeit in ways that are broadly identical to those available to a conventional institution. Indeed, an element of this narrative risks being essentially reactive, replicating many of the challenges that Islamic finance as a whole has been criticized of. This is likely to be primarily a story of localizing FinTech solutions for Muslim-majority jurisdictions. Of course, in practice, this may contribute to the greater reach and cost-effectiveness of Islamic finance. However, there are a growing number of instances where change within Islamic finance is the sole focus of new FinTech-related initiatives. Indeed, such “Islamic FinTech” seems to be increasing in popularity and is increasingly seen as an industry sub-segment in its own right.

In practice, the rise of Islamic FinTech is likely to be shaped by the concurrent trends of Shari’a-inspired innovation and the creative adoption and adaptation of more general FinTech innovations. In either case, the core countries of Islamic finance now seem to be ready for this paradigm shift. For one thing, the initial conditions in many Muslim-majority countries are favorable with internationally high mobile and internet penetration rates, which are continuing to go up at a rapid pace. These indicators stand at 141% and 81%, respectively, for instance in Malaysia. Across the Gulf region, both indicators are among the highest in the world.

Key Islamic FinTech Development Across Jurisdictions

Similarly, the policy impetus behind FinTech is increasingly strong. In all these “core jurisdictions” of Islamic finance, regulatory institutions have embraced FinTech. The Securities Commission in Malaysia introduced crowdfunding guidelines in February 2017 and regulations for P2P financing in April 2017. The first participants in the regulatory sandbox were approved in June 2017. In January 2017, Dubai International Financial Center (DIFC) launched a FinTech accelerator called FinTech Hive. Supported by Accenture, the accelerator aims to transforming DIFC into a global FinTech innovation hub and empower entrepreneurs to innovate. In May of the same year, Dubai Financial Services Authority (DFSA) launched the Innovation Testing License for Fintech firms, which allows qualifying FinTech firms to develop and test innovative concepts from within the DIFC without being subject to all the regulatory requirements that normally apply to regulated firms. Bahrain, similarly, has seen a number of important new initiatives in the course of 2017 to proactively drive the development of this emerging industry forward. The Central Bank of Bahrain (CBB) issued regulations for a FinTech sandbox and created a dedicated unit to supervise the emerging FinTech industry. Both the DFSA and the CBB have launched crowdfunding regulations to open up an important new source of funding for technology-based start-ups.

DIGITAL IN THE MIDDLE EAST

KEY STATISTICAL INDICATOR FOR THE REGION’S INTERNET, MOBILE, AND SOCIAL MEDIA USERS

The Bahrain Economic Development Board announced plans to host the first physical FinTech cluster in the Kingdom, making it the largest dedicated FinTech cluster in the region. DFSA and Securities Commission Malaysia are collaborating in the area of FinTech innovation.

In an important step for Islamic finance, Shari’a-compliant institutions themselves are increasingly beginning to embrace FinTech thanks to its potential to better serve their customer base. This marks an important and welcome change from a pattern where Islamic financial institutions have not tended to be at the forefront of developing FinTech solutions. Recent initiatives in the GCC attest to this change of heart. Abu Dhabi Islamic Bank has teamed up with Abu Dhabi Global Market to promote the growth and development of the FinTech ecosystem in Abu Dhabi as well as the UAE. Both parties will also seek to develop local fintech entrepreneurship through mentorship and knowledge transfer across incubation, accelerator, academic and internship programmes.

In another development, Abu Dhabi Global Market and the Responsible Finance & investment Foundation have entered into a partnership to bolster the growth and sustainability of the FinTech ecosystem through financial inclusion and ethical and responsible finance practices. Similarly in Bahrain, a partnership between Al Baraka Banking Group, Ithmaar Bank, and Bah- rain Development Bank was announced in early December. ALGO Bahrain is the first-ever FinTech consortium of Islamic banks globally and has set itself the goal of launching 15 FinTech platforms by 2022. In Malaysia, the Malaysian Digital Economy Corporation is developing the country’s first Islamic Digital Economy (IDE) framework aimed at increasing the gross domestic product (GDP) of the digital economy segment to 20% by 2020. The framework will focus on start-ups and venture capital players to ensure that these businesses are Shari’a-compliant before providing them with the halal certification.

Potential Challenges

While the potential of FinTech to drive the development of Islamic finance to a new level seems exceptional, progress is likely to involve some challenges. Embracing new technologies will involve disruptions and difficulties, whether because of poor awareness and education or new vulnerabilities to cybercrime. The political fallout from such challenges in many cases risks triggering a regulatory response. Perhaps problematically from the perspective of the dynamic, disruptive nature of FinTech; regulation is an inherently a reactive force. It adapts to new market realities and often is not in a position to make an informed judgment on any innovation before the impact of that innovation – positive or negative – is known.

It is not without reason that regulators are often accused of fighting old battles. This naturally creates potential risks of regulatory overreaction in some areas. This risk has been reduced, but by no means eliminated, by the willingness of a growing number of regulators to provide sandboxes where new ideas can be both trialed and observed before they are brought to market. In practice, however, FinTech is unlikely to be easy to regulate, given its accelerating ability to morph. Nor is it clear that regulation is the right tool for managing growth and evolution of this market segment. It may continue to be more efficient to maintain the regulatory focus on products and intermediaries, except perhaps in instances where new technologies can entail risks because of a lack of market awareness or understanding. Yet making the right determination is likely to prove challenging.

Islamic FinTech may well face its own challenges in terms of ensuring Shari’a compliance as well, largely due to its ability and tendency to evolve rapidly. How do we make sure that a revised version of solution that received a fatwa is also Shari’a-compliant? How often, how and by whom should that determination be made if the integrity of the sector is to be preserved without compromising its economic impact.

While the answers to these questions are likely to remain work in progress for many years, it is more obvious that Islamic FinTech is the reality of today and possesses not only extraordinary growth potential but also the promise to reshape the broader Islamic finance sector. Whatever the challenges ahead, this may offer unprecedented opportunities to grow and rejuvenate Islamic finance is ways that will ultimately enable it to better realize its aspirations.