Introduction

In finance, ethics often refers to including moral values in financial decisions. In the wake of the financial crisis that started in 2007 and the resulting loss of trust in the financial sector, ethics in finance is experiencing a renewed focus. This Chapter attempts to compare the approaches to ethics in contemporary Islamic and secular ethical finance. It is confined to those practices by financial institutions that are desirable but may not be required by law.

Ethics in Islamic finance

Anecdotal evidence suggests that people seem to associate a range of things with ethics in Islamic finance, from the minimum juristic requirements to the aspirational— avoiding sin industries (e.g., alcohol), abiding by the two core prohibitions of riba and excessive gharar, using equity and discouraging debt, promoting economic justice, widening access to finance, enhancing human welfare, caring about the environment, and so on.

Some may argue that the two core prohibitions provide the foundation for wider ethics in Islamic finance: The prohibition of riba seeks to avoid making money from money and promotes asset and enterprise; the prohibition of excessive gharar seeks to avoid speculative excesses and promotes risk-sharing; and together, the two should keep finance tied to the real economy.

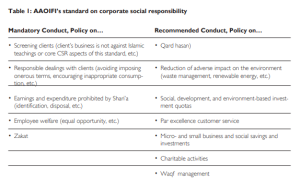

It is difficult to separate “ethics” from “social responsibility” and “sustainability”; these are different labels often put on similar ideas, and the fine distinctions made are not widely shared. Beyond the core prohibitions, much of what may be considered as ethical in Islamic finance is covered in the standard “Corporate Social Responsibility Conduct and Disclosure for IFI” by the Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI).

Table 1 gives a top-level view of the AAOIFI standard, which covers mandatory and recommended conduct. The standard states that it is based on Islamic ideas, such as that man is the vicegerent of and accountable to God.

Ethics in secular ethical finance

In the secular space, ethics tends to revolve around an environmental, social, or corporate governance (ESG) issue. A useful illustration of this approach is shown by the U.K.-focused website www.YourEthicalMoney.org, a non-profit initiative of the EIRIS Foundation.

Among other things, the website shows where a U.K. bank stands on a three-point scale (worse, OK, better) using the criteria shown in Table 2. The highest-rated bank fared “better” on all except responsible lending, on which it was rated OK, with 10 percent women directors an Islamic bank got “better” on the first two, OK on financial exclusion, and “worse” on others, with 27 per- cent senior management positions held by women; and the lowest-rated entity was “worse” on the first seven criteria and had no data on women on the board.

Similarities and differences

Not everyone may agree that AAOIFI’s standard or YourEthicalMoney’s criteria are accurate representations of approaches to ethics in finance. Nonetheless, the two are representative of the current thinking in their spheres and help us compare the two approaches. The main similarity is that both Islamic finance and secular ethical finance focus on the purpose of financing and the financier’s actions to avoid harm and do good to society and the environment.

There are differences as well. Within the ESG focus, the AAOIFI standard puts more emphasis on society, whereas YourEthicalMoney’s criteria put more emphasis on the environment. More importantly, because of the two core prohibitions in addition to the purpose of financing, Islamic finance is concerned with the structure of financing, which does not stand out as an ethical concern in the secular space.

In the secular space, the source of ethics is the people. The phrase “What is ethical depends on you” means that ethics could change across place and time. People may be sensitive to one issue but not another, and financial institutions may target specific issues, such as environmental sustainability.

That may not be true to the same degree in Islamic finance, where the source of ethics is the religion; it is the interpretation and not the source that changes and an Islamic financial institution has to take the given ethics as a whole. For instance, in general, an Islamic equity fund has to screen out all sin industries (from alcohol to conventional banking), avoid highly leveraged companies, and donate tainted dividend income, whereas a secular fund may hold itself out as ethical by only excluding tobacco.

On the whole, Islamic finance seems to put more ethical constraints on financing than secular ethical finance does, although critics may argue that the Islamic finance industry respects these constraints more in form than in substance.

Ethical finance—A lesson from the United Kingdom

The available data suggest that ethical finance in the re- tail market in the United Kingdom is growing. Accord- ing to the Ethical Consumerism Report 2010¹ from the Cooperative Financial Services group, which includes the Co-operative Bank, “Ethical finance increased by 23 per cent to reach £19.3 billion between 2007 and 2009, helped by a ‘flight to trust’ among consumers dis- enchanted with much of the financial services sector”². Earlier, the Cooperative Financial Services group also re- ported that in spite of the financial crisis, 2009 was the “third successive year of double-digit growth in Group sales and profit,” and in its 2009 financial statements the Co-operative Bank reported that switching of customer accounts from the so-called ‘big five’ banks to the Co-operative Bank increased significantly.

Table 2: Criteria Used for Evaluating Banks by YourEthicalMoney.org

- Green/ethical products (e.g., green mortgages)

- Ethical lending or insurance (e.g., screening clients on human rights)

- Responsible lending (e.g., checking on borrower’s ability to pay)

- Financial exclusion (e.g., no-frills bank accounts for low-income individuals)

- Environment (e.g., energy and waste management)

- Carbon neutral (e.g., offsetting emissions)

- Equal opportunities (e.g., race and gender in employment)

- Percentage of women on board of directors or in senior management

This growth is in sharp contrast to Islamic finance, where attention is often drawn to the persistent losses of the Islamic Bank of Britain or the discontinuation of the business of Salam Insurance. Contrary to the growth prospects of ethical finance, the growth prospects of Islamic finance in the retail market in the United Kingdom are frequently questioned.

Perhaps a lesson that can be drawn from this experience in the United Kingdom is that unless a meaningful ethical proposition can be effectively communicated to customers at large, the economic benefits of pursuing ethics can be hard to realize.

Expectations gap in Islamic finance

In practice, other than refusing to finance “sin” industries, ethical expectations triggered by branding services as “Islamic” are proving hard to meet. Despite the expectation of profit sharing, most of the financing in the Islamic financial sector is debt-based, in which the form of financing is changed to that of a sale or a lease without necessarily changing its economic substance. For example, payment schedules and terms and conditions in home financing in the Islamic financial sector may look very similar to, if not the same, those in a conventional mortgage.

Customers are usually told that the difference between Islamic finance and conventional finance lies in fulfilling certain technical conditions of classic Islamic commercial jurisprudence that give financing the form of a trade or a lease. Some customers scale down their expectations and take what is available; others turn away in disappointment.

The issue here is that reliance on financial structures that in their economic substance are interest-bearing debt does not fit with the discussions on economic justice in the Islamic finance literature, which often identify interest-bearing debt as a cause of economic injustice. If the “Islamic” in Islamic finance is confined to changing the form of financing, it may be difficult to convince people of its very reason for existence.

Expectations gap in socially responsible investing

The gap between ethical expectations and practice is not unique to Islamic finance. Other shades of ethical finance, such as socially responsible investing (SRI), face it too. One would think that because lending money on interest is not an issue in SRI, meeting expectations would be easy. Not exactly.

In 2004, in a research paper titled “Socially Responsible Investing4,” Paul Hawken found that the cumulative investment portfolio of the combined SRI mutual funds is virtually no different than the combined portfolio of conventional mutual funds. In other words, the expected ethical difference was blurred. Interestingly, Hawken also noted in 2004 that “Muslim investors may be puzzled to find Halliburton on the Dow Jones Islamic Index fund. In its 2007 “Guide to Climate Change Investment,” Holden & Partners provided a similar finding: SRI and ethical funds perform just as well (if not slightly better) than their mainstream counterparts because in most cases they are in fact mainstream.

Ethics vs. profits

A key argument made against the pursuit of social and environmental goals in both Islamic and secular ethical finance is that the job of for-profit financial institutions is to maximize profit for their shareholders and that profit-able business leads to a prosperous society. If shareholders want to do something good for society and the environment, they can do so in their private lives. This argument is often traced to Milton Friedman and his New York Times Magazine column published in 1970, “The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits5.”

Those who disagree with this line of reasoning point out that Friedman also qualified his position by saying that the “responsibility [of a corporate executive as an agent of shareholders] is to conduct the business in accordance with their desires, which generally will be to make as much money as possible while conforming to their basic rules of the society, both those embodied in law and those embodied in ethical custom.” One can argue that today if the ethical custom of society requires to avoid- ing harm and doing good to society and the environment, then the corporate executive ignores the same in his decisions.

A more frequent argument in favour of bringing ethics into practice is that finance does not exist in a vacuum, and as a result, it can create significant negative externalities—or costs—for the real sector, as observed in the financial crisis. Taxpayers’ money has been used to save troubled financial institutions, the actions of which are held to have created widespread hardship in society. There is no denying that externalities exist in the financial sector, and by definition, externalities are a market failure; therefore, relying on “free markets” to address externalities is unlikely to work.

The financial crisis has encouraged a rethinking of the idea that the sole job of management of a company is to maximize profits for shareholders. In March 2009, the Financial Times reported that Jack Welch, former CEO of General Electric, who is often thought of as a proponent of shareholder value, said, “On the face of it, shareholder value is the dumbest idea in the world.” Soon afterwards, in a Q&A session with Business- week, Jack Welch elaborated that his remark was not a new position for him. Nonetheless, the widespread debate generated by the reported remark shows that the consequences of a financial crisis have weakened the idea that the sole job of the management of a company is to maximize profits for its shareholders.

The need for ethical customers

In the debate on ethics versus profits, an argument in Islamic finance and secular ethical finance is those financial institutions using the “Islamic”, “Ethical”, or “Sustainable” label should earn their profits while actively doing something positive because that is what the stakeholders expect from these labels.

For example, Islamic banking should focus on small and medium-sized enterprises rather than high-net-worth individuals; Islamic financing for cars should finance fuel-efficient vehicles, such as hybrids, instead of fancy gas guzzlers; and Islamic project financing should push for fair treatment of construction workers and efficiencies in energy, waste, water, and carbon.

The catch here is that for such positive pursuits to work, customers also have to do their part. That is, for the financier to lease a hybrid vehicle, the customer also has to want one. To avoid interest-bearing debt in the financing, customers have to be ready to share profits with the financier, and to make investments rather than extend interest-bearing loans, customers should probably seek equity funds and not bank accounts.

Similarly, if customers want Islamic finance to pursue socioeconomic goals, they should be willing to share any additional risks and costs. If customers are unwilling to put their money where their heart is, then finance, pragmatic as it is, may also be unwilling to go very far in non-financial pursuits.

Difficult choices in ethical finance

Ethical issues are often not black and white; there are competing choices with associated costs and benefits as well as a need for debate, and decision-makers need to choose how far they should go to honour their commitment to ethics. Consider, for instance, an investment adviser advising individual investors who wish to invest ethically. News breaks out that a company in the clients’ portfolio is involved in a controversial practice, and the clients expect some information and advice from the adviser. Should he advise the clients to wait until the facts can be established and the company has had a chance to react? Should he advise engaging with the management of the company to change the company for the better? Should he advise selling the shares to disassociate from the controversial company? Should he advise doing nothing because the size of shareholding is insignificant and other companies in the sector may face similar controversies? Should he advise leaving any action to the concerned regulator and buying more shares because a drop in the price after the news breakout may have created a profitable opportunity?

In many cases in ethical finance, there is no one right answer. However, that is not to say there should be no debate or action. There are examples of investors working their way through difficult issues and making bold decisions, such as the exclusionary screening used by the large Norwegian sovereign wealth fund for companies producing controversial weapons and tobacco.

Ethical finance and mutuals

A mutual legal structure has long been used in ethical finance. For example, Scottish Widows was founded as a mutual life office in 1815 and it remained a mutual till it demutualised and became a part of the Lloyds Group in 2000. Mutuality, in general, is seen as more amenable to ethical pursuits in financial services: It is not subject to the dichotomy between shareholders and customers; one membership means one vote; and the entity may not single-mindedly pursue a one-point agenda of profit maximization under the watchful eyes of the stock market. A not-for-profit mutual structure may also help allay the fears of those who see modern Islamic finance as Shari’a arbitrage, where in the name of religion, Muslims are asked to pay more to for-profit companies for something that is otherwise available for less.

Mutuality has not been the structure of choice in Islamic finance except in establishing takaful funds, which, again, are usually managed by a for-profit shareholder-owned operating company. Professor El-Gamal, known for his criticism of the modern Islamic finance industry’s putting religious form over substance, has also advocated mutuality on religious, economic, and regulatory grounds. This is not to say that mutuality by itself can overcome all challenges. For instance, mutual or not, the organization would need to offer service standards that meet the expectations of its customers.

Mutuality may also bring challenges of its own in terms of accessing capital, particularly in the initial years. Mutuals have dwindled in numbers after a wave of demutualization. It remains to be seen whether, in this era of globalization, large financial institutions, and complex regulatory requirements, new true-blue mutuals can be successfully created for ethical finance.

Conclusion

A comparison of ethical approaches in contemporary Islamic and secular ethical finance shows significant similarities and differences between the two. In both Islamic and secular ethical finance, pursuing profits while pursuing ethics in for-profit limited liability companies remains a divisive issue. The main challenge that faces both Islamic finance and secular ethical finance, however, is the gap that is often observed between expectations that are created by using such labels as “ethical,” “Islamic,” “sustainable,” and “responsible” and the actual practice.